This article on Bill’s EA Falcon was originally published in the June 1991 issue of Street Machine magazine

NOW BILL Jones can take it easy. It’s all over. But most days he couldn’t, the customers kept getting in the way. You see, they all wanted stuff such as nine-inch cut-and-shut Ford axles. Or rear disc conversions. Or full-race chassis or mega-wide fabricated wheels. Great. But it kept dragging Bill and the boys at Weldwell away from the really important issue. And, of course, that was building the ultimate Pro-Streeter: the Motorcraft EA Falcon. They had wanted their EA to star in Summernats 4 – that was, until the flood of work from bread-and-butter customers just ran them right out of time.

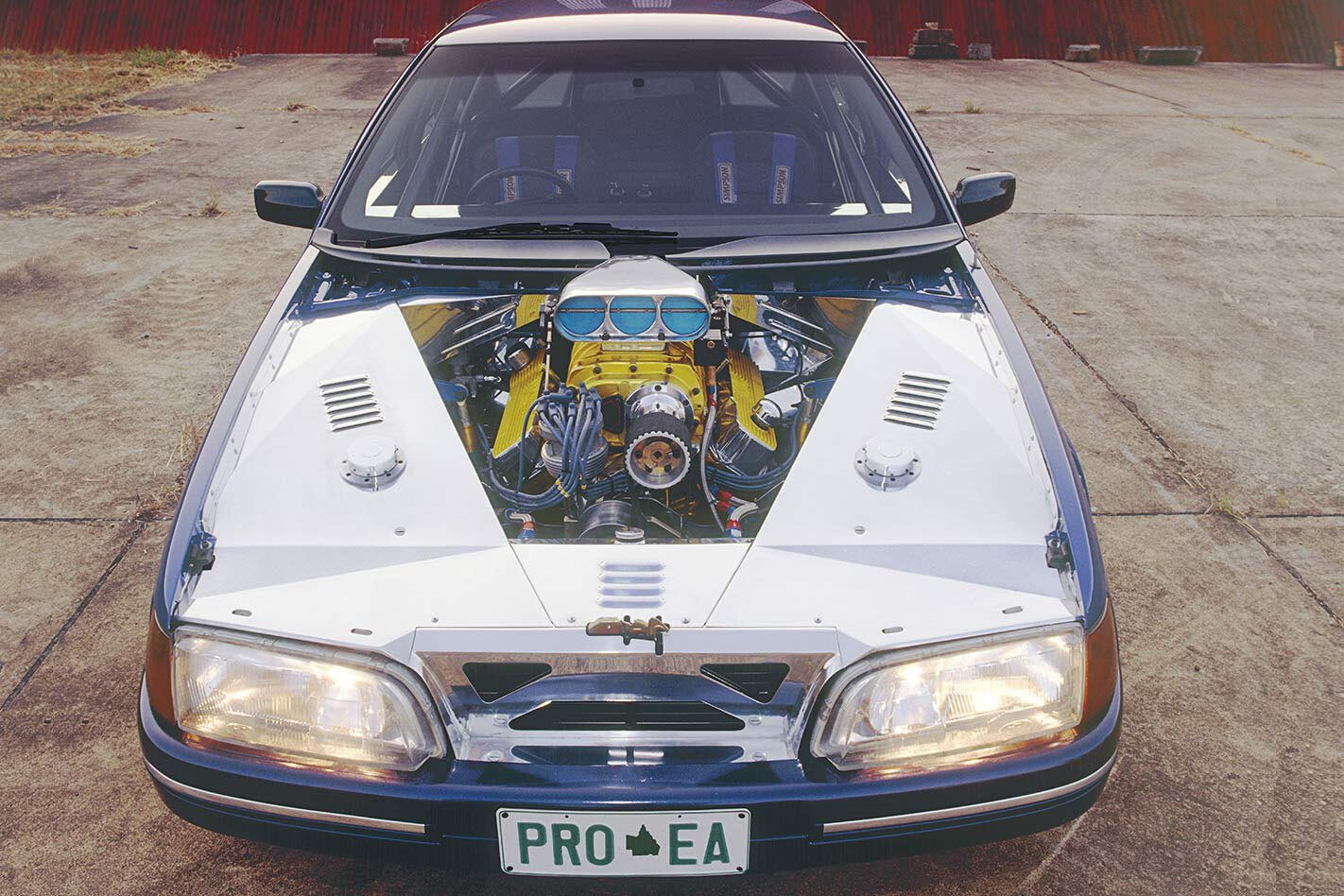

Almost 18 months from the day they off-loaded a brand new EA Ford Fairmont Ghia bodyshell in the backyard, the Jones-built Motorcraft Pro-Streeter was up and running. Right down to the tinted electric windows, the Clarion stereo system, the digital clock in the dash… Then there’s the full-tube chassis, the 8/71 GM blown 351, the fat tubs that hide humungous 33×21.5/15 Mickey Ts.

The concept’s sensational; the engineering awesome; and the final product’s a showstopper. To date, it’s the best mutha to roll out of Weldwell’s gates. Just think, this beauty was the result of a rap session between Bill and Street Machine.

Both parties reckoned Holden had the show scene by the short and curlies. There had to be a real opening for Ford – especially a Pro-Streeter based on a current model shell. That’s if it were built right. Bill had the talent; Street Machine had the connections…

A plan was forming. Then there were talks with John Beveridge, Ford’s advertising and sales production manager. Simple. Ford would supply the EA shell, along with genuine parts to fit out the rolling chassis. The rest was up to the Weldwell team.

Lift the lid and check out that fabricated sheeting around the blown 351

There was no question that the car was going to feature a full-tube steel chassis. Although as a true Pro-Streeter, the mainly 10-gauge, 15/8in TIG-welded multi-tube assembly wouldn’t be running racecar-style cross bracing. So the chassis is there to carry loads from the engine, drivetrain and suspension – along with that all-important job of totally supporting the now savagely gutted EA bodyshell. And, opting to be really radical, Bill sat up nights and plotted out a super-trick suspension set-up.

