Retired Holden engineer Warwick Bryce masterminded plenty of GM-H’s engine tech and made its V8s go. We caught up with him to get the lowdown on his career – and the truth about those ‘cop chips’.

This article was first published in the May 2020 issue of Street Machine

How did your tenure at Holden begin?

I started there in 1973 in what was called Experimental Engineering. There were body and wheels and shock absorbers and latches [departments], but my interest was in engines. I got my foot in the door, and once you’ve done that you look around and see where you can go. You follow your interest, and mine was in engines.

“It was a pile of bits, leftovers from another restoration,” Warwick says of his 1925 Chev jalopy. “I’d had Chev paddock bombs as a kid, so there was a connection there”

When did you begin on engines?

After about a year. We worked in areas known as ‘downstairs’ and ‘upstairs’. The design blokes were upstairs and they designed the parts to be tested and sent them downstairs to Experimental Engineering, where the team would decide what tests to do. I was on the six-cylinder. We had red motors then; it was the time of the HJ, and the LX Torana was also in the pipeline.

The 1970s, smog control – not a good time!

I was working on the carburettor and the ignition calibration. I was working on the first serious emissions version of the red motor [compliant for the new exhaust rules of the late 1970s]. It was already in production, but it needed a fair bit of fixing up for the HZ Holdens.

With the Holden V8 given a stay of execution, Warwick (left, pictured with fellow Holden’s Engine Company staffer Errol Croll) led the charge to create the VN V8

The later blue motor seemed to fix a lot of that.

Yes, next we worked on the blue motor with the 12-port head, the counterweighted crank and the two-barrel carby. I had a fair bit to do with it.

I was in Design by then, and we worked with the drawing office – the draughtsmen – to design such things as the inlet manifolds and the cylinder ports and so on. I worked on the cylinder heads and manifolds mainly.

The VL Group A benefited from the VN V8 development work, which was mostly done by the time the ‘Walky’ was approved by the top brass

This was the dawn of the ‘high-tech’ 1980s, too.

Fuel injection was starting to get popular in Europe, so we started thinking about it. It was a whole new world. We used a Bosch system, an analogue system. There was a lot of upgrading to take the extra power of the fuel injection. There was a new timing gear and a stainless head gasket. We also played around with better shapes for the valves and cleaned up the ports a bit and had a different cam. We ended up getting a lot more power from it. It was something like 25 per cent more!

Warwick and the crew experimented with a variety of induction set-ups for the VL Group A, including this configuration with twin plenum chambers feeding into a set of ram tubes

But the Nissan six replaced it.

Yes. With unleaded and GM USA going to a front-wheel-drive V6, we were left without an engine, so we looked around and found the Nissan. It was a good engine; it was a refined engine. Half the benefit was the transmission – it was an overdrive that we never had with the Holden gearboxes.

It helped with smoothness and with fuel economy. We did the vehicle integration, like making the fuel pumps work and keeping the engine cool by ensuring the airflow through the nose of the car – stuff like that. But the mechanicals came out of a box.

Warwick was heavily involved with the final iterations of the venerable Holden six: the blue motor with the 12-port head; and the black motor, which scored a new cam and timing gear, improved port work and optional Bosch-Jetronic injection – enough for 144hp

And the Aussie V8 soldiered on.

The V8 was going to die due to unleaded fuel. That campaign, where you could fill in a coupon and send it to Holden [the ‘V8s ’til ’98’ campaign co-ordinated by Street Machine and Wheels magazines], Holden got more than 15,000 coupons back. That’s why the V8 continued. With the V8 looking not dead, things became more serious. I wrote a proposal – just a handwritten letter – about a fuel-injected V8. I estimated performance and fuel consumption and what we’d have to change. I put that to management and they ummed and ahhed for a while and eventually said: “You can make two experimental ones to see how they go.” The main thing was rearranging the order of the inlet and exhaust valves so they were all the same.

We also did the new manifold.

Those heads were a big change to the V8.

That was for emissions. To get the best emissions from the car you need to have every cylinder getting the same amount of air and fuel. But [with the carburettor V8] half the cylinders were running richer and some were running too lean. Making them all the same means you can dial everything in, bang-on, for the best emissions.

Really? You didn’t do it for increased power?

[Laughs] Mate, there was an ulterior motive for all this. I should’ve got bloody sacked! We did a lot of work with the racing teams. I’d tag along with the teams. Sometimes there were cracked heads due to not enough material around the combustion chamber, so I made sure the new head [for EFI] had plenty of material around the combustion chamber.

