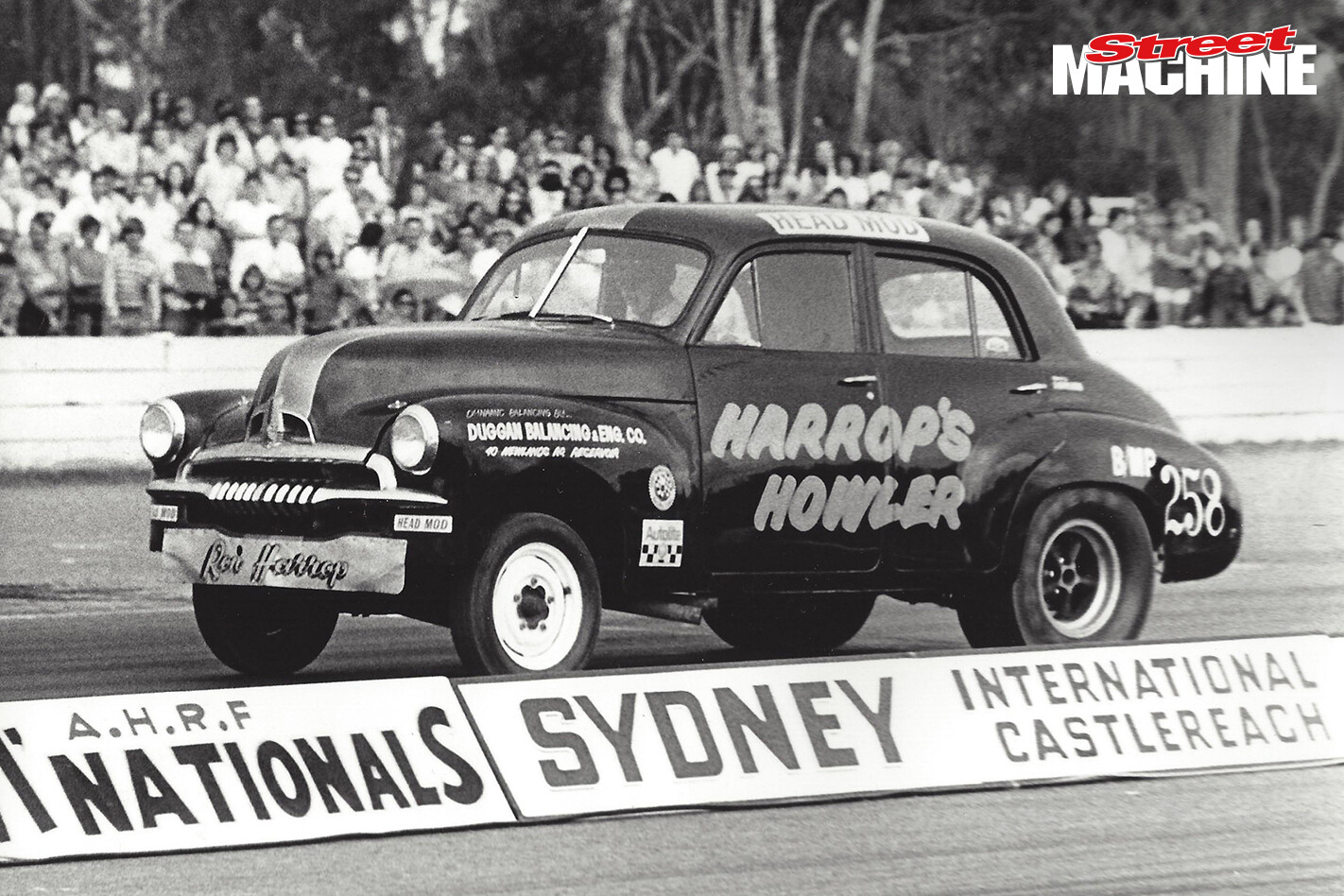

RON HARROP has appeared in the Legends section of the mag before (SM, Mar ’00). On that occasion we discussed his time as a driver for HDT, his role as chief engineer at HRT in the early 90s, and his massively successful Harrop Engineering firm. But what about the car that kicked off his career: Harrop’s Howler?

Let’s start by taking you back to November 28, 1971. The place: the old Castlereagh drag strip in Sydney. The event: the Australian National Drag Racing Championships. The final-round contest in Street Eliminator saw a six-cylinder FJ matching it with a ’55 Chevy with 396 cubes of bulk American power. Surely this had to be a giveaway win to the V8? But it wasn’t.

Instead it was just one more demonstration that that FJ, the famous (some still say infamous) Howler of Victorian Ron Harrop, had the goods on all the top V8s of the day. Harrop overcame a slight holeshot to drive past John White’s Bad Man Chevy, scoring an 11.96sec win over the Queenslander’s spluttering 12.26.

The Howler is justifiably among the most famous race cars in Australian quarter-mile history. Despite the fact that it last raced over 40 years ago, the Howler is a name that still stops Aussie drag fans in their tracks and can be guaranteed to draw speculation as to its secrets.

How did – how could – a carburetted six-cylinder FJ run times as quick as 11.81 back in 1971? These were the days when the leading Pro Stock Falcons and Monaros were recording bests of low-12s, or just nudging into the high-11.9s. Surely there had to be some demon tricks: hydrazine in the fuel; nitromethane in the windscreen washers squirting into the carbie intakes; nitrous injection hidden inside the radiator hoses; bulk illegal extra cubes from some massive internal block rebuild. Something – anything.

So why not ask the man himself?

“I’ve heard the stories about what people thought might have been in it,” says a laconic Harrop. “But not too many want to ring up and find out the facts. It wasn’t that trick; it was just: thrash it to death.”

