It took about 10 minutes for the world to discover how choked up General Motors’ Gen III and Gen IV LS engines were from the factory. That’s why we’ve seen huge power made from them using bus turbos, aftermarket blocks or huge blowers. But the factory alloy LS shouldn’t be discounted, as it can be built into an awesome daily driver and weekender with a minimum of fuss and expense.

First seen in Australia in 1999’s Series II VT Commodore, the 5.7-litre LS1 delivered us a sniff under 300hp, before subsequent Commodore generations saw this figure gradually increase to a high of 408hp with the 6.2-litre Gen IV LS3 in the 2017 VF II Commodore.

The LS platform also provided wild possibilities for the factory speed offerings from HSV. Off the bat, HSV launched the legendary VT II GTS packing a 400hp Callaway-tuned LS1, but also stuck a range of 400-505hp atmo LS variants into their cars through the next two decades. Things got spicy in 2013 when the company introduced boost to the range with the 580hp supercharged LSA, which went into the VF I GTS and then a range of VF II models.

The LS variants can seem confusing, but the recipe for most beginner modifiers is simple no matter which alphanumeric code is on your engine. You’ll be able to squeeze up to 400rwhp out of a 5.7 with stock heads and careful cam selection, though 400-450rwhp is far easier to achieve with the Gen IV platform thanks to its increased capacity, better-breathing heads and superior ECU.

Traditionally, many looking to spice up an LS engine started with an over-the-radiator intake, stiffer valve springs, freer-flowing exhaust, and a flash tune of the stock ECU. The stock 4L60E four-speed automatic transmission used in pre-VE Commodores won’t like those mods in partnership with spirited driving, so those wanting to push their late-model Commodore often jump straight to a TH400 three-speed or 4L80E electronic auto.

The stock LS bottom ends feature strong steel crankshafts and six-bolt main caps, which help these engines hang together with double the factory output. But there are a few key weaknesses in LS mills, depending on the model.

All LS engines are prone to oil control issues when you’re going hard in the twisties, and the factory valve springs are flimsy in the stock set-up. If you’re building a rig you’ll take on the circuit, it would pay to upgrade the sump with something that can prevent oil sloshing around, or take preventative measures like adding a little bit of oil before the track day.

Weaknesses among Gen IV donks include the cam bearings in the L98, and the Displacement On Demand or Active Fuel Management lifters and buckets in 6.0-litre engines. While this tech wasn’t active on manual VE I and VF II models, the troublesome lifters and buckets were still fitted, and they will eventually fail and wipe out the cam lobes. Today, many street machiners will spend the money to pull these aging engines and do some basic servicing. These include replacing the oil pump and timing chain, throwing a fresh sump gasket and rear covers on, and upgrading the factory cam.

GM equipped the LS with a bumpstick so smooth it could double as a broomstick, but that is easily swapped out for something more aggressive. However, don’t just go throwing the biggest, angriest cam you can find on the internet into a stock motor, as you’ll run into piston-to-valve clearance issues. Keep your cam on the tamer side of 242/248/110, which is regarded as the largest off-the-shelf item you can fit without having to fly-cut pistons for valve clearance. Any cam upgrade will need pushrod length checked to ensure the valves open and close properly, and many will need a MAFless dyno tune, as the amount of air they’ll flow is greater than what the factory air-flow sensor is scaled for.

The best option is to switch to genuine LS7 lifters and buckets, which have been proven in many 1000hp combos. Tie-bar lifters are also available, but these are considered unnecessary by many engine builders unless you’re putting together a high-rpm or big-power LS.

Most people reading Street Machine will go for 17/8-inch headers, while a twin three-inch exhaust system will liberate slightly more power on a cammed, tuned 6.0-litre or 6.2 than a twin 2.75-inch system, but it will also be significantly louder.

VE-on ECUs are easily flash-tuned thanks to their vastly improved computing power and tuning resolution compared to the older non-CAN bus VT-VZ PCMs. Factory flex-fuel options for VE II to VF I cars add allure, but E85 won’t make a huge difference to power in a cammed LS with a stock rotating assembly.

All LS-equipped Holdens offer great bang-for-buck today and can be made into properly quick, comfortable rides for the whole family with fairly basic work. So don’t discount late-model Commodores as project sleds!

