THE few short years between 1968 and 1972 really were the halcyon days of the muscle cars we all know and love. It was a time when auto manufacturers truly lived by the ‘Win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ mantra and used NHRA drag racing, NASCAR and the Trans Am series to showcase the hottest models coming off their production lines.

This article was first published in the July 2013 issue of Street Machine

While Ford invented the pony car in 1964 with the introduction of the Mustang, by 1968 the once compact and nimble car had put on a few pounds and wasn’t quite living up to its high-performance image. The kick in the bum that Ford needed came when it lost the Trans Am championship to Chevrolet and its Camaro in 1968.

And Chevrolet was not only the catalyst, it also supplied quite a bit of the brain power for the rejuvenation of the Mustang line. After a stellar career where he turned around Pontiac and then went on to become an executive vice president of GM, Semon ‘Bunkie’ Knudsen jumped ship after losing out in the battle for the top job to Ed Cole.

Henry Ford II made him an offer that was too good to refuse and along with a bunch of clever engineers, Knudsen convinced stylist Larry Shinoda to join him at Ford. Like Knudsen, Shinoda was a certified gearhead and together they would create what would become arguably the greatest and most desirable Fords of all time — the Boss Mustangs.

BOSS 429

THE first of the Boss Mustangs to roll off the line on 15 January 1969 was the 429. Its sole purpose was to homologate the hemi-headed 429ci engine for NASCAR racing so that Ford could compete with Chrysler’s 426 Hemi. By the time Knudsen arrived at Ford in late ’68, the development of the engine had been completed, so he had to decide where to stuff at least 500 of them for homologation purposes.

The problem is, the Boss is a big engine – 30 inches (762mm) wide – and it would barely fit in full-size Fords and Mercurys. Stuffing it into a Mustang would take some serious surgery, the kind of work that assembly lines don’t like. To create the Boss 429s, Ford turned to Kar Kraft Engineering, a Ford racing sub-contractor that had been responsible for much of the work that went into the Ford GT program that beat the Ferraris at Le Mans.

To create the Boss 429, Kar Kraft took delivery of a Mach 1 428 Cobra Jet, removed the engine and suspension then took to the shock towers with a gas axe. With the Mustang engine bay no more than 28 inches (711mm) wide, they had to find a few extra inches somewhere. Specially modified shock towers were installed and extra bracing added to cope with the extra load of the Boss 429.

Widening the engine bay also pushed out the suspension an inch each side, which required the upper control arms to be lowered an inch. The lower control arms had to be reworked to ensure the steering geometry was still correct and all Boss Mustangs were fitted with large-diameter spindles to handle extra cornering loads – or in the case of the Boss 429, to take the extra weight of the engine!

Although the Boss 429 was fitted with sizeable sway bars, 0.94in in the front and 0.62in on the rear, in an attempt to help get the front-heavy Mustang around corners, it was never going to be a canyon carver. To make matters worse, the engine had to be mounted one inch higher and an inch further forward than the 428 to fit in the engine bay – not exactly the ideal recipe for going around corners. That would be the Boss 302’s domain; the super speedways and dragstrips were where the Boss 429 would strut its stuff.

The word behemoth comes to mind when looking at the engine bay of a Boss 429. An extra couple of inches of width were found by chopping out the shock towers; the engine was moved up and forward an inch to fit

To handle the stresses of racing, the Boss 429 was built to be bullet proof. The forged and cross-drilled steel crank was held in with four-bolt mains, while the massive rods were clamped on with ½in bolts; with each conrod weighing more than 1kg, it was vital. The forged pistons squeezed out 10.5:1 compression and the heads were sealed with O-rings. Pretty serious stuff. This was the specification for the S-code engine, which was fitted to the first 279 cars built — James’s car is KK1245 and was number 33 off the line, hence it has the S-code engine.

