Every time the covers are whipped off a new billet engine block design, car fans hit the limiter like a P-plater in Dad’s company car, frothing at the 3000+hp potential of these aftermarket platforms. But what are billet blocks actually designed for?

First published in the January 2022 issue of Street Machine

As high-end racers in drag racing, Time Attack and other forms of motorsport chase the seemingly opposing goals of reliability and ever-climbing power outputs, specially machined engine packages have become the hot new go-to. This is where the billet block comes into its own.

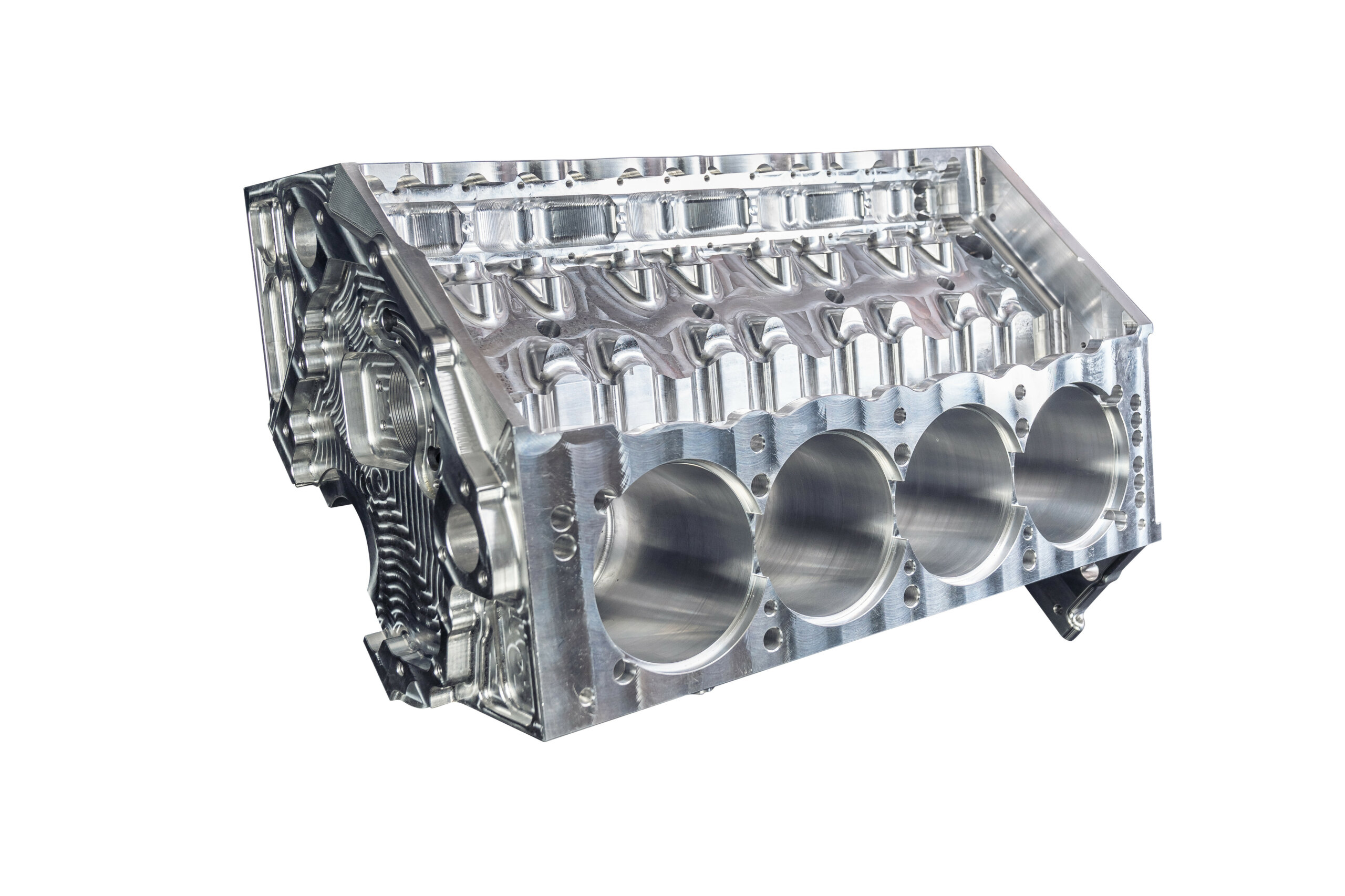

Traditional engine blocks are made through a casting process, where liquid-hot aluminium or iron is poured into a mould and allowed to cool. Perfect for mass-production runs! A billet block, however, is machined from a single solid piece of super-high-quality metal called a billet.

South Australia’s Bullet Race Engineering has recently added billet Holden V8 and Ford Barra six engines to its existing product line, which includes billet blocks and heads for Toyota 2JZ and Nissan RB six-pots, as well as Honda K-series, Mitsubishi 4G63 and Nissan SR four-cylinder donks. The team have poured huge effort into improving the engineering behind some of our favourite engine formats.

“The guys buying these engines are really going all-out with them as they push for maximum power or maximum reliability,” says Bullet’s Darren Palumbo. “You can make 1000hp on the stock versions of something like a 2JZ for a time, but the risk is so much higher when you are pushing an engine that was never designed to make that power. These blocks are built to make that power.”

There are two major benefits to aftermarket billet blocks, the first being the opportunity to redesign elements of much-loved engines, massively improving their potential. These include modifying the size of cam tunnels and lifter bores, adding material around fasteners, adding modern priority mains oiling galleries and more. The other major plus is the metallurgical properties of high-quality aluminium.

“A benefit of going to a billet block is that while 6061 aluminium has similar tensile strength to cast iron, the yield is 10 per cent,” Darren explains. “That means it can move 10 per cent of its length or thickness before it will crack, compared to cast iron, which has a yield of 1-1.5 per cent. And if cast iron cracks, then it is junk, while the aluminium can be welded.”

