THE art of hand-forming sheet metal into complex shapes almost seems like black magic in this age of high-volume production and exotic materials. But thankfully there are those among us who still know one end of an English wheel from the other and aren’t scared of a planishing hammer.

Which brings us to Jamie Downie and Nate Browne from Kustom Garage in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. One of their biggest projects in the past year has been creating the rear quarters and door skins on Peter Sharp’s SHQRP Monaro; a project that was sub-contracted out to them by the guys at Taree’s Down Town Kustoms (DTK).

DTK has been transforming this HQ Monaro into a wide-body supercar for well over 12 months now, and stripped the shell right down to its skeleton. We’ve covered some of the previous work in SM, June and July 2014, but since then the guys have moved on to the massive rear quarters. Creating these from scratch is difficult enough, but ensuring they are exact opposites is a huge job, so DTK farmed it out to Jamie at Kustom Garage.

DTK has been transforming this HQ Monaro into a wide-body supercar for well over 12 months now, and stripped the shell right down to its skeleton. We’ve covered some of the previous work in SM, June and July 2014, but since then the guys have moved on to the massive rear quarters. Creating these from scratch is difficult enough, but ensuring they are exact opposites is a huge job, so DTK farmed it out to Jamie at Kustom Garage.

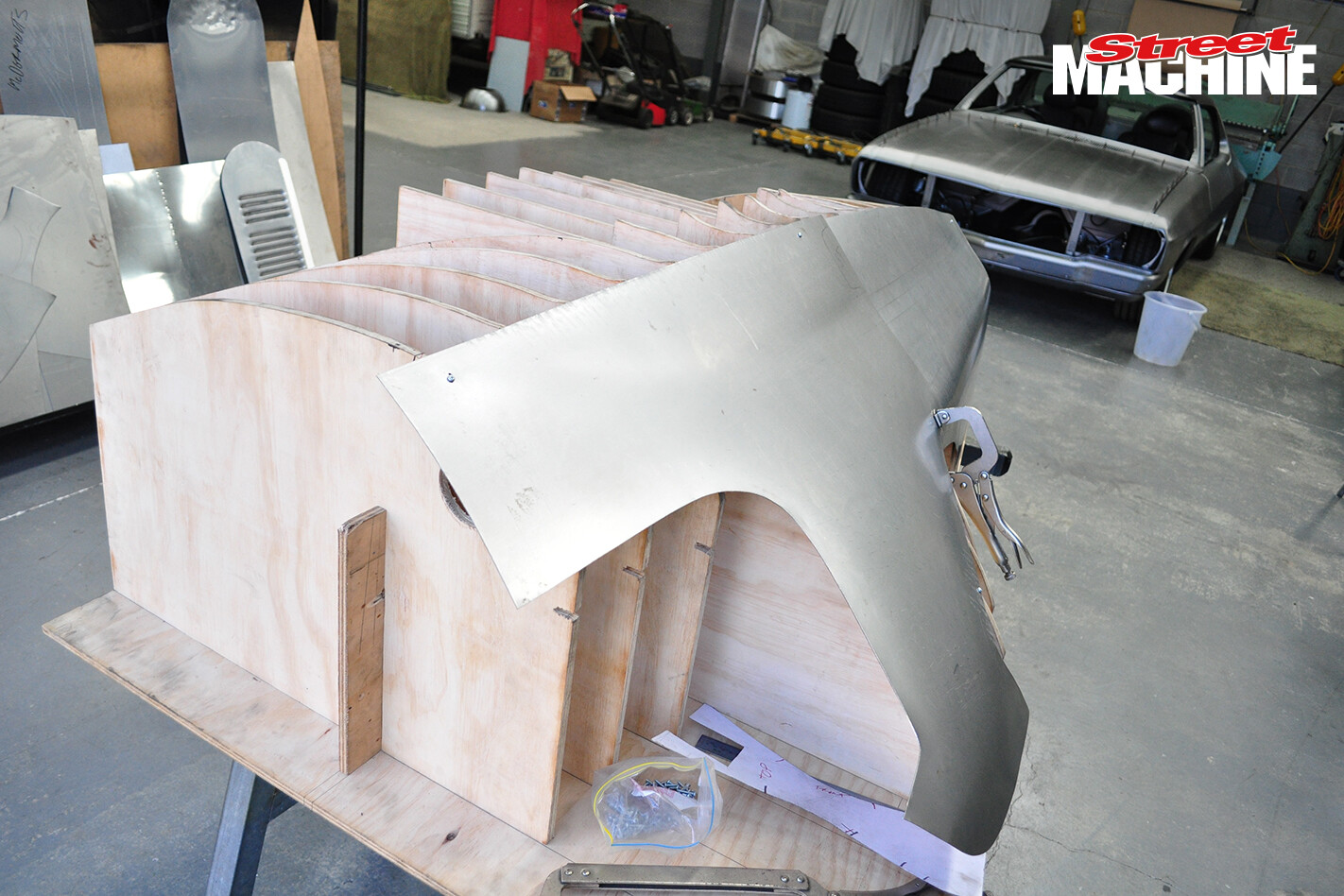

“Graeme came down with one of the original quarter panels off the car and together we spent a week working to create the shape that they wanted.” Once they had the shape sorted, Jamie and Nate created a wooden buck out of thick plywood and used that to make reversible paper patterns and templates so they could transfer the shapes to flat steel sheet and get the job underway.