The S-code also came with a fairly mild hydraulic cam with just over 500 thou lift, even though the stock pistons were fly-cut to handle at least 600 thou. With only 735cfm of Holley to breathe through – the smallest carb offered on any Boss Mustang – the street version of the Boss 429 performed nowhere near its full potential. The remainder of the 1356 cars built mostly had T-code engines, which featured lighter conrods and a more aggressive solid cam.

Magazines of the day clocked low 14-second passes at just over 100mph. With a few tweaks low 12s were quite achievable, but remember, these cars had to be warrantied across all 50 states, from Alaska to Texas. Although successful in homologating the engine for NASCAR racing, the Mustang was never used for NASCAR. That honour – and the 1969 championship – went to a Torino Talladega. It also sent Chrysler back to the drawing board and they developed the Dodge Charger Daytona and Plymouth Superbird, proof that racing really does improve the breed.

BOSS 302

WHILE the Boss 429 was built to go in a straight line and through the odd left-hand bend, the Boss 302 was designed to turn both left and right, to stop and go and ultimately snatch back the Trans Am championship from Chevrolet. The order from Knudsen therefore was pretty straightforward – the cars needed to be invincible on the track, while the street-going versions had to look every bit as unbeatable.

Former GM stylist Larry Shinoda was fascinated by aerodynamics. He had the car’s lines cleaned up, removing the non-functional scoops on the rear quarters and the roof pillar badge. He also insisted on the rear deck spoiler as an option, although none of the race teams ran them

Getting the cars to handle was of prime concern and that task was handed to Matt Donner, the Chief Ride and Handling Engineer. Even though it was touted as a sports car, like most American cars at the time, understeer was the order of the day. For your average low-performance driver on the street that’s not a problem, but if you want to get around corners in a hurry then you need to get that front end going where it’s pointed.

What Donner came up with was the ‘competition suspension package’, which comprised much stiffer compression and rebound rates, a beefier front sway bar and a heavy-duty front spindle that could handle the extra loads. The handling was also helped by the first use of 60-series tyres on a mass production vehicle. The F60-15 Goodyear Polyglas tyres were so fat that the front guards had to be cut and rolled to clear them.

With dismal performance and reliability problems from the exotic tunnel-port 302 used during the 1968 Trans Am series, Ford had to come up with an engine that would hang together under the extremes of circuit racing. They also had to build at least 1000 of them to keep the SCCA happy.

Using the tunnel-port block, which featured four-bolt mains and screw-in core plugs, as the basis for the new race engine, the boffins at Ford soon discovered that the heads slated for the new Cleveland engine would bolt straight on with little modification. With massive 2.23in intake valves and 1.71in exhaust valves there would be no problem with breathing. Boss heads also came with guide plates, machined spring cups and heavy-duty dual springs over the standard 4V heads.

The internals were suitably beefy as well. With forged and cross-drilled cranks for 1969 (dropped in 1970), forged rods and pistons, a cranky solid lifter cam and a 780cfm Holley on a high-rise dual-plane intake, the little 302-cuber was built to scream and to last. The engines also ran windage trays, baffled sumps and a factory-installed rev limiter – the first thing people disconnected – to give it the best chance of survival.

Externally the cars were subtly different from the regular Mustangs, even the Boss 429. Shinoda insisted that anything that wasn’t functional on the Mustang wasn’t going to be on the Boss 302, so those fake air ducts on the rear quarters and the Mustang badge on the roof pillar had to go. It’s a small difference that took a lot of effort to change but Shinoda insisted and he eventually got his way.

The first Boss 302s didn’t hit the streets until 17 April 1969 and Ford built 1628 of the high-stepping beauties. Buyers had a choice of only four colours: Wimbledon White, Acapulco Blue, Bright Yellow or Calypso Coral. You could pick any colour interior you wanted from the 1969 catalogue but, not surprisingly, most people opted for black vinyl.

For 1970, the rules were changed so that each manufacturer had to create 2500 units – bad enough – or 1/250th of 1969 production. In Ford’s case, that meant they had to build 6500 street versions of the Boss 302 before they could go racing. Once the dust settled and the spanners were put away, 7013 rolled off the assembly line, considerably more than any other Boss Mustang.