This isn’t any old aluminium he’s talking about, though. Bullet makes its engines from billets of forged 6061-T6 aluminium, which uses magnesium and silicon to make up the complex alloy before being heat-treated for maximum strength. It is the same grade of aluminium alloy used in the construction of aeroplanes and firearms, and in chassis for supercars like the Audi R8.

“The quality of the forged aluminium being used, and the way our blocks are designed to hold strength in the right areas, means you don’t have parts of the engine walking around as they try to deal with many times more power than they were ever designed to take,” Darren says.

Once they have been machined into shape, the aluminium blocks are further machined to accept drop-in cylinder sleeves, and these can often be specified to run as wet (with coolant around them) or dry (like grout-filled, methanol-burning drag engines that run without coolant).

Bullet isn’t the only one in the game, of course. PAC Performance in Sydney has been building billet rotaries for years, while international outfits offering billet engine options include Alan Johnson Performance Engineering, CN Blocks, Pro Line Racing, Steve Morris Engines, Moran Motorsports and Elmer Racing. Noonan Race Engineering even moved its operation from Queensland to Spartanburg, South Carolina due to the growing market for billet engines.

Noted tuner and engine builder Frank Marchese of Dandy Engines has had plenty of hands-on experience with billet mills.

“Reliability is key, as the material they make billet out of is much stronger than a cast block,” he says. “The weight isn’t that different over a cast block, but a twin-turbo cast-aluminium or iron Chevy will only take 50psi safely. With a billet block, you can go 100psi.”

Being able to include upgrades in order to make engine servicing easier in between racing rounds is an important advantage of billet for Frank, as there can be big money on the line.

“Take the ProCharged PLR Alan Johnson Hemi that runs in the white Firebird [Tech Torque, SM, Apr ’21] – we can change a set of rods at the race track and it isn’t a huge drama, thanks to the simplicity of pulling a sump off,” Frank explains. “This Hemi has an updated design so you don’t have to remove the intake manifold to change a cylinder head. In America we removed a head and changed a valve in the pits in 45 minutes, but if we had to remove the intake that would have been hours of work.”

