This article first appeared in the December 2018 issue of Street Machine

THERE’S something pretty fulfilling about being able to work on your own vehicle. None of us aspire to poor-quality work though, and unfortunately when it comes to the body side of things, it can be fairly easy to get flustered and just give up, or worse still, do the old bog ’n’ flog. This is the first in a series of tech features in which we’ll delve into some of the more technical aspects of metalwork, from rust repair to customisation. This is not necessarily a ‘how to’, but rather an insight into the world of automotive metalworking. As the saying goes, there’s a hundred ways to skin a cat, and it’s much the same with metal. While the basic principles of working with metal will always remain the same, the technology side of things is everchanging. So now the formalities are out of the way, it’s time we turn your attention to the job at hand – shaving a C-pillar vent on a 1976 XC Falcon 500.

STEP-BY-STEP

STEP 1. This car is getting a general tidy-up and STEP staying relatively stock, but a few extras will be smoothed out, such as the plastic vents on the rearmost section of the C-pillar.

STEP 1. This car is getting a general tidy-up and STEP staying relatively stock, but a few extras will be smoothed out, such as the plastic vents on the rearmost section of the C-pillar.

STEP 2. Once the plastic vent is removed we can really get a decent look at what we are up against.

STEP 2. Once the plastic vent is removed we can really get a decent look at what we are up against.

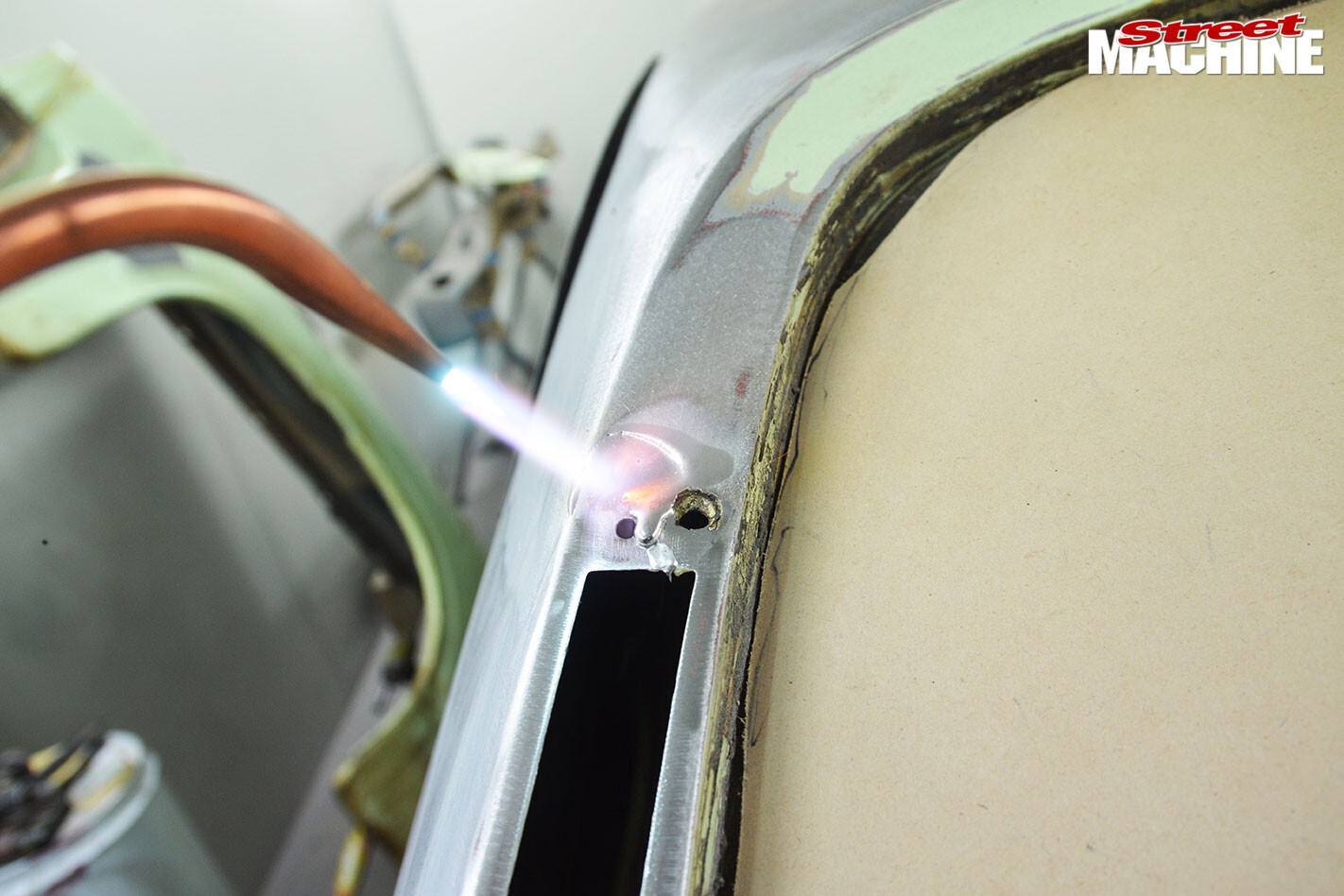

STEP 3. The uppermost section to be filled runs slightly into the factory lead join. This is easily melted away with either an oxy torch or a simple handheld butane torch. A wire brush will also be of assistance.

