KEITH Dean is a legend of the customising scene in the US, and is the go-to man if you want a chop-top just like Barris Kustoms would have done it back in the day. He has also worked on countless movie cars dating right back to the late 60s and is a specialist in recreating some of the most iconic vehicles seen on the screen.

Born in Detroit but a resident of California since he was a few months old, Keith will be Down Under for the first time this weekend as part of Meguiar’s MotorEx.

What are your plans while you’re at MotorEx, Keith?

What I’ve been doing here in the States is an apprenticeship chop-top clinic, so with Owen Webb’s help we’ve been putting together a clinic [for MotorEx], and we’ll find some youngsters to participate.

What kind of car will you be chopping?

A ’32 Ford pick-up. I’ve got to figure out how to take my time so I don’t get it done too quick; I’ve chopped those during a lunchtime! What I hope to do is show them a little bit more of why we do this rather than just the physics of doing it.

Your dad Dick started South End Kustom in 1956 and has worked with some of the biggest names in customising, and you’ve always been around it. How have you seen customising progress over the years?

Your dad Dick started South End Kustom in 1956 and has worked with some of the biggest names in customising, and you’ve always been around it. How have you seen customising progress over the years?

Because my dad was so much involved in every little aspect of car building – a race car, a show car, a TV car, he was involved in a lot of different fields – we saw it from a different perspective. Back in the 60s, customs were dead, muscle cars were coming up and it was the lowriders that kept customising going. In the early 70s it started coming back; probably the Happy Days TV show and American Graffiti film brought it back.

What was your dad’s specialty?

What was your dad’s specialty?

My dad was known for just getting it done. He was one of the best metal fabricators in Southern California. It’s a little-known fact that the AC Cobra wouldn’t have looked like it did if it wasn’t for my dad; he was the one that shaped the body. When it came in as the AC Ace, Carroll Shelby hated it; it was flat in the nose, no flares or anything like that, so he hired my dad to work at Dean Moon’s.

So he worked on pretty much anything?

He had six kids, so he was hustling all the time. He would build dragsters in our garage on the weekends so he could have enough money to go out and play. He made a couple of land speed cars as well [Goldenrod and Mickey Thompson’s Challenger]; his range was far and wide. He even had a stint with Mattel when they were starting out and he worked with them developing toy products.

What kind of stuff did he do with Mattel?

What kind of stuff did he do with Mattel?

I was pretty young when that was going on, but he would tell me that they would just sit around and come up with dumb ideas and then try and make them work. My dad took my older brother’s tricycle, cut it and reshaped it and made it rear-steer with a joystick and took it to Mattel. They made the V-RROOM X-15 out of it [Google it – it’s wild!].

Where did you get the ‘Kid’ nickname?

Where did you get the ‘Kid’ nickname?

Dean Jeffries said – because Dean was always called The Kid too – don’t let them call you Kid, because you’ll be 60 years old and they’ll still call you Kid. Here I am, 60 years old and the name has stuck [laughs]. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Dennis the Menace? Well, that was me. When I would ride down the street on my tricycle, people would shut their garages because they knew if I got in there I would find something to destroy. The same thing happened when my dad took me to the workshops. I’d get pulled by my ear over to my dad and they’d say: “Is this your kid, Dean?” So it progressed from there.

When did you first start working with your dad?

When did you first start working with your dad?

I was relentless, and he just gave in. I was probably eight or nine and my dad had a dune buggy shop called Shalako and since I was in school during the week, on the weekends he’d bring me in and show me how to do fibreglass and lay-ups and do the small parts. He got a couple of movie jobs and I asked if I could help make some props for the movie cars, so I worked on Death Race 2000 and Diamonds Are Forever, and then later on with George Barris I worked on a couple of TV shows and movie cars with him.

You still had to go to school, though?

You still had to go to school, though?

Yes, I had to finish school, so I graduated in ’77 and he sent me off. He said: “You gotta go get a job before you work for me, because you gotta know what discipline is.” So I worked for Disneyland for a year or two and came back. He had a huge shop, and because all the other workers were rumbling that the kid’s going to come in and take over, the first thing my dad did, right in front of everybody, was hand me a broom and say: “There’s 10,000 square feet, don’t screw it up.” That was the first job I had as an adult.