With the pace of change in racing, having the ability to update designs or roll in upgrades for the next season’s engine are key benefits for serious racers needing a four-digit power fix.

“The cast stuff is a lot harder to change; you’d have to redesign it, then recast the block to make those design upgrades,” Frank says. “I actually do a lot of billet stuff now; I do a 2JZ making over 2000hp for a customer in Sydney.”

While they’re not an option for budget builds yet, the billet block revolution could spell a lengthy future for internal combustion engines. As second-hand stocks of 60-year-old engines dwindle in the future, it is nice to know there are other options available to keep our favourite engine designs alive.

KING OF THE JUNGLE

Bullet’s new lightweight, billet-aluminium Holden V8 packs some spicy engineering to allow for a claimed 3000hp rating. It is available with water jackets in wet open-deck or closed dry-deck, and can also be ordered as a solid, totally dry, drag-only block. Bullet will offer 8.875in or 9.1in deck heights, with bores ranging from 4.125in to 4.185in, meaning a 440ci Holden V8 is now a possibility.

“Our new engine isn’t just a Holden V8 we scanned and have reproduced,” Bullet’s Darren Palumbo explains. “Our design is a siamese bore with an externally machined water jacket, meaning there is more meat around the fasteners for a stronger platform. And I’d expect it to be half the weight of an aftermarket iron block.”

There are four-bolt mains taking half-inch caps, while the cam tunnel has been pushed up in the block and now sports a 60mm tunnel and Babbitt bearings. Bullet reckons that Tighe Cams can provide custom bumpsticks to suit this new core size.

A weakness of the Holden 5.0-litre going back to the very beginning is the oil system, and Bullet claims to have that licked, with the company’s block using priority oiling just like a NASCAR engine. It still uses standard Holden mounts, so a plate mount isn’t required, and the crank tunnel takes standard Holden bearings and comes machine-finished.

Other options extend to two sump-rail patterns for standard or stroker cranks, and lifter bore options from standard 904 up to Jesel cartridge-style, though the Bullet Holden V8 will require an external oil pump for either the wet- or dry-sump system you choose to run. The block can be ordered to run a distributor or front belt drive, with the choice of either an exposed belt-drive timing set-up or a Rollmaster raised-cam chain set.

For fasteners, the Bullet block rocks half-inch head studs and inner main studs, and 7/16in outer main studs. The rear main seal is a Chev item, and the bellhousing runs a Holden ‘turbo’ pattern.

Want one? You’ll need $15,000.

BIG FISH

“This is probably the most requested engine we’ve ever done,” says Bullet’s Darren Palumbo of the company’s mighty billet Barra block. “We started on the Barra before the Holden program, and there was a whole heap of work in the background.”

Machined from 6061 forged aluminium, the alloy Barra runs an OE tunnel, bellhousing, rear main seal and engine mounts, but can accept bores from 92mm up to 97mm for a 4.5L capacity. Bullet ties the caps in using its four-bolt cradle system featuring 7 /16in ARP studs, while ARP 1/2in studs keep the head clamped down.

“We had to make major design changes to suit what we wanted this block to do, because of the way the factory Barra block is designed,” Darren explains. “The stock main caps hang down like a V8, but we prefer to run our main caps integrated into a girdle for strength, like on Japanese six-cylinders.

“On the other hand, it was important for us to retain the stock cylinder head fastener positions, so customers can also run a head or intake manifold that they might already have invested a lot of time developing to work with their car.”

As with Bullet’s Holden V8, the oil pump must be externally mounted, but the oil pan can be wet or dry format, and the block comes with Bullet’s billet integrated sump. Weighing in at approxim ately 45kg, the billet Barra can be ordered wet or dry with cooling jackets for $16,000, or as a solid, drag-only block for $15,000.

