MAKING a new race car run the way you want is never easy, and new engines and experimentation only add to the complexity.

Add to that the traumatic sudden loss of your race team’s inspirational leader, and the hurdles seem even higher. So it came as little surprise that the debut of the Sainty team’s new Top Fuel car at Sydney Dragway in early November was fraught with difficulties, with the crew still deeply emotional from their chief’s funeral the previous day.

In life, Stan Sainty seemed unconquerable. He was big and strong, with the hands of a man who made his living by hard work. He was quiet, generous, uncomplicated; a humble figure who was just doing what he loved. Over the years he had pushed, cajoled, dragged, finessed and bullied his Top Fuel race engine from a seemingly crazy concept – that you could design and build a world-beating mill from scratch in a suburban workshop – to a reality that, in the eyes of the NHRA’s technical team, needed to be banned almost as soon as it showed promise. This thing looked too good to be out of the control of their best race teams.

The day after Stan’s funeral was the AC Delco East Coast Thunder event at Sydney Dragway, where the team paid tribute to its fallen figurehead with special livery on its new car. The track held a minute’s silence to honour the great man’s contribution to the sport

The Sainty race team was never a major player in the sense of setting records or winning major events, though they enjoyed success with some major runner-up spots and a third-place finish in the 2004-05 Top Fuel Championships. They lacked the funding of some other race teams, but their homespun family-based operation was also never to be taken lightly and was always on the verge of suddenly living up to its promise.

So, who was Stan Sainty?

Born 17 April, 1946 in Western Sydney to an engineer father, Stan showed an early tendency for breaking all the rules, along with a capacity for imaginative problem-solving. Even before he could talk fluently, he told his parents that the “clock” had stopped ticking, and they subsequently discovered that his attempts to modify the water meterin the front yard – with a hammer – had left it a wreck. Over the coming years he spent every possible hour turning billy carts into planes, pedal cars into boats, and pushbikes into submarines.

The Sainty’s first home-built Top Fuel dragster was based on a 300mm toy model that Terry owned. Piloted by Terry, the car debuted at Eastern Creek in 1992 and ended up running a best of 5.2sec over the quarter

An apprenticeship as a fitter-machinist was barely completed before he was called up for national service in 1967. He applied for the Royal Australian Electrical & Mechanical Engineers but was allotted to the catering corps. Two years later, his military service complete, Stan returned to civilian life as a fitter-machinist, moving through several employers.

Along the way he’d started a sideline business in engineering beneath the house that he and wife Marg had bought in Toongabbie. Over the years he added two big lathes, a crank grinder, a mill and a radial drill, all somehow fitted around support piers and flooring bearers. In 1984 he moved all the gear into a proper workshop at nearby Wentworthville, continuing to earn a regular wage at night as he supported his growing business. At the end of 1985 he converted it to a full-time occupation.

