FEW MEN know more about Holden’s iconic 308 cubic inch V8 race engine than legendary builders Ian Tate and Neill ‘Part’ Burns. Both were at the forefront of 308 development in the 70s and continue to bolt together tough race engines today, Burns for V8 Supercar team Tasman Motorsport and Tate with his own specialist business. And they both have a common denominator, Peter Brock, who raced to victory many times powered by engines built by these two gurus.

First published in the July 2006 issue of Street Machine. Peter Bateman & Philip Morris Archives

The gorgeous engine you see here is Brock’s 1979 Bathurst-winning A9X donk, five litres of fame that enabled Brock to win that race by an unheard of and never repeated six laps, and break the lap record on the last lap. This engine and the car it ran in are now a revered part of the Bowden collection.

Both Tate and Burns have good memories of these magical motors but Burns was the man who built this one. Burns is not particularly sentimental; to him an engine is just a conglomeration of pieces that bolt together in a set formula, but he has fond memories of this particular example.

Burns had been working with another touring car legend, team manager John Sheppard, since 1972 on cars like the Norm Beechey Monaro, but when Sheppard took over the Holden Dealer team from Harry Firth in 1978, Burns went along for the ride and stayed until 1985, when he joined Larry Perkins.

Tate started at Firth’s historic Hawthorn, Melbourne workshop in 1963, working on cars as diverse as Cortina GT500s, Ford’s London-Sydney Marathon GTs and the ’67 Bathurst-winning Falcon GT. Firth set up the Holden Dealer Team in 1974 but Tate left in 1976 to set up his workshop. Tate eventually bought Firth’s workshop and was there for years, finally selling it in 2000 and setting up shop in Nunawading, Melbourne.

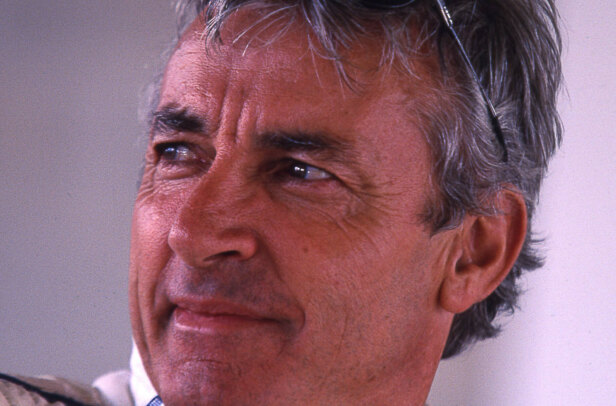

Brock on the Bathurst podium in 1979, with Jim Richards to the far right

The A9X engine was a development of the L34 Torana unit but in 1979 it was still a fairly stock item, with standard inlet manifold, heads, pistons, rods and crank; only camshafts and exhausts were free. The compression ratio was 10.5:1 and strictly enforced. Teams could machine and clean up heads, block and deck heights.

“We’d basically just blueprint them; there was nothing trick about it,” Burns recalls, adding that he was the engine department in those days. “You couldn’t do much; you could cheat but you’d get caught, just like today.”

Tate expands on this.

“The engine was virtually the same from the L34 to the A9X in ’79, but they were developed more and more as time went on,” Tate remembers. “The only changes allowed were camshaft design and exhaust systems.”

With so few modifications allowed, scrutineering was very strict in the 70s, Tate says. “Shit yeah, CAMS scrutineers used to seal the engines and pull them apart later. Don’t forget, old Harry Firth was chief scrutineer in the late 70s then John Sheppard was technical officer and it would have been pretty hard to get much past those blokes. Compression was controlled by deck heights and combustion chamber volume and compression ratio and bore and stroke were governed very strictly.”

The engine as it is now. David Bowden bought it in 2005 from Terry Hewitt. Hewitt was an HDT member who’d bought it – along with statutory declarations signed by Brock, Sheppard and Tate to say it was the genuine article – from the team at the time. He mentioned it to the Bowdens, who he knew had the original ’79 Bathurst-winning A9X car. “He wanted us to have it,” says Chris. “He wanted it to be back with the car.” Together, the car and engine make up part of the Bowden’s private collection which includes 90 cars. For more, check out www.bowdensown.com

By today’s standards, the A9X engine wasn’t a big mumbo motor, producing about the same amount of power as an LS2-powered HSV ClubSport – around 297 kilowatts – but for the time almost 400hp was the duck’s guts.

