IN RECENT years, metal shaping has been referred to by some as ‘a dying art’. The truth is, it’s more alive than ever. Here we’re going to focus on the use of the English wheel to shape metal. Although in just the one article, we can only scratch the surface, so this won’t be a comprehensive ‘how-to’. Instead, we’ll just concentrate on one aspect of using this seemingly mystical bit of gear: planishing.

The point of planishing is to smooth out lumps and bumps in a piece of metal without stretching it. To get to this point we will also brush over two very basic methods of stretching and shrinking.

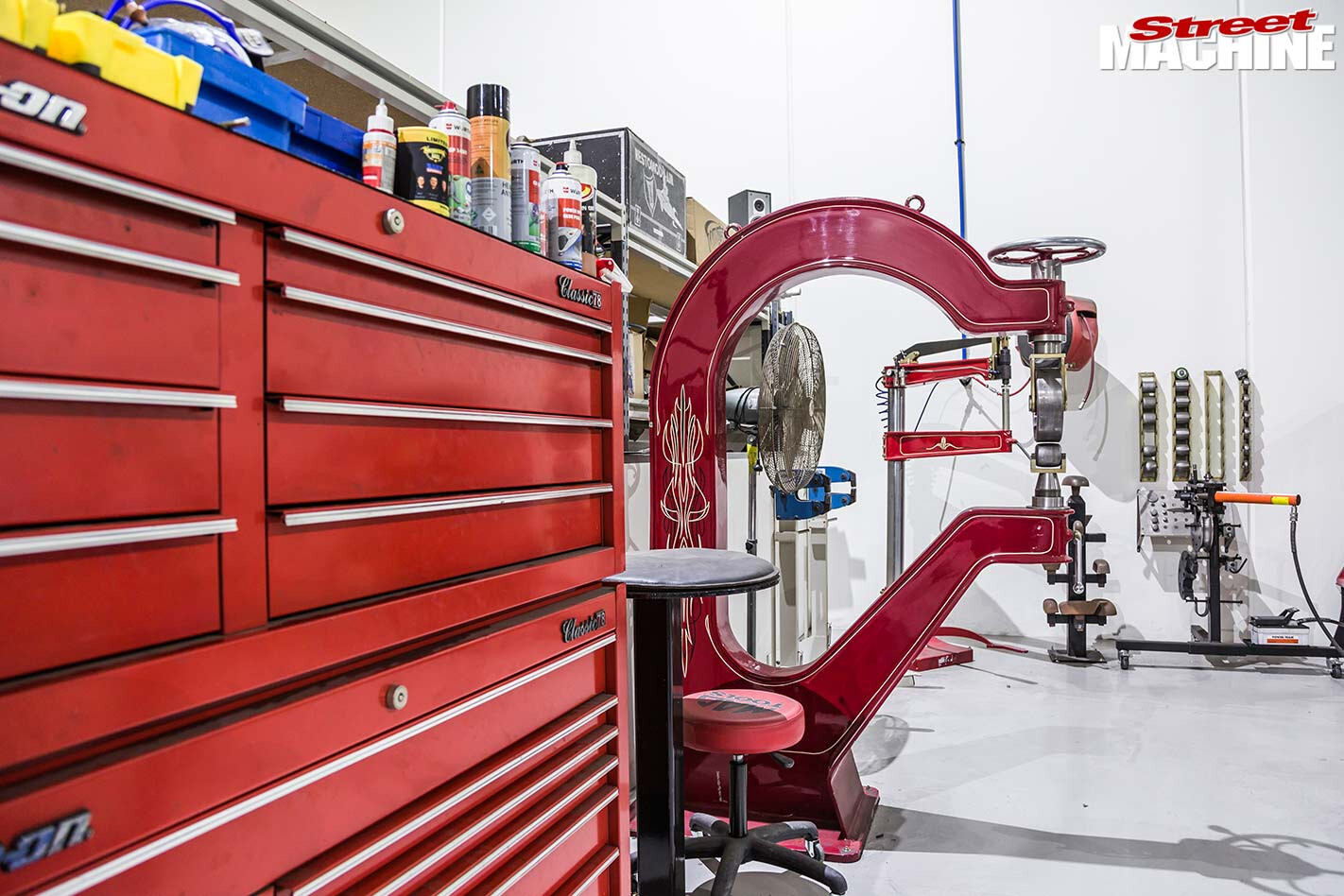

First up, let’s talk about the wheeling machine itself. Unfortunately, a vintage old-school wheel is not something readily available in Australia. But you can get an entry-level wheel for around $500-$700, and with a few easy mods, the performance of these machines can be enhanced in no time. Or if you have a bit more cash to splash, there are some killer American-made workshop/trade wheels like the Baileigh range for around $9000.

