IT WAS 1976 and pre-production of Mad Max had begun. Byron Kennedy and George Miller had budgeted $350,000 for their film, including a mere $20,000 for props and vehicles, and a paltry $5000 to keep those vehicles on the road. The climax of the film was to feature a super-hot pursuit car, known at this point only as the Pursuit Special.

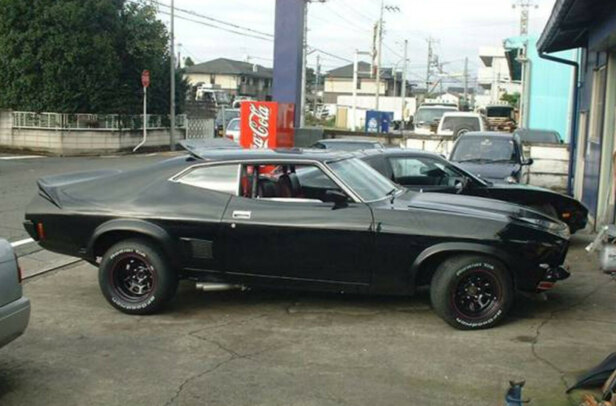

A year later, funding in hand, work commenced on the cars. The initial designs for the feature car were highly stylised and futuristic, with spoilers to the roof and boot, flares on the wheel arches, and a modified front end. The overall design looked not unlike a modified Mustang, and for a brief moment that is what Max was going to drive.

Murray Smith — one of the film’s mechanics — remembers his opinion of that suggestion: “You’ll be flat-knackered trying to get parts for the thing!”

He was right; this wasn’t a show car but a fully functional film car that would be driven hard and used for stunts. It was almost certain that repairs would be required and the foreign Mustang would be too much for this low-budget production.

The guys were confident they could instead modify and maintain some Aussie Fords to fit the bill. It was the height of the van craze and they’d seen Monza fronts for Holdens that looked like they could be modified to fit the Ford and achieve the look they were after.

Next stop was a car auction in Frankston, Vic. Three cars were purchased for less than $20,000 — two ex-police V8 XB sedans and a white V8 XB GT coupe that’d been repossessed. The sedans became Big Boppa and Max’s Yellow Interceptor, while the GT would become the Last of the V8 Interceptors.

The coupe was to get a Monza front but it turned out that similar fronts were being built to suit Fords by Peter Arcadipane, a former Ford stylist. His work on the Concorde show van caught Ray Beckerley’s eye. Ray worked at Graf-X International and had been contracted to customise cars and bikes for the film.

Lindsay Houston (now of LDI Kustoms) was working with Graf-X, which did a lot of van interiors, including 70s show vans Tangerine Dream and Midnight Madness.

“Mad Max was just another job. It was no big deal, it was no more important than anything else we were doing at the time.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by many who worked on the film. By the same token it was no less important either and the hard work these guys put in is a large part of what makes the film what it is.

The coupe was one of the first creations. First the blower was fitted, simply mounted on top of the air cleaner. The fibreglass nose was fitted in Peter Arcadipane’s workshop while the spoilers were the work of Errol Platt at Purvis Fibreglass Products: “They were actually ripped off Bob Jane’s Monaro Sports Sedan. It didn’t take a lot to make them fit, just a little bit of grinding, some Sikaflex and bog and all of a sudden, there’s your spoiler,” Ray says. “One of my little sick fantasies. I looked at the car from side-on and thought it needed a wing on the roof as well. Aerodynamically it was horrible.

“The flares were done by a bloke called Rod Smyth and his brother. Rod had just gone out on his own. I’d known him a long time as he was a truck painter and I’m a signwriter by trade.”

When it came to the paint scheme, Ray was given a brief by the movie’s art director, Jon Dowding, that it had to be black on black.

“I took that to mean gloss and matt, which is the way it finished up.” Similar to the factory XB GT design, it differs in swooping up from the rear wheel arch to follow the line of the rear spoiler.

Filming finished in 1978 and the movie was ready for release in Australia by April ’79. It was an instant hit, far exceeding everyone’s expectations. Worldwide it met with much the same reception. The exotic car had fans talking and featured heavily in promotional artwork, along with the ‘Interceptor’ tag, which became it’s official title for fans worldwide.

Following the completion of filming the producers had run out of money and put the car up for sale — for $7500 it could have been yours — but there were no takers. Instead it went to mechanic Murray Smith as settlement for unpaid work. With the success the film achieved on release, the producers decided to buy the car back, for a sequel.

This time the budget was much more generous and they built a double, to give them more flexibility. The original GT was retained for most of the close-up shots; the double was a much rougher Fairmont — an automatic! — used for most of the wide shots and stunt work.

Much to the horror of fans, the script called for the car’s death in a crash and burn sequence, and that’s exactly what they did — to the double. They rolled the car down the embankment several times until they got the shots they were after, leaving it genuinely as battered as it looks on film. One final explosion was then set off to burn it to the ground.

Through all this, the original GT survived, largely intact. At the end of the sequel it was again put up for sale with the other props and vehicles. Even a good coupe wasn’t bringing too much money back then and this one was badly beaten up — the original GT front was missing, the boot had been cut out to install the fuel tanks, and the interior had been stripped.

Just the same, the new owner didn’t have the heart to strip it down and it became a curiosity. It eventually moved to another owner, near Adelaide, where it sat until it was rediscovered by Bob Fursenko. He restored the car and put it on display for the fans. During the following years, the car toured the country, with plenty lining up to have their photo taken sitting in the Mad Max Interceptor.

However, by the early 1990s Mad Max hysteria had passed and the car was on display in the Birdwood Motor Museum in Adelaide. Bob decided he’d done everything he wanted with the car and put it up for sale. Yet again there were no takers.

Finally car collector Peter Nelson heard of its whereabouts. He runs the Cars Of The Stars Motor Museum in the UK, and has an extensive collection of movie cars. He’d long had the Interceptor high on his wish-list and at a car rally in Germany in 1992 he heard it was available. After contacting Bob and verifying that the car was the real deal, he shipped it to the UK.

It now takes pride of place in Peter’s museum, and people travel from around the world to see it. To Peter, the Interceptor is much more than just another film car.

“This car was the most important car, I felt, to a country. Some people would say Mad Max is probably one of the most important Australian films.” Of course, the car also appeals to Peter for the same reasons as the rest of us: “I like the styling. It suits the film perfectly, and it made a great presence within the film.”

Peter has hinted that if the car ever leaves his museum, he’d like to see it come back to Australia, though he’s in no hurry to part with it. And despite its poor history in the market place, we reckon you’d need to write a fairly large cheque these days.

Since the story above was originally published, the car has moved to the Miami Auto Museum in Florida. And is now up for sale, full story here.

Comments