Fifty years ago, drag racing was one of those activities that seemed like a good idea to just a handful of people in Australia. Among the youthful faces were a few more mature participants who found a home in this new activity and brought instant credibility to the sport. One of those was a Melbourne engineer by the name of John English.

First published in Street Machine’s Hot Rod magazine 10, March 2013

Today his face beams as he recalls the days when this new motorsport was sustained by just a single strip — at Riverside in Melbourne — and you fashioned your own racing destiny with a blend of daring and the contents of your garage. His memory is good, his wits sharp and his legacy still charges down the quarter and eighth-miles that now dot the Australian landscape.

Despite the wheelchair, John is a sprightly 88, going on 19. He had no motorsport background before he discovered the quarter-mile. As an aircraft fitter and turner before WWII he was just a young working class guy making his way in the world. However, he still had a touch of the lair in him, and modified the flathead in his ’47 Mercury to “hoon it up on the street”.

That brought him into contact with the Southern Hot Rod Club, the first in the nation, which he joined in 1958. He gave the old Merc a few squirts on the largely dirt Pakenham quarter-mile outside Melbourne, before it shut down.

John sold his half-share in an engineering business in 1960 and went to work for GMH and then Repco Research as workshop foreman from 1961.

In the early 60s Repco was a very different beast to the retail outlet we see today, its commercial interests extending from anything automotive, such as developing Formula 1 engines for Jack Brabham, to engineering world-standard wool spinning machines.

The first Saturday of each month was declared ‘foreigner’s day’, when the staff had access to all the workshop facilities to build whatever took their fancy. John decided he’d finish off a partly built rear-engined hillclimb car he’d bought, using the hot 239-cuber he’d saved when he’d sold the Merc a few years earlier.

The rear-engined concoction featured a torsion-bar front and early Ford independent rear. John took it out to the new Riverside dragstrip in June ’63, and then continued the quarter-mile activity, with at least one Top Eliminator trophy, until the August when he decided to give the annual CAMS sprints at Geelong a shot.

Lacking a CAMS licence, he handed the driving duties on to fellow hot rodder Greg Goddard. On his first run in the car, the back come around on Goddard and he went through the hay bales near the finish and collided heavily with a power pole on the closed road track. The engine tore out and bounced down the road. The car was destroyed.

As John wanted to keep pursuing points in the Robert Bosch Trophy series being run at Riverside he hurriedly did a deal with speed shop owner Eddie Thomas to drop the repaired sidey into the dragster chassis which Thomas had recently acquired from Goddard. Like we said, it was a small sport back then.

“I‘d known Eddie since we’d both worked at the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation,” John says. “I’d been doing some machining work for him so we had a lot of background.

“Eddie didn’t want to drive the car and I was pretty much fearless at the time.”

So in September 1963 John scored low ET (13.11) and top speed (123mph), working down to a 12.02 pass in December, setting a new strip record.

The following January, Adelaide’s Alf Mullins and Ian Bell brought their blown Chrysler dragster over for its first appearance at Riverside and despite blowing a clutch, it pushed Thomas to build a 318 Chrysler wedge motor for the dragster, with a front-mounted Marshall blower. In March ’64 the car finally fired a shot in anger and English’s racing moved into another dimension.

You must understand that these were the days when virtually every car on the quarter ran old road tyres — the primo ones being from Rolls Royces, as they tended to be removed before they were completely buggered and were as wide as were manufactured at the time. In those conditions, high 12-second times were fast enough to win you a Top Eliminator trophy with your Holden or sidevalve-powered car.

When a blown V8 — even the lower pressure set-ups of the day, with compression ratios not far off standard and maybe aviation fuel pumped through caburettors if you were lucky — cracked into life through open exhausts, a new era was born.

This had occurred at some sprint meetings in NSW as early as 1959, but now on a dedicated dragstrip and under hot rodder control it opened a pathway for the Top Fuellers and Funny Cars to come, for Wild Bunchers and Supercharged Outlaws, for Top Doorslammers and anything that needed bulk grunt on tap in an instant.

The combo was new, and so English’s estimated 400 horsepower stumbled off the line before clearing its throat and cracking on at its first outing. The short dragster frame, built to run a carburetted sidevalve motor on a dirt quarter, rocketed away to a near 135mph top end. The time or speed were never recorded because suddenly there were other things to consider.

The Riverside strip was roomy, with more than half a mile of braking area available. Or it had been until that weekend.