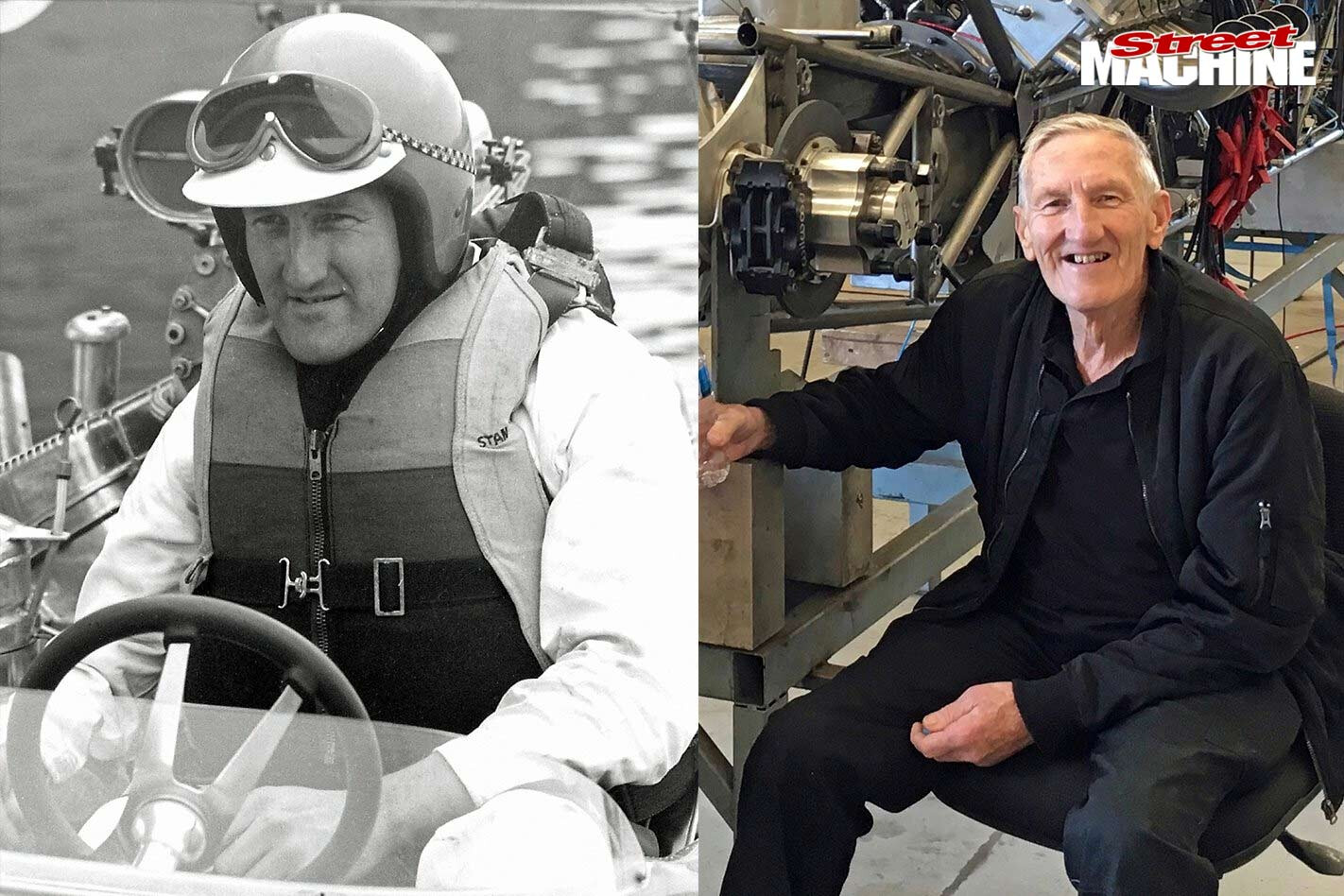

Stan gives his boat a bootful racing at Silverwater in 1977

After an early interest in dirt-track racing, Stan developed a love of water-skiing that evolved into a passion for fast boats. Soon he was driving very fast boats indeed, and finished up with blown alcohol engines at the pointy end of what was a very dangerous sport.

“It was a dangerous time to be racing boats,” says Stan’s younger brother Norm. “It was not a matter of if you would have a serious crash, it was a matter of when!”

In 1983, Stan and his boat Fallacy towed Christopher Massey to a world water-ski record of 230.26km/h. In the mid 1980s, Stan helped fellow boat racers John Bradley and Dave Newby develop an aluminium version of a big-block Chev, but found it wasn’t strong enough. Stan decided he should build an engine himself. It featured dual overhead cams, four valves per cylinder and eight-bolt mains. At 561 cubes, it made a ton of grunt on alcohol and put Stan up with the best in the game.

Stan’s son Terry inherited his father’s passion for tough engines and going fast, but he wasn’t keen on boat racing, preferring to get his kicks in a nine-second, 140mph street Commodore.

“Dad was getting pretty wary of drag boat racing too,” Terry explains. “In one year he had seven mates killed in the sport.”

When Eastern Creek Raceway opened for drag racing in 1991, Terry began to enthusiastically participate, and Stan figured this was a better area to engage his talents. The team bought a plastic model kit, scaled it up, and in 1992 built themselves their first dragster, with Terry as the driver.

On the quarter-mile, the OHC Chevy design just wasn’t a happy choice. It wouldn’t run well on nitro, and regularly burnt the heads between the exhaust valve seats. Simply replacing a head meant hours of work, mainly to re-time the belt-driven cams.