“We had our own dyno and the engines used to make just on 400 horsepower and around 380 foot pounds of torque,” Burn says, of his class-leading engines. Tate reckons his were right up there too, although he had a smaller development budget. “It depends on the dyno, my engines made about 393-395hp in the end; some people quoted a lot more,” he says. “To keep pace with HDT, I got all my customers to tip in money and I got some exhaust systems made, then spent a week on the dyno and everyone got the same engine. We developed a pretty good package, the equal of anyone’s, and Bob Morris’ car was as quick as Brock’s on most circuits.”

The 308 is a classically handsome engine, simple in design and appearance, with a twin Weber 48IDF carburettor set-up with two ram trumpets per carbie, mounted across the engine in an east-west configuration.

The twin Weber was regarded to be largely responsible for the 308’s impressive performance. The trumpets were added and angled to increase performance

“Twin Webers was the universal set-up in the finish, they were the bees knees,” Tate says. “They were easy to keep in tune, you’d bore the top of the carbie out and put little trumpets on them and if you fiddled with them you certainly got more power. We’d put spacers between the carbies and the manifold and use different length trumpets – you were on the go all the time, especially with exhaust systems. We had two-inch extensions for the exhausts and every time you were on the dyno, you’d play with the length of the exhaust to fine-tune them.”

For all their apparent simplicity, though, the A9X engine wasn’t 100 per cent bulletproof; it had its weak links, mostly parts that couldn’t be changed for more high-performance examples under the rules.

“It wasn’t brain surgeon work doing those things,” Burns laughs. “It used to take us about a week to assemble one, by the time you got everything measured up and machined. But they weren’t unbreakable and were limited to 6800 revs. Other teams used to claim they’d run to 7400 but that was bullshit; we’d always run them to six-eight, that was a Sheppo [John Sheppard] stipulation. And if you didn’t do that, Sheppo would beat you to death. The rods and the crank were the weak links and you’d replace them every 1500 kilometres as a precaution.” Tate agrees with this assessment.

“The crankshafts were the problem before GM built some decent cranks, they cracked. Bathurst was (a total) of 620 miles plus practice, so the engines would do 700 miles easy then we’d pull them apart and crack test them. Later on Harrop steel cranks were allowed but a lot guys couldn’t afford them.

“We used to crack test and replace the rods frequently. The Achilles heel on the early L34s and A9Xs was the rotten bloody valve springs we had to use, they were the most unreliable thing ever and caused a lot of engine failures. I’d X-ray and crack-test them, but for no reason they would break half way through a race and drop a valve through a piston; they

were dreadful things.

“When valve springs became free we changed to Iskenderian, which changed the whole life of the engine. We only revved engines to 6500; there was no power after that. The L34 manifold was terrible. Manifolds in the mid-80s were worth 20hp more over the L34, which was stock standard apart from the inlet holes, which were milled out to two oblong slots by Yella Terra.

“We weren’t allowed to port the heads in those days, you had to use the heads as they came from Yella Terra. You were allowed to clean them up because some heads were (better) finished more than others, so you’d get stuck into them with the grinder. Some blokes took that to the limit and ported them extensively, some didn’t. There were gains to be made in finishing the heads; you could do what you wanted but that’s why CAMS cracked the shits. They said they’d never let a hand-finished head through again, because it was very hard for them to control how much porting was done.”

For Bathurst, HDT took an engine for each car and a single spare 308, Burns says. “In those days we never changed engines once practice started. That was one of Sheppo’s philosophies: if you have to change engines at the race meeting, you might as well not go. He was pretty stringent about that, if you couldn’t get the thing happening in the workshop you may as well not go to the race meeting. During the race we just sat back and waited. At half race distance we’d probably slam a litre of oil in it; that was about the norm in those days.”