ENGINE TROUBLE

MPW Performance‘s Adam Rogash is no stranger to Street Machine readers, as his twin-turbo LS-powered Commodores have both run seven-second ETs. In addition, MPW is well known for turning out countless spicy LS combos for customers, and this work hasn’t slowed down for the Keysborough, Victoria outfit. “We do heaps of cam swaps and a lot of daily driver packages,” Adam says.

With LS-powered Holdens ranging from 6 to 24 years of age, finding beautifully cared-for vehicles to use as a solid base for a build can be tricky, so it’s risky to think you will be able to take an unknown car and simply stick a grumpy bumpstick in.

“As soon as you get a lot of kilometres on [LS engines], and if they haven’t been serviced, they’ll eat the cam bearings,” says Adam. “LS engines wear through the Babbitt coating on the cam bearings, which means you’re up for a full engine build, and there is no way to see what the cam bearings are like until you pull the cam out.

“Trunnions, timing chains, and oil pressure relief valves fail all the time, and I never go single valve springs,” he continues. “I never recommend a factory timing chain; I prefer the pressed-link Cloyes chain. We’ve had dramas with certain tie-bar lifters, so we go LS7 lifters in all our basic combos, and for over-1000hp combos, we put a Johnson high-rpm tie-bar in.”

GENERATION GAP

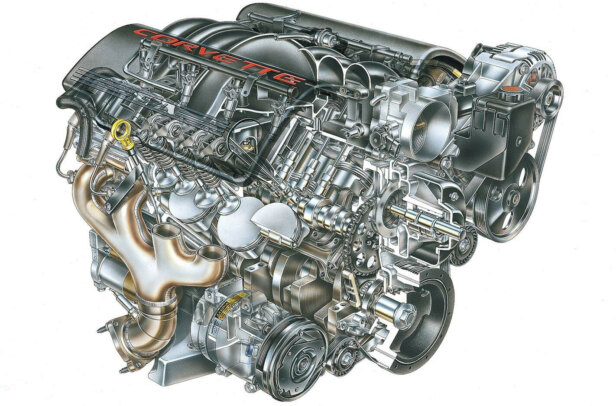

Gen III and Gen IV engines may look very similar, but there were huge upgrades done to almost every part of the long motor and electronics package for the Gen IV, which can make the later-model engines more attractive for hotting up.

Earlier engines are easily identified by cable throttlebodies, cathedral-port cylinder heads, two knock sensors in the valley, and the cam position and oil pressure sensors in the back of the valley. Gen IV engines will have a cam sensor in the timing cover, knock sensors on the side of the block, rectangle-port cylinder heads, and drive-by-wire throttle.

Inside, the Gen III runs a 24-tooth reluctor wheel on the crank for positioning, while the Gen IV scores a 58-tooth wheel for improved resolution. The ECU on Gen IV engines is a significant improvement over earlier PCMs, as it’s easier to tune and offers more features.

While it’s common to think that Gen IV V8s were first seen in VE Commodores, there were also limited-edition VZ models, including the SS Thunder ute, that scored 6.0L power.

- 1. Swapping to shorter diff gears from HSV models and changing to a tighter converter or single-mass flywheel will bring excellent gains on aspirated SBE combos, and will often make the car snappier off the throttle.

2. A single-row timing chain is all a stock-bottom-end LS will need, as fitting a dual-row chain requires machining the crank snout to let the chain run true with the top sprocket, and a casting lug in the timing cover needs to be ground back, too.

3. One of the appeals of the LS is its overall reliability when properly maintained. Oil often leaks from the front and rear timing covers on old, high-kilometre or hard-revved engines, but they generally copped more abuse than the venerable iron lion the LS replaced.

4. Their stock valve springs are weaker than a sick kitten, so LS mills with stock rotating assemblies will generally need an upgrade to a quality spring. The needle bearings in the stock rocker arms are renowned for failing, too, so throwing in a trunnion upgrade kit is almost a requirement these days.

5. I’ve owned plenty of LS-powered cars over the years, and my favourite was this 2013 VF SS-V ute. After a Displacement On Demand failure, it copped a VCM OTR intake and 883-grind cam, PAC valve springs, VCM pushrods, LS7 lifters and buckets, a twin 2.5in exhaust and 17/8in headers, and a single-mass flywheel to make 405rwhp.