First up, let’s talk about the wheeling machine itself. Unfortunately, a vintage old-school wheel is not something readily available in Australia. But you can get an entry-level wheel for around $500-$700, and with a few easy mods, the performance of these machines can be enhanced in no time. Or if you have a bit more cash to splash, there are some killer American-made workshop/trade wheels like the Baileigh range for around $9000.

STEP-BY-STEP:

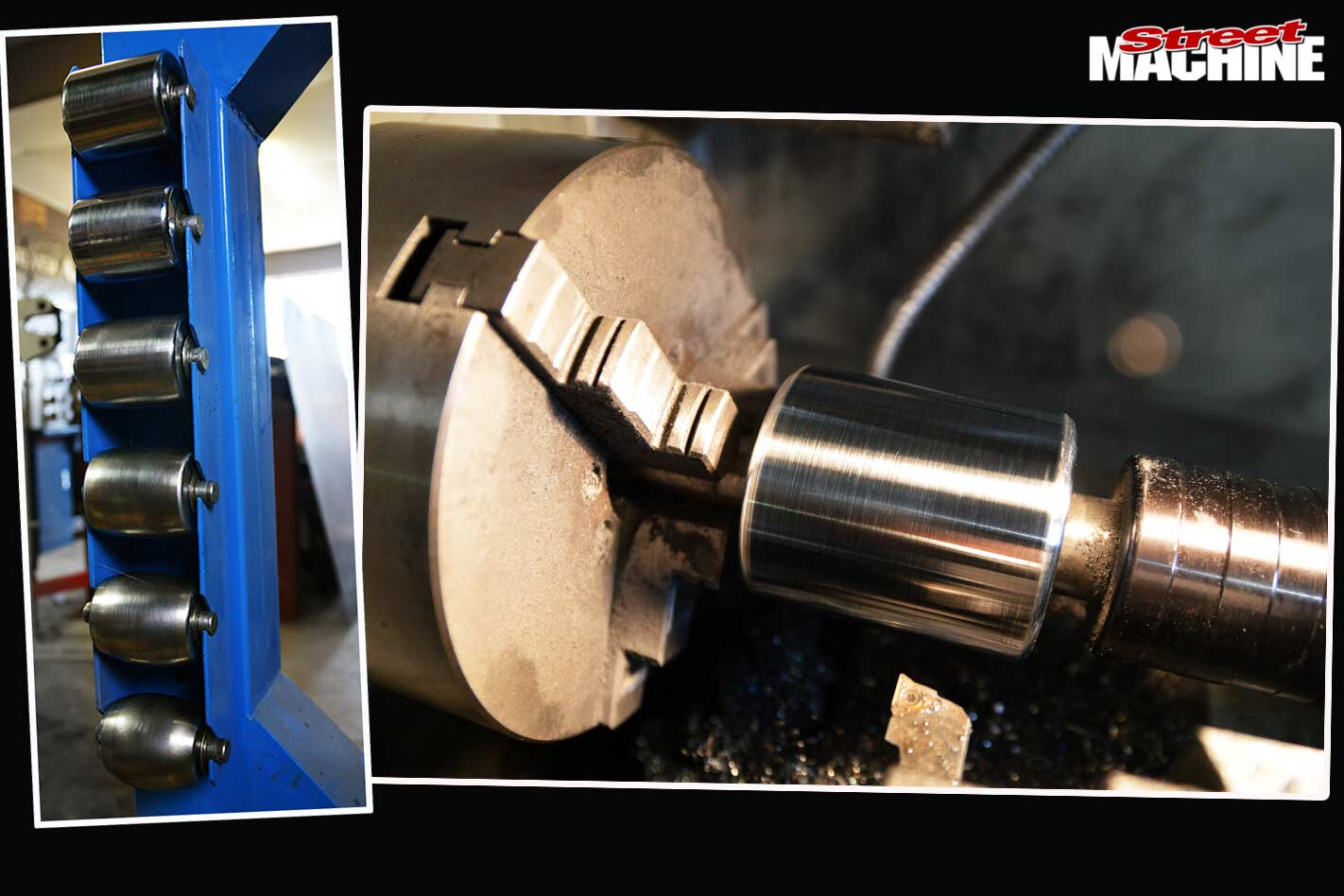

STEP 1. Machining the anvils (lower wheels) of an entry-level machine is a good idea in order to get the best results from your work. A quick smooth-over to take out the ridges is all it takes. Each anvil from one to six has a progressively more pronounced curvature, to help you achieve more crown in your panel