Tate’s methodology was similar. “I used most of the engines I built for the top teams during the year then pulled them apart, lightly honed the bores, put new sets of rings in and reassembled them for Bathurst and they would be used all Saturday and Sunday,” he says.

Peter Janson (left) was second in the race and apparently amused by the attention Brock received. Well, he did just smash Alan Moffat’s lap record on his final circuit

Tate still has a soft spot for the venerable 308. “It did a fantastic job in motorsport from ’74 till 1987,” he says. “But the A9X was a fantastic handling car. It was reasonably aerodynamic, it had four-wheel disc brakes, the T-10 gearbox and a Salisbury rear-end and it was a pretty strong car. Put decent rubber on it and it had a lot of grip. Brock will still tell you that it would qualify for Bathurst now.”

Burns is a little less misty-eyed over the A9X engine. “It was just another engine in just another race,” he shrugs, “but from what I can remember, we had a pretty good party after Bathurst in ’79.”

Both, though, are adamant about Brock’s ability to get the best out of their engines and any car he raced, Burns denying his engines were jets. “Nah, it was Brock, really. The engines were nothing special; it was just a combination of engine, driver and chassis. It’s the same today. They all piss and moan about engines but if you have everything from the driver’s attitude to the tyre pressures right, you’ll go quick, even if the engine is a piece of shit.” Tate is still a big Brock fan to this day.

“In those days you had to go out and pace yourself for 600 miles at Bathurst,” Tate emphasises. “The smart guys could get their cars home, but Brock could get a car home and win a race at the same time. That was why he was head and shoulders above everyone else; he had the ability to coax a car home.” And Tate has a contentious example of that, directly from that amazing 1979 Great Race.

“I was with Peter Janson and he finished second, six laps behind Brock. I went up to congratulate Brock after the race and he said, ‘Oh mate, I was lucky today, she’s got no oil in it.’ I said ‘Bullshit!’ but we went to see the car on the Monday and there was nothing on the dipstick! It had oil but not much, it was obviously getting a lot of oil surge.

“That prick got that car home and I couldn’t believe it. He could drive a car home with three wheels; he was amazing that way. Anyone else would have burned the bearings out, but not Brock, he could get the most out of a car.”

Burns – and he built the engine, remember – disputes Tate’s rose-coloured story. “That’s not true, Brock always extends the truth,” Burns laughs. “You can’t set the fastest lap of a 500-mile race on the last lap with no oil in the engine; that’s just bullshit. It was a good story at the time so they ran with it.”

The 70s was a decade that cemented reputations and rewrote Australian racing history – tall tales or not – but one thing is for sure, that Peter Brock A9X engine belongs in the V8 hall of fame.

BROCKY’S MOUNTAIN HIGH

ANY CAR and engine that allows a driver to win a 1000-km race by six laps and set the lap record on the final lap must hold a special place in his heart and Peter Brock’s 1979 A9X and its trusty 308 is such a combo, as he recalls.

“Neill Burns built the engine; he designed it all, it was his development and John Sheppard probably had a bit of influence in the carburetion. There was a lot to be gained in the angling of the Webers to give you airflow under the bonnet and the length of the manifold was another issue too. There was a fair bit of thinking into the carbie with its short ram tube arrangement. The guys made the exhaust in-house in those days, too.

“That engine wasn’t even vaguely a racing engine when you think about it, it was just a standard engine that had big valves, but because you could fit nice carburetion and exhaust you could get some power out of it. We only revved them to six-eight, that’s all we ever went to. Some people fitted better crankshafts and conrods, which allowed them to rev to over 7000rpm but that was illegal. Being the works team we had to be squeaky clean.”

What about Tate’s recollection about the engine having little oil in it after the race?

“I think Ian’s memory is a little bit hazy on that one,” Brock laughs. “It wouldn’t have been anything to do with the engine being depleted of oil, it would have been more to do with the engine’s design and not requiring a full sump. There were some theories that to overcome surge you filled them up with a lot of oil, but that engine didn’t need that because it didn’t burn oil and it had a good sump design; it didn’t need over filling. The bottom line is its oil level wasn’t high because it didn’t need to be.”

Comments