The GMH engine plant next door had decided to expand operations and simply annexed half of the braking area, pushing a mound of dirt across the asphalt to stake its claim to the rest.

“I landed in the water up to my waist and the car began to sink. I thought I was a gonner”

As English crossed the finish, going a lot faster than he ever had before, he grabbed for the brakes — nobody ran a parachute — and realised he’d overdone the 1934 Ford drum brakes.

“As hard as I worked on the brake lever, I just couldn’t get the thing to slow,” John recalls of that heart-stopping moment. “I thought it was the end of the world.”

In an attempt to skirt around the end of the earth berm in a wide sweep, he clipped it, became airborne and finished up more than waist deep in water in the adjoining swamp.

“I landed in water up to my waist and as the car began to sink further, it rose towards my chest. I thought I was a gonner until it stopped at that level,” he recalls.

Rescuers arrived and wet but unharmed he walked away.

Thomas took the engine home, cleaned out the water and mud and had the Chrysler even more on song for the following month’s meeting, when English was to be matched alongside the Mullins and Bell dragster; the first head-to-head clash of blown dragsters in the country.

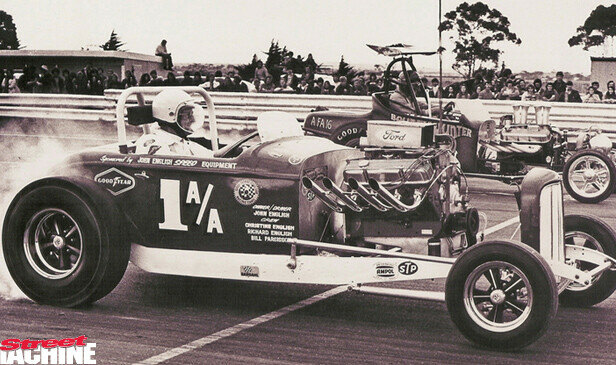

The moment is frozen in a yellowing photo taken on the day. Alf Mullins sits casually in the cockpit of the South Australian dragster, helmet on, strapped in, ready to go. English slips into the seat of the Thomas dragster as his crew stands by. In the near background a group of expectant fans watch, the girls in three-quarter slacks and beehive hairdos, the guys in stovepipe jeans and desert boots. The pressure is captured.

Minutes later the two faced the starting lights. Again the moment was captured. Mullins gets the jump, a girl flinches away, guys crane forward for a better look. Mullins hauled away to a win with 11.88@130mph while 39-year-old English trailed across the line after the motor again refused to clear its throat.

Frustrated, the team fitted a set of tyres borrowed off a ’48 Merc in the pits, replacing the slicks that they thought were bogging down the motor. With a reduction in grip the dragster spun the street tyres off the line and performed the first full quarter-mile smoky seen in Australia, ripping a few thousand miles of wear off the rubber on the way to an [email protected] pass and a new record.

Later in the afternoon they reinstalled the slicks, gave it more revs off the line and howled to 11.05 at another 140.6mph for a national quarter-mile record.

That was John’s last pass in the dragster. He had asked Thomas to fit a new seatbelt while he installed a set of discs to replace the tired drums but when the former wasn’t in place and with performances leapfrogging, he figured he would press on with the ’32 roadster he’d been assembling at home.

“I wanted to be top dog, and worked pretty hard at achieving what I did. It was a lovely experience to be who I was and what I did,” John says today.

He is still regarded as one of the sport’s true gentlemen. His best memories are: “The people I met, the reception I got wherever I went. I’m really just a nice old gent living in a retirement home and it amazes me that people still remember me for that racing 50 years ago.”

His son, Richard, proudly displays a picture of American dragster racer Tony Nancy’s rear-engined dragster, which ran here in the Dragfest tour in 1966. Written across the front is: “To John, a dedicated racer.”

That’s as good a summary as you could ask.