STEP 3. The uppermost section to be filled runs slightly into the factory lead join. This is easily melted away with either an oxy torch or a simple handheld butane torch. A wire brush will also be of assistance.

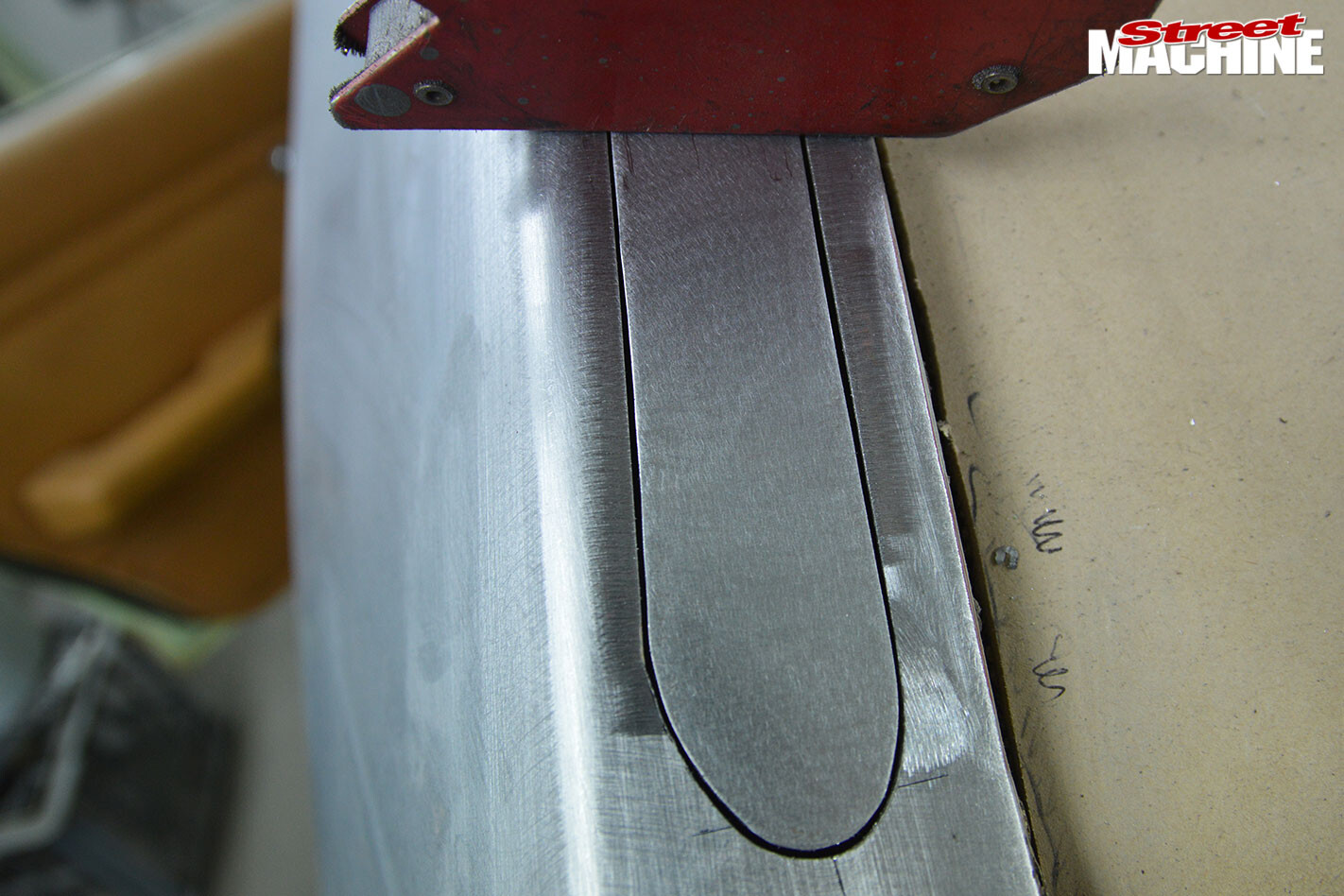

STEP 4. Both sections to be smoothed have hard corners. The idea here is to eliminate the ‘stop-start’ of a corner by cutting a curve into the metal with an air hacksaw (a die grinder will also suffice). This will help stop the metal from pulling and warping too much during the welding process. Instead of cutting away the centre section to make one big patch, it is left to help hold things in place.

STEP 4. Both sections to be smoothed have hard corners. The idea here is to eliminate the ‘stop-start’ of a corner by cutting a curve into the metal with an air hacksaw (a die grinder will also suffice). This will help stop the metal from pulling and warping too much during the welding process. Instead of cutting away the centre section to make one big patch, it is left to help hold things in place.