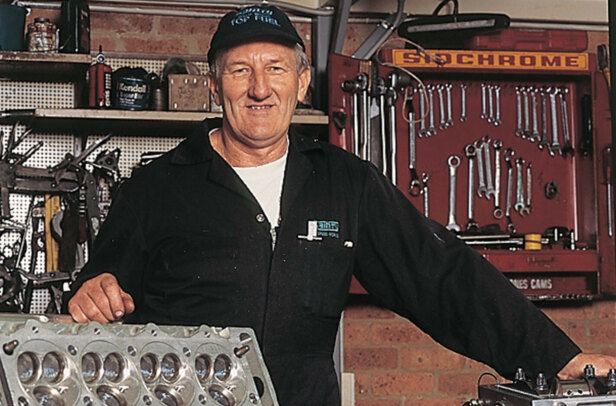

Sainty engine components were originally made by Stan in his home shed with not a single CNC device in sight!

Frustrated, Norm told Stan that they ought to be making a billet version of their motor, as billet material is seven times stronger than cast metal. To assuage any lingering doubts, he offered to pay for the materials and machining of the necessary parts. The original version of the motor, carved out of 6061 aircraft aluminium by the new CNC equipment that Stan had begun to buy in for his business, had a separate crank case and cylinder blocks, which bolted on (though these days they are one-piece creations). They solved the valve seat-burning problem by retaining the two inlet valves but switching to one large exhaust valve. The finished version – known as the Sainty Billet Three-Valve – became the first billet Top Fuel drag racing engine in the world.

All the equipment programming was done by Norm – clinically blind since his teenage years – and crew member Denis Maccan.

Stan developed his three-valve – two inlets and one exhaust – arrangement through trial and error while working on motors for himself as well as top team owners Graeme Cowin and Santo Rapisarda

During the planning phase the team contacted the NHRA in the USA to find out what they were permitted to do, so that if it all worked they might have a market there. They were told multi-valve heads, overhead cams and billet components were all fine.

The engine debuted in an all-new home-built car in 1995, and by 1997 had pushed its way to a reasonable 5.24-second best and won the Nitro Championships. The NHRA banned it within two weeks. ANDRA was more flexible, and over the coming years it ran times in the low-to-mid-fives and speeds around 270mph; good, but not great.

The third iteration of the bilet three-valve motor now runs on an American rail. “The new US car is lighter than our cars and probably better,” says Terry, whose PB ET is a 4.87@297mph, run in Perth 10 years ago. “I think there’s a PB in it. It’s just a matter of everything lining up on that particular run”

Seemingly the engine had some in-built problems in the 1990s and was known for a few pretty serious explosions, often on the step of the throttle in the burnout area or at the startline. But these never fazed Stan, who saw them as opportunities for parts to be re-engineered, strengthened and improved.

The engine is now on its third iteration and has begun to show real form. Recently at Willowbank it ran 260mph to half-track on the quarter-mile, with an early-lift 298mph top end. On another run, the front-wheel speed was 305mph before an early shut-off on a pass that scored 249mph at half-track. The best ET has been a 4.87 over the quarter, the bigger gains coming from re-timing of the cams.

Brothers Norm and Stan cut their racing teeth on the water, initially working with blown big-block Chev power. They made the switch to the dragstrip in 1992

The financial burden of drag racing has been a major hurdle for the Sainty team, so their cars have always been home-built. Only items they couldn’t make – tyres, wheels, wings, gauges – were bought. Everything else – from axles, hubs, chassis, clutches, fuel timing systems, and, of course, that famous donk – has been made in-house.

Stan formally retired and sold his workshop in 2016. He moved all the machinery and equipment to Terry and wife Belinda’s engineering business at Riverstone, where he could continue the development of his engine.

Stan’s 561-cube quad-cam engine first ran in his hydroplane drag boat called Fallacy. Stan had 18 racing boats, all called Fallacy, most of them painted yellow

The future became brighter with an offer of a US-built car from fellow racer Santo Rapisarda. It was lighter, with magnesium panels and all the latest touches throughout the chassis. Then came the bad news. Stan had been losing weight gradually, suffering with back pain and generally feeling unwell. A check-up by the family doctor produced a diagnosis of diabetes. “Get your diet fixed and take these pills and you’ll be okay,” he was told, but the problems didn’t go away. A second opinion a few months later returned a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and just a few months to live.

Everyone was stunned. The calmest of all seemed to be Stan. At 71, despite so-called retirement, he seemed unstoppable. He told his daughter Julie: “I’m not afraid to die. I just have so many things that I want to do.”