The Roadster

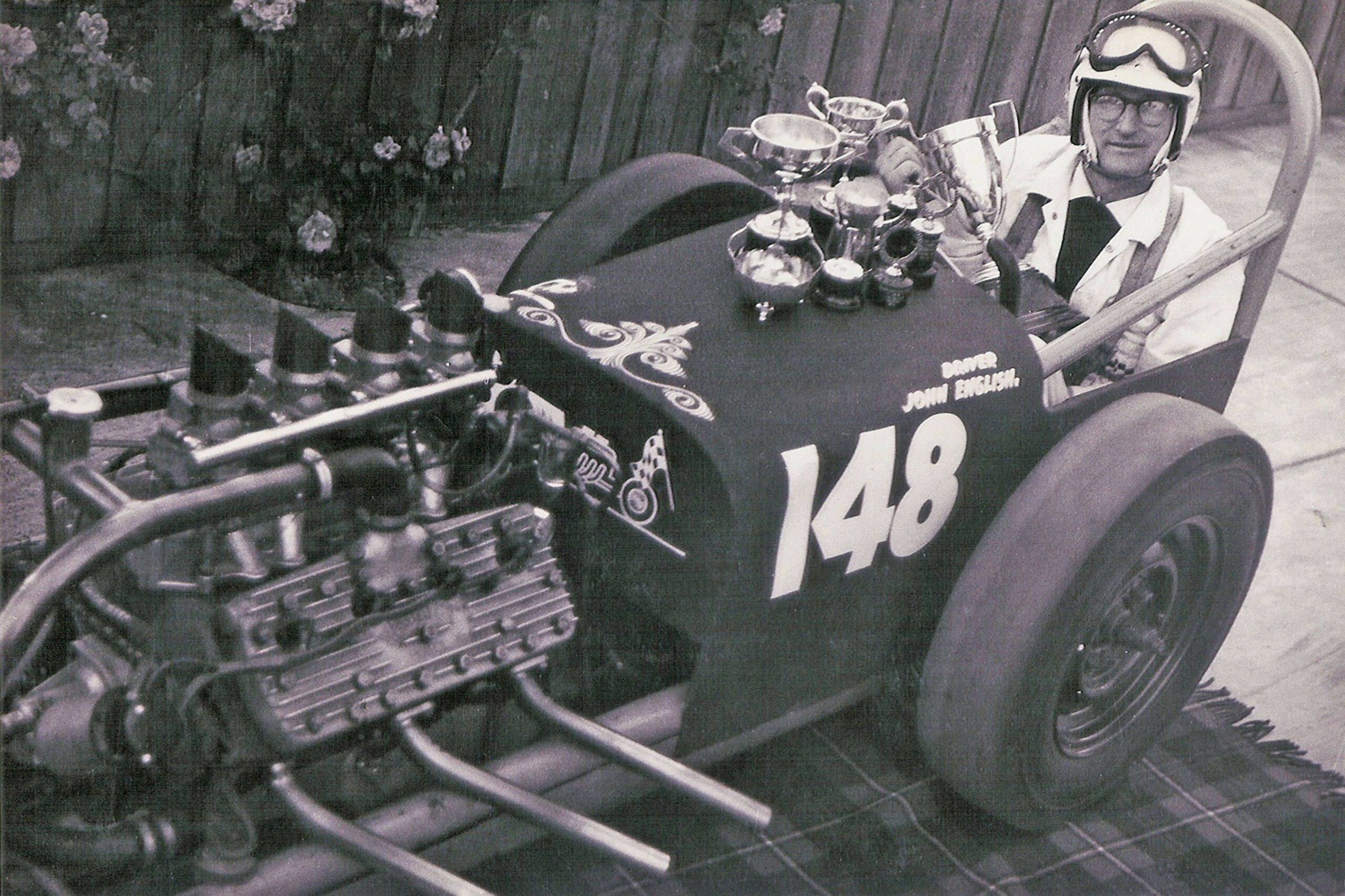

One of the most famous of all Australian hot rods, John’s roadster was bought for £50 in 1954.

The gutted steel body sat on the ’32 frame, with a ’47 Mercury engine mounted with the crank the maximum allowable 24in off the ground, and way behind its original location. The finished car cost £250, plus the engine.

The engine made 160bhp via four twin-choke Holleys, a Weiand manifold, Waggot heads and Vertex maggie.

Debuted in September ’64, the roadster scored enough extra points in that year’s Bosch Points to earn number 1 for the car and the £150 prize money. That was the last year of the Bosch series, so there was nobody to take the number off him, and when the Australian Hot Rod Federation was formed, national director Trevor Edmonds formally handed it to John in perpetuity.

It ran the first meetings at Castlereagh, Brooksfield (Adelaide), Surfers Paradise, Calder and Adelaide, and to bests of 12.73@109mph with the sidevalve upgraded to 296 cubes courtesy of a CT Automotive stroker kit — purchased for £295 when John was earning £45 a week — and a rebore to 33/8in, lifting the power to 210hp at 6000rpm.