STEP 1. Machining the anvils (lower wheels) of an entry-level machine is a good idea in order to get the best results from your work. A quick smooth-over to take out the ridges is all it takes. Each anvil from one to six has a progressively more pronounced curvature, to help you achieve more crown in your panel

STEP 2. The top wheel is also in need of some machine work, and should be flat. The alignment between the top wheel and the anvil is super-important to get maximum efficiency from the wheeling machine. The more rigid the wheel frame is, the more efficiently it will work, so welding up any play and adding bracing is a good idea. Adding thinner shims to free up the top wheel and help it spin freely may also be necessary

STEP 2. The top wheel is also in need of some machine work, and should be flat. The alignment between the top wheel and the anvil is super-important to get maximum efficiency from the wheeling machine. The more rigid the wheel frame is, the more efficiently it will work, so welding up any play and adding bracing is a good idea. Adding thinner shims to free up the top wheel and help it spin freely may also be necessary

STEP 3. Now the wheel itself is in useable order, we can get to work. A piece of 1mm sheet is marked out with an outer border, or frame, that can be used to help control the inner piece of metal. Shrinking the edges will help achieve a higher crown, while stretching the frame will flatten it back out

STEP 3. Now the wheel itself is in useable order, we can get to work. A piece of 1mm sheet is marked out with an outer border, or frame, that can be used to help control the inner piece of metal. Shrinking the edges will help achieve a higher crown, while stretching the frame will flatten it back out

STEP 4. After manually stretching out the sheet using a mallet and shot bag, things can sometimes look unsalvageable, but that’s not the case

STEP 4. After manually stretching out the sheet using a mallet and shot bag, things can sometimes look unsalvageable, but that’s not the case

STEP 5. As you can see, the edge of the sheet is starting to form a wave. This is good; this is the area that will need shrinking. Put simply, shrinking is basically condensing or bunching the metal together, and can be achieved in numerous ways

STEP 5. As you can see, the edge of the sheet is starting to form a wave. This is good; this is the area that will need shrinking. Put simply, shrinking is basically condensing or bunching the metal together, and can be achieved in numerous ways

STEP 6. As the ‘waves’ get closer together they will start to look smaller and tighter; these are commonly known as tucks. It’s now time to lock the tuck into place by knocking the opened end down

STEP 6. As the ‘waves’ get closer together they will start to look smaller and tighter; these are commonly known as tucks. It’s now time to lock the tuck into place by knocking the opened end down

STEP 7. After a few passes through the English wheel using low pressure to planish the piece, everything starts to smooth out once again. The process of running the piece back and forth, in a tight M-like pattern, can take a little while to master. Be sure to match the contour of the anvil to the piece you are working on

STEP 7. After a few passes through the English wheel using low pressure to planish the piece, everything starts to smooth out once again. The process of running the piece back and forth, in a tight M-like pattern, can take a little while to master. Be sure to match the contour of the anvil to the piece you are working on

