OPERATING under the E.Black Design Co banner, Eric Black is one of the most talented vintage automotive designers of today. The quality of his work has seen him team up with huge industry names like Roy Brizio, Pinkee’s Rod Shop, Austin Speed Shop, Johnson’s Hot Rods, ICON 4×4 – the list goes on. Eric is based in Portland, Oregon, but we met up with him a few hours away in Hood River at his home away from home to chat about everything from vintage fishing reels and material transitions to collecting stone chips on the highway.

This article on Eric Black was first published in Street Machine’s Hot Rod #19 magazine, 2018

Your work exhibits such a natural understanding of car design and mechanics – did you grow up around cars?

As a kid I was fascinated with the TV show Movin’ On about truck drivers, so I started drawing semi-trucks and eventually moved on to drawing hot rods, 4x4s and old trucks. My family was not into cars, and growing up in Wyoming I was isolated from a lot of car culture. Because of that I was heavily influenced by what I saw in magazines – and not necessarily in a good way! [laughs] Magazines in the 80s – well, you know what those were like.

Did that early influence carry on all the way through life?

When I got older I thought that if you were in automotive design it was only for new stuff – concept cars, futuristic models – but I was never into that. I didn’t think I could make it a career until I realised later on that people like Thom Taylor or Steve Sanford, who I’d seen in the magazines, were making a living off it. I steered away from automotive initially and went to architecture, where I received my formal training.

Would it be a safe guess to say you’re influenced by or collect vintage things?

All that dumb stuff? [laughs] Yeah, of course! I’m really drawn to typology – I love seeing that there are thousands of ways to solve a problem. If I had all the space in the world I’d own every beautiful chair. There are countless ways to sit your arse on something and a few of those are some of the most beautiful pieces of industrial design you’ll ever see!

I’m into things I can afford, so I have silly stuff like camping water jugs. I have about 100 of those actually. All they’re doing is holding water, but every one is unique, and it’s cool to see them all at once. Vintage fishing reels is my recent collection – ones from the 40s to the 70s – and it’s cool to see the progression of design and technology over time. They’re dirt cheap and it’s something different.

How else do you find influences and inspiration?

Often I’ll step completely away from the car world. Nothing translates perfectly, but if I can take away even some tiny element I can expand it for a project. A lot of architectural thinking comes into what I do, too. Eames certainly, Mies Van Der Rohe. Louis Kahn was really into understanding materials when people are using them. He’d have incredibly Brutalist architecture but he’d make a handrail out of wood, because that’s what you’d be touching. I like ideas like that, they’re pragmatic, and I think of cars in the same way sometimes.

Would you say you have a certain approach or philosophy to your designs?

My take with custom cars is that I know there are thousands of ways to design an interior or whatever else, and it eases my mind to say I’m just making one of those thousands. If you ask me to do the same job a year from now, even five weeks from now, it’s going to look different.

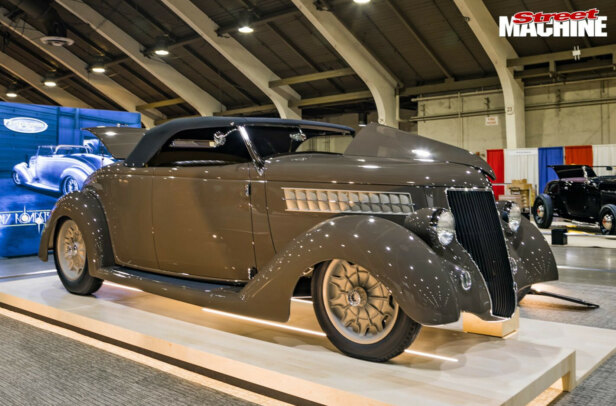

The Mulholland Speedster is a 1936 Packard owned by Washingtonian Bruce Wanta, and built by Troy Ladd and the team at Hollywood Hot Rods. Eric played a major role in the design of the car, and it took home the 2017 America’s Most Beautiful Roadster award. “When it started, it was meant to be a Ford with Packard influence, but it became so much so that I just said: ‘Why don’t you do a Packard instead?’” Eric says. “Builder Troy and I came to that conclusion at about the same time.”

In my mind it’s a matter of customising cars to take them away from their original identity, but if you look at the cars formally, they’re all very similar. I’m influenced by Bugattis when I’m working on Fords, and if I was working on a Bugatti I’d probably be influenced by a Ford. Take any ‘grand’ 30s car – Packard, Duesenberg, Delahaye – and if you squint your eyes it’s not too much of a stretch from any ‘lesser’ car like a Ford or Dodge. That elegance and timelessness comes down to proportion, scale, small details, and I try to consider those in my approach.

Eric was asked to design the interior for Austin Speed Shop’s AMBR 2017 contender, the Hill Country Flyer. “I was trying to think through the pragmatics of how you use an interior, so a lot of the details around the edges of the doors, things like that,” Eric says. “Your feet always hit the kick panels, so how can we resolve that through design?”

Your renderings have such accuracy and show a high level of builder’s knowledge, but you’re not a car builder.