The front-end styling changed to a two-headlight arrangement with fake air scoops outboard of the lights. The racers tried to get away with using them as cooling ducts for the brakes, but the officials caught on pretty quickly. You have to wonder why Ford didn’t just punch the panel out anyway. The big news for 1970 was the availability of a Ram Air option – your basic shaker scoop – which proved very popular. Interestingly, the race cars didn’t run the shaker set up, and although it undoubtedly increased horsepower, advertised ratings were the same as 1969 – 290hp and 290lb-ft. To help with streetability, the massive intake valves were reduced from 2.23 to 2.19in.

Buyers were also spoilt for choice when it came to exterior colours in 1970 with 13 colour options as well as special order colours. You could choose from 18 different vinyl or cloth schemes, but everyone knows that real race cars have your basic black vinyl interior, and that’s the box most people ticked.

The competition suspension package was tweaked slightly and a 0.5in rear sway bar was added. While every 1969 Boss 302 rolled out on flash-looking Magnum 500 wheels, standard wheels for 1970 were 15×7 steelies with dog-dish hubcaps and trim rings. The same F60-15 tyres were fitted no matter which wheels were chosen.

The 1970 racing season ended in success with the Fords beating out AMC, and Chevrolet in third. It was no easy task though as the heavy support received from on high in the form of Bunkie Knudsen had ended in August 1969 when he was fired and replaced by Lee Iacocca. Iacocca didn’t have high-octane fuel running through his veins and the racing budget was cut by 75 per cent – ironic considering his involvement in promoting the sportiness of the Mustang when it was first released.

Before the end of 1970 Ford would pull factory support from all competitions, so it was left to privateers to fly the flag for the Blue Oval. In reality, automotive safety and emissions were starting to become a big issue and the massive sums of money spent on motor racing didn’t impress the shiny bums who make the rules.

On the track most teams ran 1970 cars, but on the street the Boss would live on for another year – enter the Boss 351.

BOSS OZ

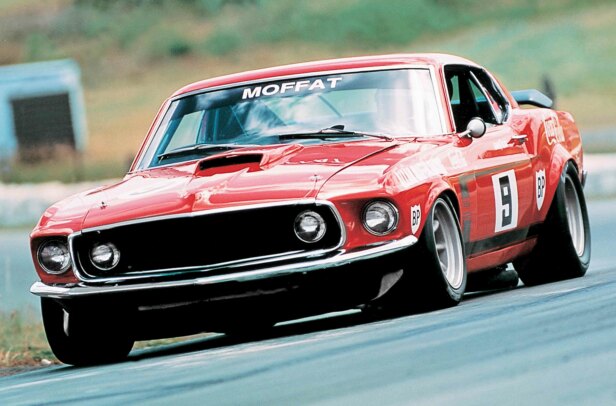

FOR Aussie Mustang and Ford fans, there is no greater car than Allan Moffat’s ’69 Boss 302. One of the three cars built by Bud Moore Racing using the blueprints developed by Kar Kraft, Moffat’s car had an amazing career here from 1969 to 1974, winning 101 of its 151 races.

Painted in the bright red of sponsor Coca-Cola and hunkered down over its race-bred suspension, its exaggerated rake made even more menacing by the wedge section removed from the front clip, the Mustang must have looked like something from outer space.

Although it never won the Touring Car Championship, its battles with Pete Geoghan’s Super Falcon, Bob Jane’s ZL1 Camaro and Norm Beechey’s Monaro are the stuff of legend. It was the car that dragged racing away from backyard engineering and gave it its first shot of full-time professionalism.

Its appearance and performance had a profound effect on the owner of the cars on these pages, when as a young man in 1972 he saw the Mustang racing at Wanneroo. “He lapped the field. I was young, had too many beers while watching and thought, I gotta have one of those. There were no Bosses in WA, but I found one in Sydney in ’83,” James recalls.

It seems when the Mustang bug bites, it bites hard. Not only does James own the four Boss Mustangs on these pages, he’s also got a couple of Shelbys and the odd Cobra Jet tucked away – but that’s another story.