STEP 5. Cleanliness is everything. It may seem obvious, but getting rid of everything from paint to metal filings is a must for maximum penetration. Cleaning both sides of both the hole and the patch will greatly decrease the chance of porous welds if you are using a TIG.

STEP 5. Cleanliness is everything. It may seem obvious, but getting rid of everything from paint to metal filings is a must for maximum penetration. Cleaning both sides of both the hole and the patch will greatly decrease the chance of porous welds if you are using a TIG.

STEP 6. Matching the thickness of the car’s existing sheet metal, a piece of 1mm sheet is placed behind the opening and marked out with a scribe to get a nice, tight fit. It’s important to note that if you are using a MIG to do something similar to this, leaving a 1mm gap around your patch will allow for ‘weld creep’ and give you a much better result. However, if you are using a TIG or oxy to weld, getting that patch nice and snug in the hole will yield the best results.

STEP 6. Matching the thickness of the car’s existing sheet metal, a piece of 1mm sheet is placed behind the opening and marked out with a scribe to get a nice, tight fit. It’s important to note that if you are using a MIG to do something similar to this, leaving a 1mm gap around your patch will allow for ‘weld creep’ and give you a much better result. However, if you are using a TIG or oxy to weld, getting that patch nice and snug in the hole will yield the best results.

STEP 7. Time spent on getting the patch to fit properly will definitely save you headaches down the track. A nice sharp set of tinsnips, as well as hammering the edges of the patch back into shape before fitment, will see to that. Once you’re good to go, there are many ways to hold your piece into position. I simply tacked two pieces of scrap across the top so when placed onto the vehicle the patch sits flush and matches the car’s existing profile.

STEP 7. Time spent on getting the patch to fit properly will definitely save you headaches down the track. A nice sharp set of tinsnips, as well as hammering the edges of the patch back into shape before fitment, will see to that. Once you’re good to go, there are many ways to hold your piece into position. I simply tacked two pieces of scrap across the top so when placed onto the vehicle the patch sits flush and matches the car’s existing profile.

STEP 8. Once everything is tacked into place, it’s good to remove the two pieces of scrap and give the patch a bit of hammer-and-dolly action. This helps to get things sitting were they should be, as they tend to move around when heat is applied.

STEP 8. Once everything is tacked into place, it’s good to remove the two pieces of scrap and give the patch a bit of hammer-and-dolly action. This helps to get things sitting were they should be, as they tend to move around when heat is applied.

STEP 9. Small TIG welds approximately 1in in length can be used to stitch the metal together. This can be done by fuse welding if the patch is an excellent fit. In this case, 0.6mm MIG wire was used as fill to eliminate any undercut welds. While it may not look pretty now, you don’t want to hang around trying to make the 1mm mild steel look attractive at this stage. The key is to move from one side to the other to keep the heat down. If you are using a MIG, it’s the usual process of tacking, moving and cooling. Cooling is best done with an airgun and compressed air.

STEP 9. Small TIG welds approximately 1in in length can be used to stitch the metal together. This can be done by fuse welding if the patch is an excellent fit. In this case, 0.6mm MIG wire was used as fill to eliminate any undercut welds. While it may not look pretty now, you don’t want to hang around trying to make the 1mm mild steel look attractive at this stage. The key is to move from one side to the other to keep the heat down. If you are using a MIG, it’s the usual process of tacking, moving and cooling. Cooling is best done with an airgun and compressed air.

STEP 10. Once fully welded, the TIG welds are easily knocked down with an air sander (36-grit, then 80-grit), being careful to keep the heat down. Undoubtedly the best part of having TIGwelded a piece like this is that it will remain fairly malleable and can still be worked with a hammer and dolly to ‘relieve’ the metal, bringing everything back into place where it needs to be. At this stage, the little section between the two openings is cut away and the same process is repeated on the hole above.

STEP 10. Once fully welded, the TIG welds are easily knocked down with an air sander (36-grit, then 80-grit), being careful to keep the heat down. Undoubtedly the best part of having TIGwelded a piece like this is that it will remain fairly malleable and can still be worked with a hammer and dolly to ‘relieve’ the metal, bringing everything back into place where it needs to be. At this stage, the little section between the two openings is cut away and the same process is repeated on the hole above.

STEP 11. Now if you want to get real fancy and desire a finish that is more pleasing to the eye, the entire area can be worked with hammer/dolly and metal file, eventually working up to finer-grit sandpaper. This can take hours, but the results speak for themselves. This process can easily be replicated for any hole that needs to be filled.

STEP 11. Now if you want to get real fancy and desire a finish that is more pleasing to the eye, the entire area can be worked with hammer/dolly and metal file, eventually working up to finer-grit sandpaper. This can take hours, but the results speak for themselves. This process can easily be replicated for any hole that needs to be filled.

Hopefully this small insight will help you whenyou face a similar task, or even provide some much-needed inspiration to get motivated and get that project back onto the blacktop!

Comments