I’m a hack! [laughs] No, I will say I’m limited in my abilities, but I’ve had a lot of projects where I’ve worked very close with fabricators, and I understand what is feasible and what isn’t. Dimensions, proportions and always striving for accuracy play a large role in my work. I always think through the functionality and ergonomics, so for example if we’re doing a radical chop, I’ll consider how the person will actually sit inside the car. Sure, I can make something look cool, but if it doesn’t function well, why do it?

How long have you been doing automotive design?

I started it full-time in 2012, though I’d done it as a paid hobby for about 10 years prior. I lucked out because I was able to ease into it and not have to dive in, being forced to rely on it as sole income. It’s lucky to have worked out this way – it certainly wasn’t the plan.

What is the process behind creating a rendering?

I use a Wacom Cintiq monitor, which allows me to hand-draw on the computer, using various sketching and rendering programs. I use a lot of layers and build them to allow for flexibility – it’s easier to manipulate and test ideas and change small things when working with builders. I have a lot of respect for people that still do it on paper, but I just chose a different approach. To think about doing what I do, but on paper – I mean it’s possible, but sounds painful! [laughs]

How do you come up with such perfect lighting and detail in your renderings?

When I’m looking at a car, those are the things that grab my attention – reflections, how light hits angles, things you might not realise you’re seeing, but they’re important. Say you look at any fendered car, you’re going to see the reflection of the hood in the front fender, and in that reflection you’ll see the louvres too, so I’ll capture that. Little things like that take a long time to get right, but they’re very important because that’s what’ll happen in real life.

I’m drawn to a lot of indoor and studio photography, thinking about clean ways to display car ideas. I am aware that the car will look different outdoors and, hopefully, driving, but it’s important to pick a style and run with it.

Speaking of driving, you’re an advocate for stacking up road miles.

The driving aspect is extremely important – so many of these cars get built to a point where people are afraid to touch them. I’m really drawn to cars that get used. Darryl Hollenbeck is a great example because [his AMBR-winning ’32 roadster] is a car that you’re going to drive often, and when things happen, you just deal with them – you let it age gracefully.

I had a conversation with a client the other day about understanding what you need to be comfortable with. If you want the car to be a daily driver, but you want special-mix paint and multiple plating options, when you get your first road chip are you going to freak out or just be cool?

Personally I’m a slob [laughs], so I don’t know if I could ever have a completely dialled car. I don’t have the personality for it – ‘cobbler’s shoes’ mentality. Some day I do want to finish my roadster, though.

Eric’s Model A was built by close friend Dave Lyon in ’85 and has been driven hard by both Dave and Eric, who came into ownership himself about five years ago. It runs a 348-cube W-motor fed by 3x2s, but a 409 and five-speed are on the way. “It’s changed engines and transmissions over the years, but it’s also gone through four different tops. Each one gets shorter and shorter! Dave is smaller than I am so he never complains!” Eric laughs

Your black Model A?

I’d love to finish it and try to be okay with it when it gets chipped [laughs]. My friend Dave Lyon built it in 1985 out of an old survivor from the Auburn, California area. Underneath it’s basically an 80s street rod; it has a straight axle but four-bar front and rear, coil-overs, all that stuff, though I’ve changed it up to give it a bit of an earlier period look. It’s running a warmed-over 348ci Chevy W-motor, 3x2s and 200R4 trans. I’m not a fan of auto ’boxes, so I want to replace it with a five-speed. I’m also in the middle of rebuilding a 409 for it, which is what Dave always wanted to run. He’s my best friend and very dear to me, so this car is very special.

How’s the odometer looking?

The car has over 100,000 miles on it since Dave built it – it’s been all over the country; Texas, Kentucky, wherever. I’m guessing I’ve done 16,000 miles myself in five years or so. I drive the hell out of that car and I’m pretty hard on it, but it’s a great driver. We do long road trips with my kids and dog as often as we can.

Builder Alan Johnson had won a Ridler award already when George Poteet and the crew decided to pick the award event to debut the new sedan. The project stalled in 2014 after Poteet had his infamous 370mph Bonneville crash, but Eric was called in when things ramped up again in 2015. “When all was said and done, everyone had put 100 per cent into it, and probably didn’t get back what they put in,” he muses. “It wasn’t about that, though. It was about trying to make the best damn ’32 we could come up with.”

Is there a recent project that stands out to you?

The Poteet sedan. Working with Alan Johnson was fantastic. I’d always admired his work and I was amazed he put as much trust in me as he did. He’d call me pretty late at night and we’d talk about anything – design ideas, material transitions, you name it – and it wasn’t time I was billing, just time spent talking about the car. It was a very ambitious project and I learned a lot about his attention to detail. I remember he called me up one time and said: “I want to design a bucket for the back of the gauges” and I was like: “Holy crap!” That’s the level he was at. I got a good education out of that car and gained a friend in Alan; it means a lot to me.

Anything new in the works? What’s next?

There’s a lot of things I can’t talk about unfortunately, but I often find myself thinking about how I’m gaining a voice within the industry, and how I can use it positively. I don’t think the industry is pushing enough anymore – we’re in a comfort zone. I want the industry to survive, and I want to use my abilities to get it thriving by adding more money into it for the builders, creating new projects and getting more people involved. Jonathan Ward from ICON really agrees with that concept too. We just want to create cool stuff, and do what we love to do. I have friends that are builders, and not many of them make huge amounts of money, so I always think there has to be a way for me to help.

Comments