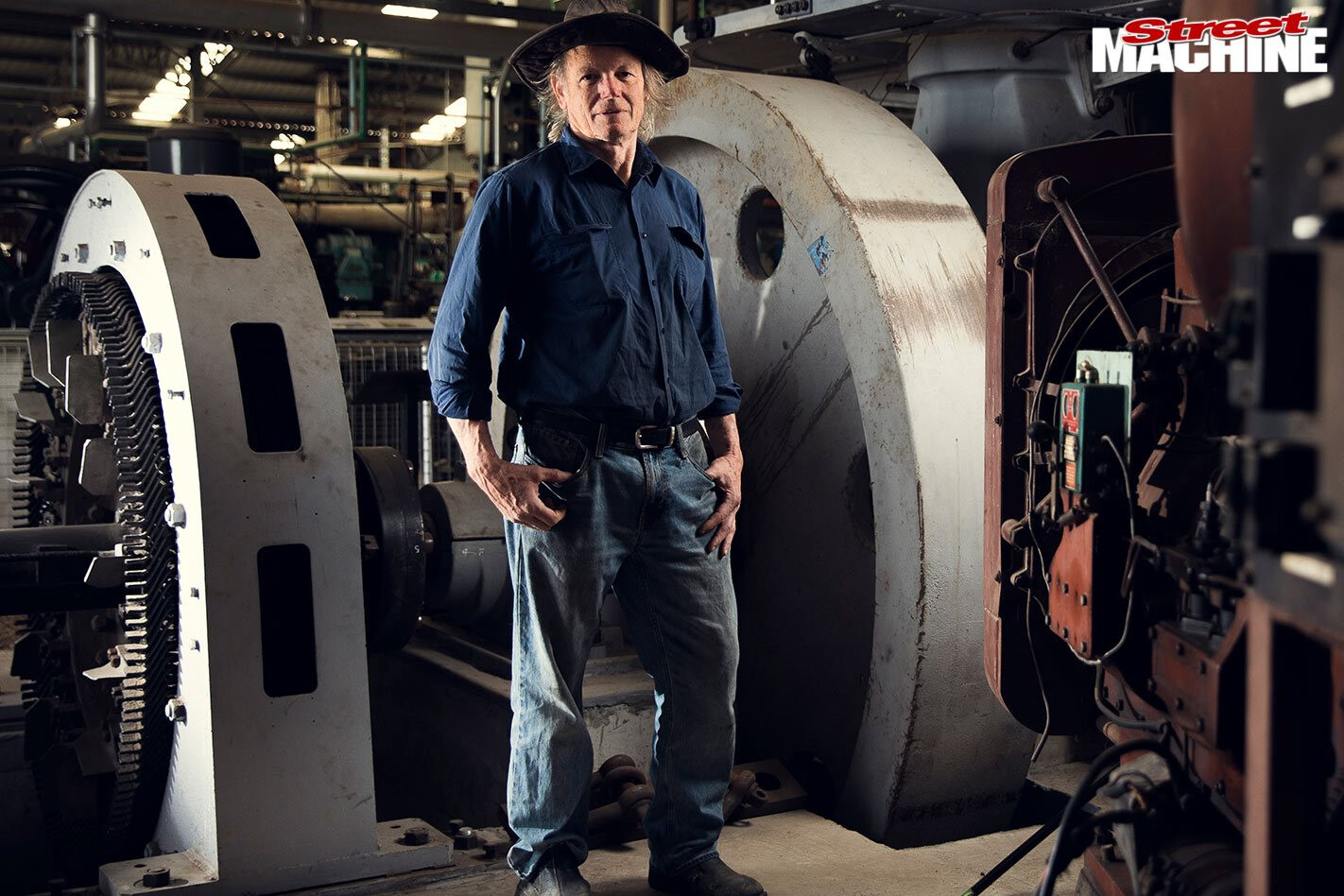

This is a five-cylinder, 200hp National diesel-powered 1947 Ransomes & Rapier walking dragline. Manufactured in England, it was imported as a kit and used for open-cut coal mining in Gippsland. “I was involved in restoring that,” says Warwick, “and now I get to drive it!” It’s one of the toys he plays with at the National Steam Centre in Scoresby

So you made the EFI heads tougher?

Yes – it was far more than you’d need for a road engine. While I was there, I made sure the ports were big enough for 500hp, which meant they were a wee bit bigger than what you would normally have in a road engine. So all these enablers were in there – things that enabled it to make more power to be used for racing [laughs].

This is awesome!