Another Boss 302 that tore the competition apart was Jim Richards’ Sidchrome-sponsored car. Bought as a road car in 1972 it was developed into a race car by a Kiwi called Murray Bunn. Featuring a highly modified 351 Clevo and some super-wide wheels also developed by Bunn, Richards took out the ’72/’73 NZ saloon car title. Richards and his team figured they were good enough to take on the Aussies, so they jumped across the Tasman and he obviously did all right, because he’s still here.

The late Frank Gardner also campaigned a Boss 302 in Europe. It was an ex-Bud Moore car that was updated to 1970 sheetmetal and then tweaked to suit European rules, which were a bit tighter than the US Trans-Am series. It didn’t matter, because the car went on to great success in the UK and South Africa before it made its way to Australia. Sadly, after never getting a scratch on it while racing, the car was heavily damaged by its shipping company, and although repaired, it ended up being written off in a towing accident.

A little-known Aussie – although he was born in Austria – by the name of Horst Kwech raced in the US Trans Am series, most often in an Alfa Romeo, but also in the Shelby Racing #2 car on a few occasions. One thing is for sure, when Ford wanted to go racing, it didn’t muck around.

BOSS 351

WITHOUT the racing pedigree of its older brothers, the Boss 351 never garnered the same street cred or mystique that surrounds the Boss 302. Although he had been gone for more than a year, Knudsen had been at Ford when the 1971 designs were at a stage where he could put his stamp on them.

The ’71 Boss 351 was the last of the breed, and as a street car, possibly the best one. But with no racing pedigree it doesn’t command the loyalty the 302s have

The Mustang was heading for a longer, lower and wider design, which not surprisingly made the car heavier. The Boss 351 weighed in at some 300lb (136kg) heavier than the Boss 302, so it’s just as well it had some extra muscle to move it along.

While Ford didn’t have to play any homologation games in 1971 due to its withdrawal from motorsport, the new 351 Cleveland was given some special treatment so it could live up to the Boss name. The block featured four-bolt mains and although the crank was cast and not forged, it was Brinell tested. The forged rods were shot peened and magnafluxed and the forged pistons created a stout 11.1:1 compression ratio.

The heads were essentially the same as those on the Boss 302, so Ford knew they worked a treat and the Holley was dropped for a 750cfm Autolite carb. A cranky solid cam was also slipped in, which gave 491 thou lift at 324deg duration. The bonnet featured air intakes that will look decidedly familiar to all you XB GT owners out there – with one small difference – they actually worked, feeding cool refreshing air into the carb. All up this added up to 330hp and a stump-pulling 380lb-ft of torque at only 3400rpm – way up on the 290lb-ft at 4300rpm of the Boss 302.

As with the ’69 and ’70 cars, you could only order the Boss 351 with a wide-ratio top loader fitted with a Hurst shifter. The same nodular-iron, 31-spline 3.91-geared nine-inch diff was tucked under the bum and the competition suspension package once again found its way under the car, still featuring the staggered rear shocks and beefy sway bars front and rear, measuring 0.88in and 0.63in respectively.

Considering the extra weight and the fact that 58 per cent of it was over the front wheels, the Boss 351 actually handled the twisty stuff pretty well – remembering this was 1970s America and most people were used to driving around in something resembling a lounge room on wheels.

An engine that will look familiar to many readers. The Boss 351 used a Cleveland block as opposed to the earlier Windsor design. The engine was fed cool air from functional bonnet scoops that look just like those on an XB Falcon. You wonder why Ford Australia didn’t do the same

Externally the styling was low key and subtle, more akin to the Boss 429 with its discreet badging and simple stripe kit. Still, with only 1806 built, and capable of 13-second quarter-mile times, the Boss 351 is still a very rare and desirable car even if it never really made a name for itself on the track. It was also the last of the Boss Mustangs and although the shape lived on until 1973, the oil crisis and horrible smog equipment strangled any hope of continuing the legend.

Comments