The announcement of Stan’s illness and the diagnosis on Facebook produced 131,764 viewers and 537 comments, every one of them replied to. Stan just couldn’t comprehend it. He thought he was just Stan,” Marg says.

His major immediate goal was making the East Coast Thunder Nationals in Sydney. It was to be the debut for the new car and all those new ideas. His beloved engine, he was sure, was about to live up to its promise. He failed to make that date with destiny by just under two weeks.

And yet there they were in the pits: son Terry, brother Norm, wife Marg, daughter Julie, and all the team, most of whom have been with the family since the boat racing days. They were still under a black cloud from the previous day’s funeral, but were determined to give it everything they had to get the car down the track, for Stan.

“Stan desperately wanted to be here for this meeting,” Marg said in Sydney. “He fought to the end, to the bitter end. I would have preferred to not be here right now, not after yesterday, but this is what Stan wanted.”

And what Stan wanted, Stan got. When asked what was behind Stan’s obsession with making his engine work, without exception everyone answered: “Determination.”

Tuner Dwayne Riley, a relative newcomer to the team, says he had never met anyone as determined as Stan: “He was a very stubborn man. Everyone knew him as a genial, friendly, generous guy, but he knew what he wanted and was determined to make it happen.”

“Stan said to me that his one wish was that his engine went on,” added Marg. “He told me: ‘I’d rather see the engine used and raced to its absolute limits; I don’t want it to become a coffee table or be thrown away as scrap.’”

“He didn’t see this as work,” Julie says. “He never saw it as work. It was his blinding passion. It was what he loved to do.”

Stan held in his head the secrets to the machining of these engines and he spent his last valuable weeks trying to pass on his skills and knowledge to Terry, himself a machinist.

“I’m not too sure about the future,” says Terry hesitantly. With eight complete motors and 17 finished blocks stockpiled at home, there is plenty in reserve, but still…

“It takes a lot of money to run these cars these days,” he continues. “Tyres used to cost $700 a pair, now they’re $3500, and they wear out more quickly. And that’s just one item.

“It will depend on what the crew wants to do. If they want this to go on, well, I suppose it will, somehow.

“The money issues aside, making this work will be a matter of teamwork, family and camaraderie, and they’re the factors we’ve always been strong on.”

Stan and his brother Norm were a tight team until the end. Norm has been legally blind since he was 18 but has an incredible propensity for numbers. “He’s pretty much a human calculator,” Terry says of his uncle

Stan Sainty was a genius, even if his methods were sometimes unorthodox. He had the same drive and determination as a Jack Brabham, but was just directing his efforts into a smaller pond, where the audience was measured in tens of thousands, not tens of millions. We’ll never see his ike again.

ROYAL TREATMENT

One of Stan Sainty’s proudest moments came in 2014 when the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee State Coach carried the monarch to the official opening of Britain’s Parliament.

The golden, jewel-encrusted carriage didn’t exactly make a record-breaking pass, but it did roll on wheels that were designed and built in the Sainty family’s workshop.

The wheels were made of aero-grade aluminium with chrome-moly reinforcing down the centre of each spoke, angled outwards to keep mud and other detritus away from the coach’s bodywork.

The project was the design of Sydney based craftsman W.J. ‘Jim’ Frecklington, who contracted the Saintys to undertake the work based on their skills in motor racing. The coach is reported to be the Royal Family’s favourite out of all their horse-drawn buggies.

SHOW MUST GO ON

Despite the Sainty team’s emotional investment in the East Coast Thunder Nationals, the event was a bust for them and their new Top Fuel car. The first attempted pass saw a fuel leak in front of the tyres, forcing Terry to shut-off.

Determined to carry the team name forward into the future is Stan’s wife Marg, son Terry, brother Norm and daughter Julie

The second qualifying round resulted in the throttle linkage breaking, while the third pass never even got to the burnout area as rain began to fall. As the car hadn’t completed a pass, it failed to make the eight-car field, but on the Saturday Terry sat strapped in the car as a one-minute’s silence was observed in Stan’s honour and a video presentation was played on the big screen.

Terry then fired the engine, staged, and cut a 0.86sec 60-foot launch, but then had to shut it down as he couldn’t see for the tears streaming from his eyes. It was a bitter end after an incredible effort just to be at the races, but the team plans to make a more measured attempt – tentatively scheduled for 21 January in Sydney – to see just what this new car can do.

Comments