“Graeme came down with one of the original quarter panels off the car and together we spent a week working to create the shape that they wanted.” Once they had the shape sorted, Jamie and Nate created a wooden buck out of thick plywood and used that to make reversible paper patterns and templates so they could transfer the shapes to flat steel sheet and get the job underway.

When we joined the boys at Kustom Garage they had already finished the passenger-side rear quarter and door skin on SHQRP. The original job was to do just the quarter, but the door skins then needed to be redone to smooth the transition from front to rear

When we joined the boys at Kustom Garage they had already finished the passenger-side rear quarter and door skin on SHQRP. The original job was to do just the quarter, but the door skins then needed to be redone to smooth the transition from front to rear

Jamie and Graeme worked together to create the sample quarter within a week. They use that to create the wooden buck, and form the two quarters that will eventually go on the car

Jamie and Graeme worked together to create the sample quarter within a week. They use that to create the wooden buck, and form the two quarters that will eventually go on the car

The wooden buck outlines the shape of the rear quarter and is reversible by swapping the pieces from one side of the backing board to the other

The wooden buck outlines the shape of the rear quarter and is reversible by swapping the pieces from one side of the backing board to the other

Paper patterns were created off the original sample panel. They show the size and shape of each piece and are held in place by small magnets. When laid on a flat piece of sheet steel the pattern is used to outline the shape of each section

Paper patterns were created off the original sample panel. They show the size and shape of each piece and are held in place by small magnets. When laid on a flat piece of sheet steel the pattern is used to outline the shape of each section

Jamie uses a pen over the top of the paper templates to score out the shapes of the four separate pieces that will make up the rear quarter, while Nate uses masking tape to show the lines clearly

Jamie uses a pen over the top of the paper templates to score out the shapes of the four separate pieces that will make up the rear quarter, while Nate uses masking tape to show the lines clearly

Here are the four pieces marked out on a fresh piece of 1mm CA3-grade steel sheet. Creating the rear quarter out of one single piece is possible, Jamie says, but would be much harder to manage due to its unwieldy size

Here are the four pieces marked out on a fresh piece of 1mm CA3-grade steel sheet. Creating the rear quarter out of one single piece is possible, Jamie says, but would be much harder to manage due to its unwieldy size

The boys use an air nibbler to cut out the rough shapes quickly, staying well outside the masking tape boundary. The size of the main sheet makes it too hard to cut the pieces out with any kind of precision at this point

The boys use an air nibbler to cut out the rough shapes quickly, staying well outside the masking tape boundary. The size of the main sheet makes it too hard to cut the pieces out with any kind of precision at this point

Hand shears are used to cut away the excess from each piece. Doing this by hand is time consuming and tiring, but the precision is worth it. Then the tape is peeled away and the edges are filed

Hand shears are used to cut away the excess from each piece. Doing this by hand is time consuming and tiring, but the precision is worth it. Then the tape is peeled away and the edges are filed

Here are the four pieces in a flat arrangement as they will sit relative to the HQ. There’s a stack of work to be done to create the necessary curves and body lines – time to bring in the big guns

Here are the four pieces in a flat arrangement as they will sit relative to the HQ. There’s a stack of work to be done to create the necessary curves and body lines – time to bring in the big guns

The biggest metal-shaping tool in Jamie’s workshop is Yoder, a 1942 power hammer weighing in at three tonnes. It does the same job as an English wheel – shaping panels – but uses a cyclical up-and-down motion controlled by a speed-sensitive foot pedal. Definitely requires ear-protection!

The biggest metal-shaping tool in Jamie’s workshop is Yoder, a 1942 power hammer weighing in at three tonnes. It does the same job as an English wheel – shaping panels – but uses a cyclical up-and-down motion controlled by a speed-sensitive foot pedal. Definitely requires ear-protection!