The V8s had conrod breaking problems, too. Mike Webb sorted out the conrods so they became just about indestructible. I’m not taking credit for that, but it was another enabler that snuck in! We did a fair bit of work on the lubrication systems, too. We put in windage trays and oil separators and that type of stuff. We’d had a few instances of V8 bearing failures pre-VN, especially in police cars swerving and braking. The race blokes didn’t suffer this because it was anticipated and they had appropriate sumps. So we added a bit of that race tech into the VN V8.

Speaking of police cars, were those rumours about ‘cop chips’ true?

There was actually nothing done to the engine calibration [for police cars]. The electronic control module had more shielding around it so it didn’t affect the radio, and there was other stuff that Holden fitted, like a more accurate speedo. Some of the older carby manual cars had big-valve heads, but there was nothing special about the engines for the police once the fuel injection went on.

That VN V8 is a very durable and well-respected engine.

The VN series got delayed. The prototypes had Nissans, but they went to the V6 [the US-designed Buick 3.8-litre] just a year before launch, so that put a huge extra workload on VN development. So we put the V8 on hold. But that meant we’d have to be racing VL V8s after the VN was in production because we didn’t yet have the V8. We needed to have sold 5000 fuel-injected VN V8s to be allowed to race it, as it was a new chassis. We decided we’d put the VN-type fuel injection onto the VL – the VL Group A – as we’d only have to build 500 of those to race with the fuel injection. So the VL Group A with EFI was a stopgap to keep it competitive.

Congratulations for getting that through!

Most of the company didn’t know it was happening. And some people – to their great credit – knew it was happening and could have stopped it but didn’t! We had a couple of test cars that didn’t really exist – a silver VK SS and a normal VL. I remember we were working on one in the experimental garage and a chief engineer walks in and says, “Oh, is that the new fuel-injected Group A?” And I say, “Yeah, I’ll have it going in a couple of weeks.” And he says, “Oh, that’s amazing – you’ve done so much in three weeks since the program was approved!” But we’d been working on it for six months!

So despite it being an older car, the VL Group A was developed after the VN V8?

Pretty much, yeah. The VN V8 program pre-dated the VL Group A, but the road-car VN V8 was delayed for the need to concentrate on the V6. People know it as the Walkinshaw, but it was a Holden Motorsport car. Holden Special Vehicles was only contracted to build the cars.

How about the VN SS Group A?

That was a lot easier. It was legitimate right from the start. It was an official program with company backing right up to the managing director of sales and marketing. We had proper resources and we had everyone on board. We went around to everyone that was racing a V8 Commodore and asked: “What do you want for racing?” We got a wish list from everyone, such as putting more meat in the ports and stronger conrods. The block was reinforced and had longer head bolts and four-bolt mains. There was a whole lot of improvement and heavy-duty parts. A lot of them stayed in the castings in the normal motors.

That 5.7 stroker was okay, too.

I’ve got to give Ron Harrop [Harrop Engineering] the credit. He built a couple of engines for us; we got interested. We productionised it, but it evolved from Harrop’s version that [at first] used Chev cranks and pistons. We always worked in conjunction with HSV, but it was HEC [Holden’s Engine Company] that developed and sold the engines to HSV. In my opinion that was a magnificent engine.

The Holden V8 lasted almost another 15 years – that’s a good run.

For VT, the imported all-alloy LS1 V8 was waiting in the wings. That was a long program to get into the car – there was a huge difference in the wiring and the engine control system and the emissions. Because [VT Series I] was the last of the Holden V8s, it was: “Don’t spend anything!”

Then six months later it was: “Do something!” So we got stuck into it: sequential fuel injection with a mass flow meter on it; we changed the heads a little; we had narrow rings and roller followers for less friction. Better fuel consumption and more power with better response; that gives you wins. So it was a happy combination. Even in the heavier VT, the V8 got better fuel consumption because our gains offset the bigger and heavier car.

And into the noughties?

Before I retired in 2008, I went over to Opel in Germany for a couple of years. When I got back, we did a diesel Commodore with an in-line six-cylinder BMW. It never went ahead – obviously – but it was a good jigger! All the commercial side of it was worked out; it was done with BMW’s co-operation. We fiddled with some hybrids, too. We looked at orbital technology, the Sarich invention, for the HF Alloytec V6 aimed for VE. We had Melbourne Uni involved.

What was the worst car you worked on?

The Camira! There were some dreadful quality problems. That 2.0-litre JE series was a good car at the end of its run, but it had a bad name by that time.

What are you up to these days?

I mainly indulge in my hobbies – old heavy machinery!

No cars?

Not really. If I had unlimited resources, maybe I’d have a couple, but it’s not top of my list. I like big diesels – trucks and earth-moving stuff. I’m mixed up with a steam engine mob, too.

Comments