You’ve done some work on some big-name customs since then, so you eventually learnt all the cool stuff, like how to chop cars.

You’ve done some work on some big-name customs since then, so you eventually learnt all the cool stuff, like how to chop cars.

My dad was known for cutting Mercurys; he would cut anything, but Mercurys were what he was known for. There were a couple of them, people say, that to this day are the best Mercurys ever done. When my dad first came out here to work for George Barris, Sam [Barris] was still with him, and Sam didn’t teach too many people too much of anything, but he liked my dad so he took him in and showed him how he cut his Mercurys. So that’s what he taught me, and that’s about as old-school as you can get.

So tell us, what is the secret to chopping a car?

So tell us, what is the secret to chopping a car?

I like to look at the profile and not see a dip in the roof. What I do is pie-slice up through the radiuses and weld it back together; that’s the way that Sam would do it and the way my dad would do it. We like to keep the catwalk – the panel behind the rear window – real short and just get the car to stretch out. Most guys think it’s too much work on the roof so they just push the roof forward and make the catwalk longer.

Do you still weld with an oxy-acetylene torch?

We tack with a TIG to hold everything in place, but I stick to the old traditional oxy-acetylene because it fuses the metal together, it tempers it and I can beat it around and nothing cracks.

Do you work off renderings at all?

Do you work off renderings at all?

The ones that come out best are the ones that are in my head. Sometimes a customer will come in and ask me to draw up something, so I’ll sketch it up so at least they can go home and show their wives so they don’t get killed for spending all that money. I have a pretty good idea of what the car’s going to look like, but I always leave open doors. I don’t say: “It’s gotta be this way”, because the car morphs as you build it and you have to be able to roll with that in order to get the car to its full potential.

I guess years of experience helps when it comes to making those design decisions?

I guess years of experience helps when it comes to making those design decisions?

My dad actually went to Pasadena ArtCenter College of Design, but he was only there six months before he got drafted during the Korean War. He learnt a lot and he brought that with him when he was teaching me – what to look for, proportioning with cars, why production cars don’t look like prototype cars.

You’ve customised a whole bunch of cars, even a VW squareback, but what are your favourites to work with?

To me, the 40s and 50s cars look more romantic. I built a ’40 Mercury the other day and it looked like the glamorous 50s when a movie star would hop in his car and shoot down the coast highway. If you do it with a 60s car it has to be a muscle car, which is great, I love them, but it’s just a different look and feel.

How many of you work in the shop, and what’s in the build now?

How many of you work in the shop, and what’s in the build now?

There’s myself and one other guy that’s been with me for about six years now, Jess Shepherd. He does mechanical work and some fabrication. I do replica old movie cars for museums and personal collectors, so I’ve got the Joker car from Batman ’66 and the ‘dream car’ version of Greased Lightning. I’m finishing up one of the last original Green Hornet cars and there’s six Mercurys and a couple of Chevys. Fifties-style customs and chop-tops are still real big.

Do you just do the customising or the full build?

What guys do is, they’ll say: “All I want is a chop, then I’m going to take it home.” Then once it’s in the shop they say: “Well, since I’m here, do you think you can do a chassis change and change the motor and shave the door handles?” So that’s usually the status quo.

What are you most looking forward to with your visit to Australia?

What are you most looking forward to with your visit to Australia?