Remember the paper patterns? Well they have measurements all along them that correspond to points on each panel, and these cardboard templates are used to check the shape of the curves

Remember the paper patterns? Well they have measurements all along them that correspond to points on each panel, and these cardboard templates are used to check the shape of the curves

The buck also comes in handy for holding pieces in place. Here, Jamie has the top of the rear quarter fixed in the correct position while he works the back corner into shape

The buck also comes in handy for holding pieces in place. Here, Jamie has the top of the rear quarter fixed in the correct position while he works the back corner into shape

From there it’s back to Yoder to shrink the metal of that same back corner. “Other than speed, this is the main advantage of a power hammer over an English wheel,” Jamie says. “You can stretch metal with an English wheel, but you can’t shrink it”

From there it’s back to Yoder to shrink the metal of that same back corner. “Other than speed, this is the main advantage of a power hammer over an English wheel,” Jamie says. “You can stretch metal with an English wheel, but you can’t shrink it”

The Pullmax can do all kinds of things depending on the dies used. In this case Nate is making a fold line on the edge of the panel. Like the power hammer, the bottom die is stationary while the top die rapidly cycles up and down

The Pullmax can do all kinds of things depending on the dies used. In this case Nate is making a fold line on the edge of the panel. Like the power hammer, the bottom die is stationary while the top die rapidly cycles up and down

Not everything can be done with power tools; there’s still plenty to do with the good old hammer and dolly. The bag on top of the panel, filled with lead shot, helps hold the piece in place

Not everything can be done with power tools; there’s still plenty to do with the good old hammer and dolly. The bag on top of the panel, filled with lead shot, helps hold the piece in place

The shrinker/stretcher does exactly what you think. Two pairs of jaws clamp on the edge and pull away from each other to stretch, or push towards each other to shrink, which helps make curves in panel edges

The shrinker/stretcher does exactly what you think. Two pairs of jaws clamp on the edge and pull away from each other to stretch, or push towards each other to shrink, which helps make curves in panel edges

With the two top pieces roughly in the correct shape, they’re screwed to the buck in preparation for welding together. The two bottom pieces will also be welded together to create an upper and lower section

With the two top pieces roughly in the correct shape, they’re screwed to the buck in preparation for welding together. The two bottom pieces will also be welded together to create an upper and lower section

With two halves bent, beaten and pressed into shape, they’re screwed to the buck and the overlapping material is removed. Any remaining excess is trimmed away with hand shears so the two halves butt up against each other

With two halves bent, beaten and pressed into shape, they’re screwed to the buck and the overlapping material is removed. Any remaining excess is trimmed away with hand shears so the two halves butt up against each other

Now the pieces are carefully TIGed together, with the buck holding them in place. Jamie likes to tack the panels together first with no filler rod, then he goes over all the joins with the rod

Now the pieces are carefully TIGed together, with the buck holding them in place. Jamie likes to tack the panels together first with no filler rod, then he goes over all the joins with the rod

And here we are, the first time the rear quarter is together as one single piece, but there’s plenty left to do. The boys don’t grind the weld off; they work it with a hammer and dolly and then smooth it flat with an adjustable body file

And here we are, the first time the rear quarter is together as one single piece, but there’s plenty left to do. The boys don’t grind the weld off; they work it with a hammer and dolly and then smooth it flat with an adjustable body file

Time to test-fit the panel to the car. It’s really starting to take shape now and you can see where the custom bumper has been recessed into the rear, requiring some modification to the panel

Time to test-fit the panel to the car. It’s really starting to take shape now and you can see where the custom bumper has been recessed into the rear, requiring some modification to the panel

The bumper recess is clamped into place prior to welding. Because of the shape, the recess has been created separately and needs to be welded in. As before, Jamie will tack the piece into place using the TIG without filler

The bumper recess is clamped into place prior to welding. Because of the shape, the recess has been created separately and needs to be welded in. As before, Jamie will tack the piece into place using the TIG without filler

This is precision welding. There’s no point dumping excessive heat into the panel, especially with a non-structural piece like this. That just creates more work; they don’t grind the welds smooth for the same reason

This is precision welding. There’s no point dumping excessive heat into the panel, especially with a non-structural piece like this. That just creates more work; they don’t grind the welds smooth for the same reason

The last piece of the puzzle is the rear window sill, which has to be formed separately before it’s welded into position. Imagine trying to create all those curves while wrangling the whole panel around

The last piece of the puzzle is the rear window sill, which has to be formed separately before it’s welded into position. Imagine trying to create all those curves while wrangling the whole panel around

Hammers, dollies and body files are the tools of the trade when it comes to finishing off the sheet metal. But you’ll need a whole lot of experience, skill and patience to create metal magic like you’ve seen here

Hammers, dollies and body files are the tools of the trade when it comes to finishing off the sheet metal. But you’ll need a whole lot of experience, skill and patience to create metal magic like you’ve seen here

And here’s the finished product – or finished from Jamie’s end, anyway. The whole job – from creating the buck to the completed rear-quarters and door skins – took 350 hours, or to put it another way, nine weeks of eight-hour days full-time

And here’s the finished product – or finished from Jamie’s end, anyway. The whole job – from creating the buck to the completed rear-quarters and door skins – took 350 hours, or to put it another way, nine weeks of eight-hour days full-time

Comments