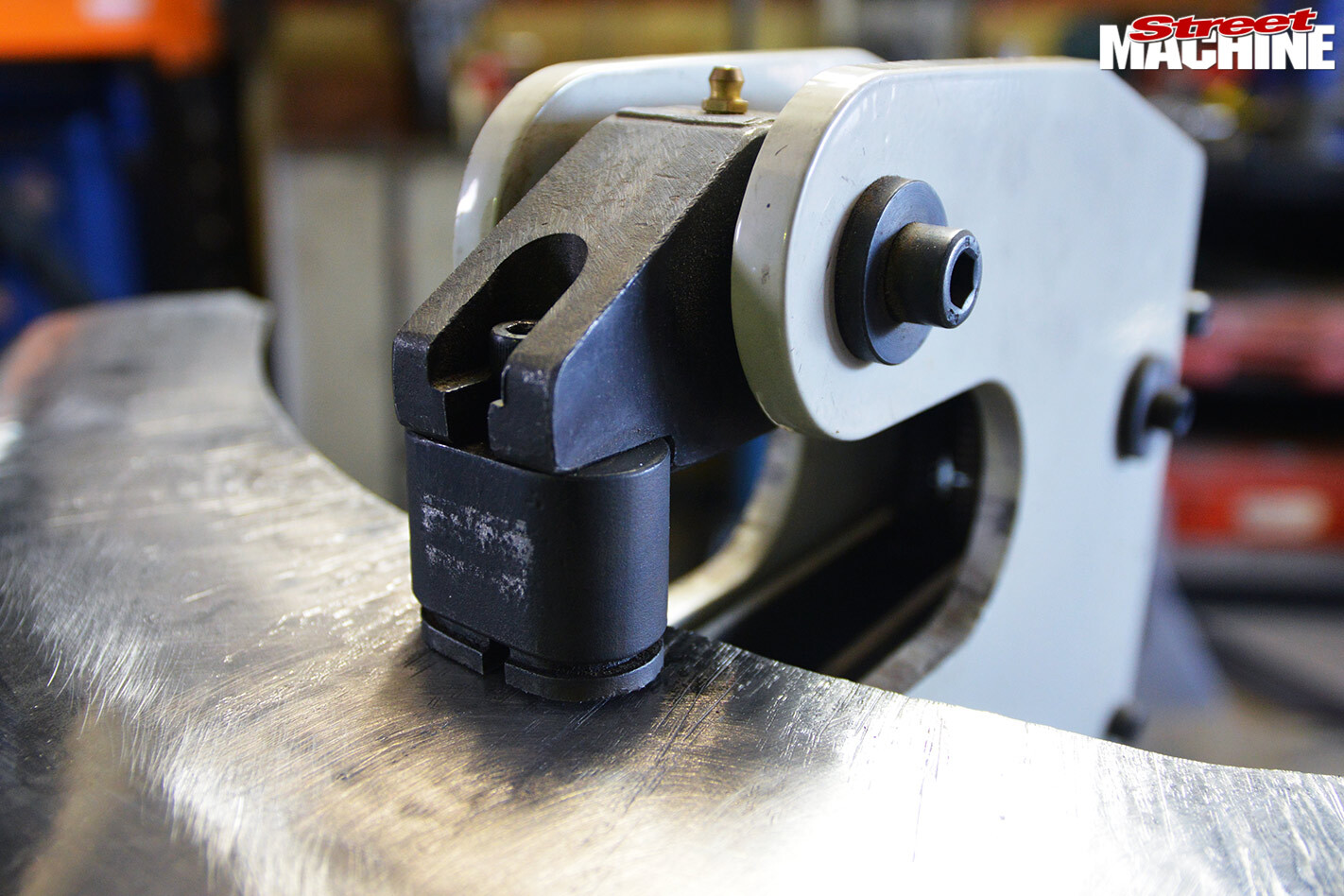

STEP 8. If more shrinking of the edge is required, tucking forks can be used to easily create more tucks. A few simple twists and we have a tuck. As shown earlier, this can be worked in from the sides, with the end then knocked down to lock it in

STEP 8. If more shrinking of the edge is required, tucking forks can be used to easily create more tucks. A few simple twists and we have a tuck. As shown earlier, this can be worked in from the sides, with the end then knocked down to lock it in

STEP 9. Back into the wheel we go for more planishing. Once again, choose an anvil that matches the contour of the work piece

STEP 9. Back into the wheel we go for more planishing. Once again, choose an anvil that matches the contour of the work piece

STEP 10. A stretcher-shrinker can be used to fine-tune things. The only downside of these machines is that they will leave marks on your work, but they are nonetheless very effective

STEP 10. A stretcher-shrinker can be used to fine-tune things. The only downside of these machines is that they will leave marks on your work, but they are nonetheless very effective