His car had to be low. So low it would sit just two inches off the tar. This instantly created problems with ripple strips and lumpy level crossings. The radical new suspension would be based on Weldwell’s own already proven components. Like the fabricated front struts, which combined stubs and steering arms with coil-over shock units, and the coils sitting on height-adjustable spring platforms. Linking the lower ends of these struts to the chassis is a pair of tube-steel A-arms, and at the top end, the struts connect directly to the chassis-pivoted bell cranks.

How low can you go? Try two inches from the ground thanks to trick adjustable suspension

This is where the tricky bit comes in. The cranks are there to transfer the push from a pair of rams, one on each corner, run on hydraulic pressure generated by a liftgate pump from a truck, and already neatly combined with a 12V electric motor and oil-storage tank. Flick a switch and the pump whirrs into action, those rams push on the bell cranks and the car lifts another 90mm! The same system aids the rear suspension. The narrowed-to-buggery nine-inch Ford axle, located by four links and a reversed upper A-frame that pivots off the top of the diff, supports the chassis via a pair of coil-over shock units. Same upper bell cranks, same hydraulic rams, same result. Bill wanted things to look right, so an in-line restrictor valve ensures when the car lifts, the bum goes first.

Weldwell was originally going to fit a Watts linkage to tie down the fully floating hubbed rear axle – along with onboard jacks that also tapped into the already installed car-lift system. The jacks will come later, but the Watts link had to be axed when the team discovered that the full, through-to-the-tail exhaust just didn’t leave enough room.

Without really wanting to, they made some extra space when they were first test-running the engine. You see, as a part of the dual exhaust system, Bill and the boys made up this massive box of a muffler. All of this was hooked up to the blown 351 Windsor when they began to crank the eight into action. It didn’t want to fire and, despite careful precautions, the muffler filled with raw methanol. When it went bang, so did the muffler!

Logan Specialised Services did most of the machine work on the two-bolt main bearing, 30-thou-overbored 351 Windsor block. It runs a stock crank, while Ford rods hold up a set of TRW flat-tops. These are set up to match with 2V heads with enlarged combustion chambers, which drop compression so that the engine will live with a 25 percent overdrive 8/71 GM huffer. This is driven through a toothed belt that runs around a combo of Weldwell-made action and idler pulleys.