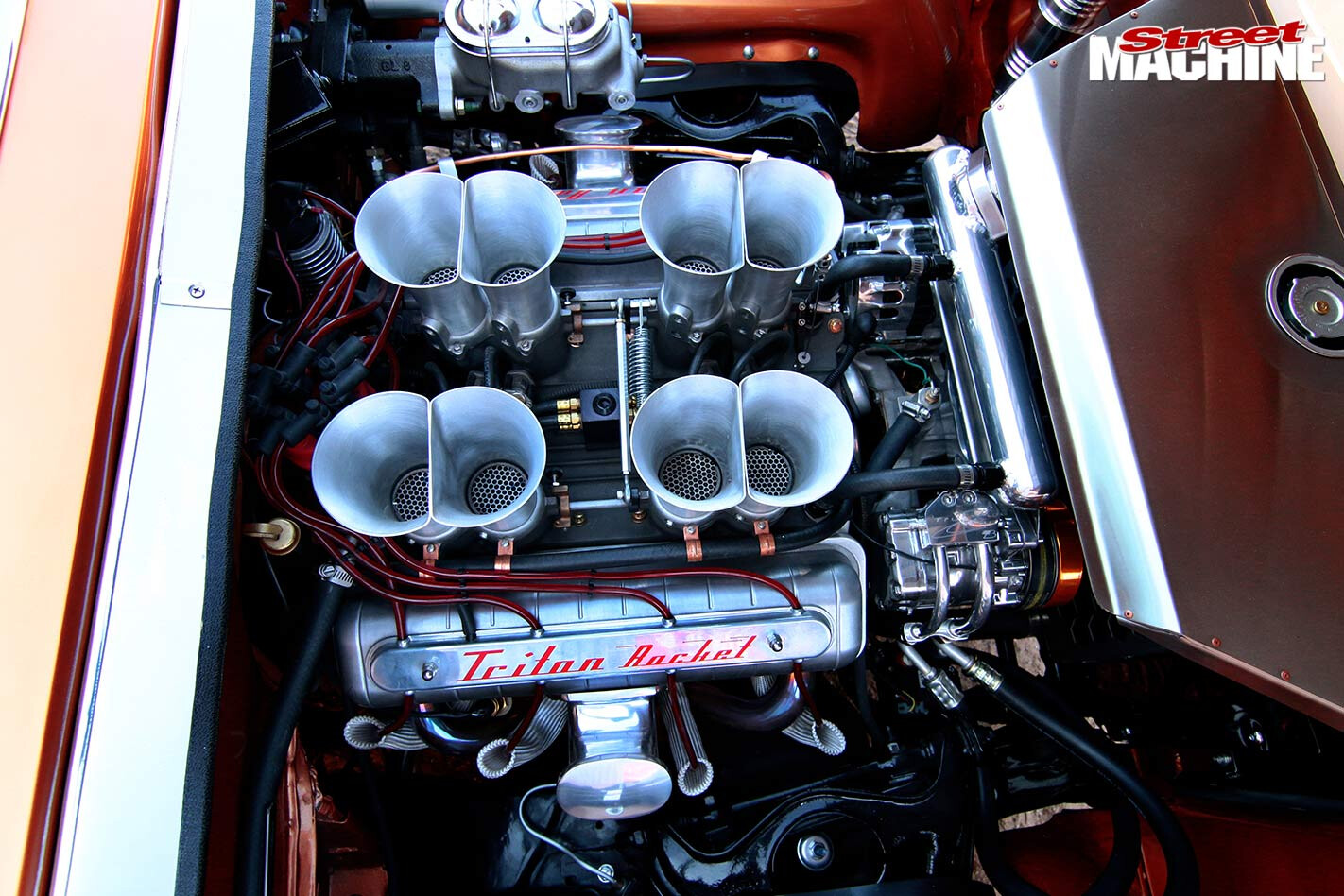

What I’m most excited about is seeing the quality of work you guys do; it’s unbelievable. Pulling a car apart and scrubbing every square inch of it; I do as much as I can, but it’s not what the customer wants and it’s not what I have to do to make a living. I look at the stuff coming out of Australia and I don’t know how you guys do it! From the pictures I’ve seen, it seems you have a lot of high-horsepower, huge motors in things they probably shouldn’t be in [laughs].

Do you always work in a white shirt and tie?

Do you always work in a white shirt and tie?

Bill Hines – we all called him Uncle Bill because we all came from Michigan – he was always in a white shirt. It got me thinking, I need to stand out a little bit more, so I started wearing a shirt and tie. It was to show that I’m a professional and I’m not scared to get dirty.

You must go through a few of them?

I just buy them off the rack, throw them on, then use them for one day. It’s always fun when you light them on fire or something like that.

Comments