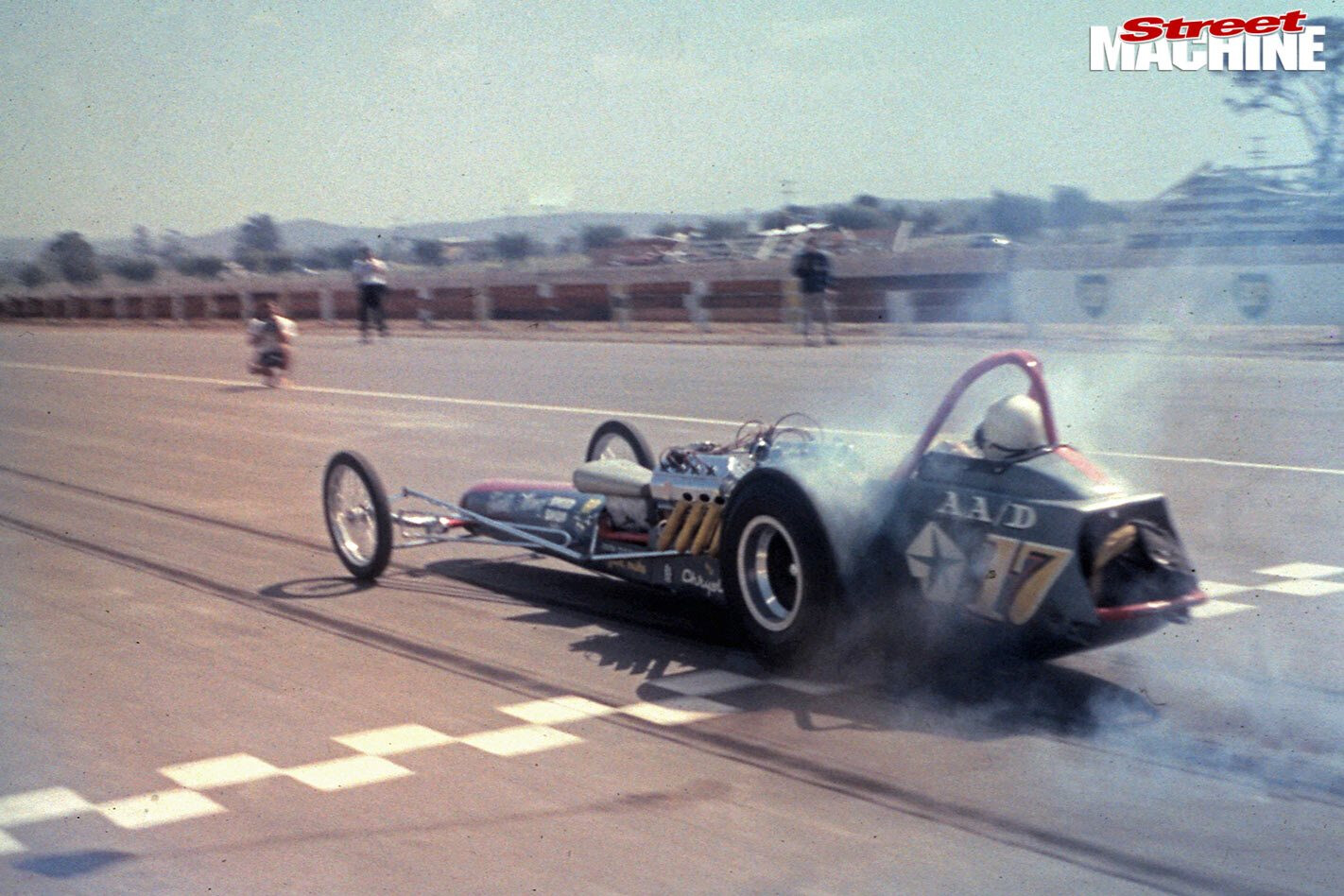

The sidey was replaced by a 390 Galaxie motor in 1970. Fitted with triple two-barrel carbs, the roadster went to 11.12sec and 130mph, but by late 1971 John had simply run out of money and with the competition pushing altered performances into the nines, the all-metal hot rod was seriously outgunned.

In January 1972 John towed to the opening race at the new Adelaide strip. “The car had a shortened sidevalve Ford gearbox with only two speeds, and it tore it to bits. It was the last time the car ran,” John recalls.

Comments