One of the trickier bits here is a fabricated crank nose-support mount built into the chassis. This mutha takes the blower-drive load off the overstressed crank nose. Bug catcher-mounted Enderle injection draws fuel from another typically Jones-created engineering solution. As the blown and injected 351 is sure going to use a heap of methanol base fuel, double rear pumps were installed to push the stuff forward from the twin rear tanks. Although when the peak demand hit was open there was a good chance the twin pumps would miss out keeping up with the hard-charging injector pump. Bill’s solution? A front-mounted fuel reservoir. Of course, he built his own – adding a needle valve and float from a Holley carb to limit the special tank from overflowing.

Fabrication work inside the EA is mind-blowing

The boys couldn’t buy the right blower manifold for the 351 Windsor, so Wayne Jones sat down and made one. It’s a low-profile special that keeps the bug catcher down to a respectable height. And as the blower drive got in the way of the stock front-mounted dizzy, the team also custom-made an offset-drive spark machine that slots into the stock block hole, using a machined alloy housing-enclosed tooth belt drive to take the distributor body out clear of the blower nose. As they didn’t like the usual Autolite dizzy body, they made up their own polished aluminium piece. This is topped off with a Ford Motorsport import cap.

As you might have guessed, Weldwell isn’t heavy on importing American bits. But they did freight in the cam, lifters, chrome-moly pushrods and a full set of valve springs. All Doug Herbert stuff, the cam lifts 0.720in and runs a total duration of 351 degrees. Crane roller rockers push on Manley stainless valves in home-ported heads, the inlets with 2.080in heads and the exhausts 1.880in. Cooling this mean mutha is a little old alloy radiator from a VW Passat, a crossflow job fitted with thermo fans, which runs coolant back to a remote-mount header tank.

“We really did put a whole lot more into the engine than I really wanted to,” Bill explains. “When we first started it up, the donk was still sitting on the floor. It made this enormous noise and just about ran straight out through the door!”

Handling all this grunt is a C4 Ford auto. Spinning a TCI 3500 stall converter, the tranny is manual shift-kitted and cog-swapped through a set of Hurst Lightning rods. A severely shortened driveshaft runs back to the nine-inch, which wears a Detroit Locker, 4.88 gears and 31-spline Hi-Tuff axles. The jumbo mumbo then goes groundwards through the fully floating hubs to spin heavily reworked steel 12-slot Falcon wheels. These began life as 14x8s, later modified and widened to 15x15s, clad in Dunlop road tyres. This is just a hint of the clever engineering here.

Weldwell also machined up the steel rotors for the four-wheel brakes, the four-spot alloy calipers and the brake master-cylinder assemblies.

The disc rotors read out at 11-inch fronts and 12½-inch rears, acted on by those custom-made four-spot calipers fitted with pistons and pads that were once designed for superbikes. And the brake master cylinder? An in-house tandem design, using big-bore first stages to fill the four-spot calipers, then transferring the pedal pressure through a valve to smaller-bore cylinders. These step up the hydraulic ratio and finally perform the actual stopping chores.

Inside, the stock-profile Fairmont Ghia starts off with an instrument panel assembly from a Falcon S Pack. Set into a polished alloy dash, another alloy extension houses more instruments and runs down to the centre console. The door trims and the one-bum rear seat are polished alloy, while the front buckets are moulded from glass fibre. The Weldwell team designed the unique steering wheel, Simpson supplied the five-point seat harnesses, Advance Trimming looked after the carpet and vinyl. Outside, Darren Jones and Greg’s Body Works combined to massage the EA shell, and Southside Ford supplied the Spartan two-pack primer and paint. The colour ended up being called Spike Blue, Spike being the guy who mixed in those colour tinters!

It’s one hell of a Pro-Streeter. There’s one problem though. With only three seats, somebody’s going to have to sit on the roof…

WELDWELL ENGINEERING

1990 FORD EA FAIRMONT

Featured: June 1991

Cool info: Lots of home machining and fabricating in this mighty EA, from the blower manifold to the muffler – even the brake rotors

Paint: Spike Blue

Engine: 351 Windsor

Gearbox: Shift-kitted Ford C4

Diff: Narrowed nine-inch, 4.88 gears

Wheels: 12-slot Falcon

Ride height: A-arms moved by hydraulically adjusted bell cranks alter ride height, boosting ground by up to 90mm

Comments