6. Finding a cam that fulfils your horsepower desires without pushing through a stock converter or being a pain at low revs can take a little research. I’ve seen excellent results in more than a dozen friends’ daily drivers and weekenders with a cam of around 228/238/113.

7. For aspirated set-ups, the factory fuel system will do all you’ll need of it, but there may be maintenance parts required on high-mileage cars, like a fuel pump and filter, or an injector service. Fortunately, one of the benefits of choosing an LS platform is that parts are available everywhere.

8. There are plenty of bolt-on cylinder head upgrades available from Higgins, Texas Speed, Trick Flow and more. Unless you’re planning on building a big combo later, the stock heads will normally be fine for up to around 400rwhp.

LS ESSENTIALS

TO THE MAX

The newest addition to Proflow’s range of LS products is this SuperMax Plus intake manifold. A nicely CNC-machined piece, it’s designed for big-horsepower LS engine applications. “This is the top-level intake in our range, suited to big boost and horsepower builds,” says Jake Cugnetto of VPW Australia, which makes the Proflow products. “We’ve had a lot of demand for this one, and as a cool benefit, it looks as good as it performs.”

The SuperMax Plus is made to suit both cathedral- and rectangular-port heads, with a 102mm throttlebody opening. Other neat features include radiused internal runners for smooth airflow, a low-profile lid, and billet fuel rails and fittings. You also get a provision for a GM MAP sensor, four vacuum ports neatly mounted at the back, and all the mounting hardware needed to install.

MENTAL BLOCK

The locally delivered alloy-block LS engines do have their limits, especially when shoved with a fist-load of boost. If you’re getting super serious with your boost levels, then a Dart LS block is probably your best bet. VPW now offers Dart LS Next short-block kits; they’re 427ci packages based around LS3/LS7 architecture. “They’re the big boy; we see those going out to customers chasing serious performance, usually with our top-range parts to match,” says Jake from VPW Australia.

The kit includes the block, K1 forged crank, H-beam rods and Wiseco flat-top pistons, all internally balanced. VPW can then help you spec out the rest of the gear like heads, intake, sump and so on from their extensive range.

PRIME THE PUMP

Keeping your LS cool is important, but even from factory, LS water pumps are known to spring a leak. Mechanical, belt-driven water pumps also suck away horsepower and can run into flow rate problems at high revs. An electric water pump can solve all these problems, which is why Proflow offers this billet-aluminium water pump. “They flow a lot more than a mechanical one, and help prevent cavitation in the cooling system as well,” says Jake from VPW.

Designed to fit all LS engines, the pump can flow up to 132 litres per minute, and the billet housing can easily handle the hot liquids. Wiring is a simple process, and Proflow even includes all the gaskets you need for a simple installation.

PANNING OUT NICELY

If you’re swapping your LS into a non-LS chassis, you’ll probably need to address sump clearance. VPW Australia offers both front and rear RTS sumps to suit LS, so you just have to choose the right one for your application. Made from fabricated aluminium, the sumps have cool features like an integrated oil drain, increased ground clearance and anti-slosh baffles, and they also include the oil pick-up to match.

“These are very popular with buyers doing engine swaps, but they also suit LS Commodores for those looking to upgrade their oiling,” says VPW’s Jake Cugnetto. “Both sumps come with remote oil filter kits as well to make swaps easy, so as you can imagine, they’re a popular item for us.”

FLEX TIME

Soon to be added to VPW’s range of LS kit is this RTS billet flexplate. Upgrading your flexplate is important when you’re shoving more power through your driveline, as it’s often a weak point. “These are new for us, as we found a lot of buyers chasing a billet one with SFI certification,” says Jake.

“We only did an upgraded steel one until now, but having a billet one is good insurance for your driveline, and [being SFI-certified] means it’s easy to get the car teched for racing.”

TUNNEL OF LOVE

If you want to be loud and proud with your aspo LS, then a tunnel-ram intake is the hot ticket. Proflow has now taken its tunnel ram manifold and turned it into a complete kit, making it easier to get everything you need in one go. “We were selling it all individually, but we found them to be quite popular – especially with the burnout guys – so we made it into a package to simplify the process,” says Jake of VPW Australia.

“It also comes out a bit cheaper if you buy the kit, so it’s a good addition to our range.” The kit includes the manifold, a pair of EFI quad throttlebodies, air filters and spacers, gaskets, and the all-important throttle linkages.

Comments