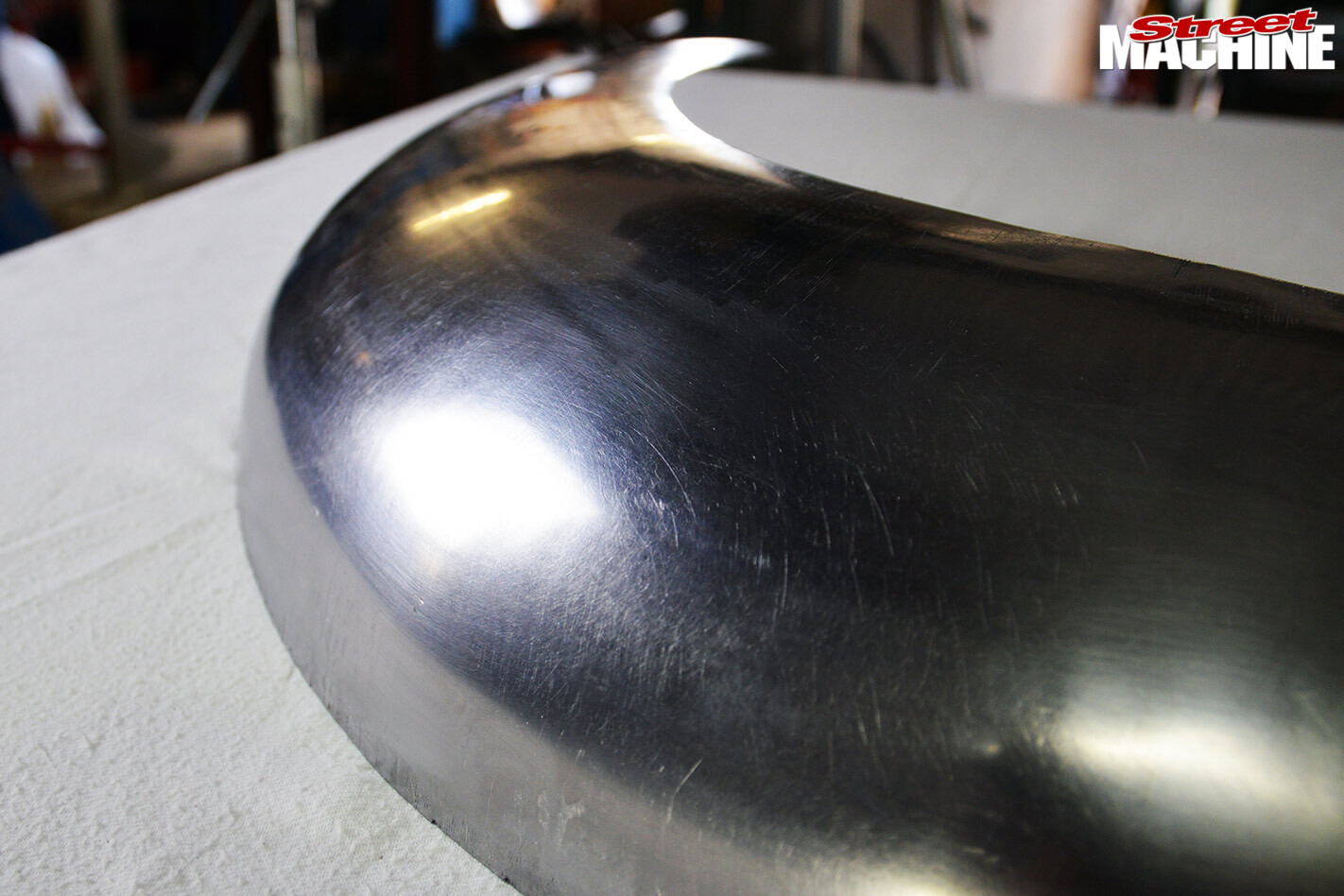

STEP 11. Here we see the results that can be achieved using these fairly simple techniques (above & below). Once the pieces are fixed solidly into position, metal filing and sanding can take place

STEP 11. Here we see the results that can be achieved using these fairly simple techniques (above & below). Once the pieces are fixed solidly into position, metal filing and sanding can take place

REMEMBER, you can only either stretch or shrink sheet metal. Once these basics are understood, the potential to create a one-off piece or repair something existing is unlimited. I hope this will inspire you to go out and have a crack. After all, I did!

REMEMBER, you can only either stretch or shrink sheet metal. Once these basics are understood, the potential to create a one-off piece or repair something existing is unlimited. I hope this will inspire you to go out and have a crack. After all, I did!

Comments