Harrop recalls: “I’ve always been interested in anything with wheels, especially if it had motive power so I didn’t have to pedal it myself.

“I bought an EH around the end of 1965, when it was about 11 months old. It was just intended as a road car. We had a workshop in Brunswick across the road from Norm Beechey’s Speed Shop, and so I found myself down there a bit. I got to know Jack Collins, Greg Goddard and Fritz Norton pretty well, buying camshafts, carburettors and manifolds for the EH. It went all right for its day, I suppose.

“Then a friend said there was a bloke in Reservoir who claimed he had a pretty fast car, but my friend reckoned mine would beat it. Anyway, a race was organised up in the back-blocks of Coburg and I won that. It all started from there.

“The drags began at Calder and I went out there. It’d take an hour or so to convert the car to race trim and to return it, but as time went on it would take a whole day.

“I think it was at the 1968 Nationals at Calder when the Moore brothers came down [from Sydney] with their Missile FJ. My EH was doing about 14-dead or thereabouts, and they were doing 13.7s and that dropped my jaw. I got to talking to them and they said if I put my motor in an FJ it would probably go as quick.”

Harrop bought a traded FJ from Beechey for $29, installed the engine, gearbox and diff from the EH, all in the standard positions, and $1300 later it ran a 13.42 at its first meeting (April 1969). So the evolution of the Howler began.

By July 1969 Harrop was second in the 12sec six-cylinder Holden ranks, behind NSW’s Brian Keegan. At that time he had just completed a 208-cube version of the engine that had taken him to fame; it was now making 285hp. The 179 crank had the big ends welded up and the counterweights carved off, replaced by Harrop’s own.

“It was just what looked right to me,” Harrop says now. “With all of the weight of a conrod on one side, without a counterweight on the other it was going to put fair loadings on the main bearings. We just welded them on and cut them off until we were happy.

“It had various heads, but they were all iron 149 heads, shaved 0.13in and ported and polished by John Bennett from HeadMod. Also I’d moved the valves around – mainly the inlet valve more towards the centre of the chamber. I think it ended up with a two-inch inlet, which is pretty amazing when you compare it with a standard head, where the valves are way over the sparkplug side. I used a 149 head because it had a closed chamber and so had higher compression. It finished with a dish in the piston and still had 13.3:1 compression.”

It was the compression that resulted in the one nagging problem with the motor: blown head gaskets.

“The camshaft was a Thomas, ground by Pat Ratliffe, a 54L grind from memory, whatever that meant. It was based on a Chev Duntov grind that had a bit ground off the nose. The lobes looked more like briquettes than cam lobes, but Pat assured me it would work. At the end we had 343hp at 7800rpm.

“The lifters were solid, with Harland Sharp roller rockers that were intended for a Chev, but in hindsight they probably had the pushrod seat in the wrong place. We didn’t know those things in those days. We bolted them on and they pushed the valves open so that was fine.

“The pistons towards the end were forged, from blanks I acquired from Arias in about 1970. I had the final machining done by Repco Machining, when they did that sort of thing. The conrods were massaged standard-Holden. I broke one or two, but essentially they were good.

“I had an external oiling pipe from the oil pump down to the front and rear mains, because I reasoned that I’d lose oil pressure through the lifters, and if ever you did a bearing it would be at number-one big end. I note that pretty well everyone does that today.

“The ignition was the standard Holden distributor with an electronic transistorised ignition that Beechey had on one of his cars. In back-to-back testing it gave 7hp more than the Lucas or Bosch coils that we had used previously.

“Initially I started with SUs but I finished with Webers. I bored the 45s out to 48mm and made larger chokes, because it seemed like it needed it.

“The fuel delivery was a pair of Stewart Warner electric pumps. I ran it on 115 octane fuel.

“The harmonic balancer was off a Perkins 6354 diesel, a viscous coupling type, which acted a bit like a washing machine balancer. It was so smooth that you could sit a glass of wine on the rocker cover when it was on the dyno and it would just sit there.”

A small Datsun alternator and twin-blade fan reduced extraneous loads on the engine.

“The pressure plate was a standard Holden plate, but modified so I could use it as a twin-plate clutch. It had an extremely heavy flywheel, about 1¼in thick and weighing about 30lb. That helped to launch the car because it had fairly large Goodyear slicks in the end without a lot of power.

“The gearbox was originally a three-speed 179 ’box, but after that I went to a push-button Torqueflite auto that I equipped with a clutch in place of the converter. In the end it had a Toploader close-ratio ’box.

“The rear end was a 10-bolt Chev, like the old ’55-’64 diff, with a 6.17 ratio. I was launching it at around 7000rpm and revving it to about 8400rpm at the finish when it was running the 11.8s. It would get to maximum revs about 100-200ft before the finish.”

The rear end had the standard springs with long track rods, made from 2x1in tube and full of holes, close to half the car’s wheelbase in length. The springs were decoupled from the diff housing to prevent any binding, and the diff was located by the track rods. At the front were the standard 90/10 shocks.

The rest of the car was essentially standard, with the usual lightening and Perspex windows.

“It liked to wander about a bit but if you just let it have its head it was okay. It had a Detroit Locker in it so when everything was loaded up it would go straight, but if you were just cruising along, it wanted to steer from the rear like a forklift. A hundred miles per hour in a forklift can be a bit dangerous.”

Running a car like the Howler meant always trying new ideas. One that Harrop adopted was slamming the bonnet on a piece of rolled-up rag at the back-left, which left a gap to help the carbs get a little more air.

“At the time it was just what you were doing and it didn’t seem that big a deal,” Ron says of his time running the Howler. “But today, judging by the number of people who want to talk about it, I look at it in a slightly different light and it’s all quite flattering.”

Comments