“This is for people who are looking to make power and be reliable,” says Darren. “We’ve actually sold six so far, with two being bought by one customer. One will go in his drag car and one in his street car!”

1. Bullet machines its blocks to take a .904thou lifter like a Chrysler, and offers an optional .937 lifter bore, but the ultimate is a 1in Jesel bronze-bushed cartridge lifter (at left and second-left in photo). “The bronze body encapsulates the lifter and wheel in a keyway,” says Darren. “The concept behind running a larger cam core and bigger base circle is to gain lobe lift on the cam at a lower rocker ratio, because as rocker ratio increases, valvetrain stability decreases”

2. These are billets of 6061 aluminium, which will eventually become Bullet engine blocks, cylinder heads and other parts. Jigs are attached to the blocks so the metal can be held by the machining equipment, as the block needs to be rotated while it is being machined for oil galleries, crank and cam tunnels, mounts and the like.

3. CNC stands for ‘computer numerical control’, which refers to the automated control of machining tools including lathes, mills, drills and 3D printers.

The CNC machine is programmed to follow a computer-designed model drawn up in the SolidWorks CAD program and translated into SolidCAM computer-aided-machining (CAM) software. SolidCAM then speaks in code to the machine, which cuts the material in a series of passes.

4. Bullet uses a Haas VF-3SS three-axis milling machine (with a fourth-axis rotary) to cut the aluminium billets into shape.

Once that’s done, the block has the jigs removed so the ends of the block can be machined in another Haas VF-3SS that can accept taller jobs. Then it is sent to be honed for the cylinder sleeves.

5. The CNC machine will automatically switch cutting bits out to suit the next piece of machining the program calls for.

Cooling liquid is sprayed onto the cutting bit and work surface to prevent overheating, which would make the bit go blunt double-quick. Given the price of these bits, it is important to keep them in the best condition for as long as possible!

6. The blocks are honed to accept iron flange-top cylinder sleeves, arranged in siamese fitment for better strength. “Using a siamese bore in the block assists us with block strength,” says Darren. “But it also helps to keep the deck flat and prevent distortion in the main crank tunnel. Essentially, it makes the whole block more of a beam construction, so it is less likely to distort under rpm or boost pressures.”

7. Being able to engineer upgrades into the block design is a huge benefit for big-power combos, and a great example is the notch in this Toyota 2JZ block.

The clearancing required in a stock 2JZ block when fitting large alloy conrods cuts dangerously close to the factory oil galleries, so Bullet designed larger galleries to sit higher in the block, so there is no danger of a broken rod taking out the oil gallery.

8. Aftermarket iron blocks are strong, but they don’t have the ductile strength of aluminium. The improved block strength from better-quality metal is a huge factor in the attraction of billet engines, especially as power outputs have skyrocketed in recent years, with some Radial vs The World cars making over 5000hp at the hubs!

9. “The factory Holden blocks are getting harder to source and more expensive, and it is also getting more expensive to make them hang together at today’s power levels,” says Bullet’s Darren Palumbo (centre).

“We basically identified the weak points of the Holden platform and remedied them in design, as the only restrictions we faced were the bore spacing, crank tunnel sizing, head stud location and physical size”

10. Before slapping your hard-earned down on a fancy billet block, it is important to do some research on what cylinder heads and internals fit, and what level of machining is required before it can be assembled into an engine. Some blocks come ready for bearings, while others still need plenty of set-up work.

11. “We are probably anodising maybe 10 per cent of the engines we’re doing,” says Darren. “Most of the guys choosing the coloured blocks are street-car guys. We’ve done them red, pink, black, blue…”

12. Sharp-eyed Cleveland fans should be excited by the design on Darren’s computer, as Bullet plans to release a billet Clevo in 2022. “We have found strong interest in the Cleveland platform, so we’re excited to offer this option next year,” he says.

13. “Everything is washed by hand, because the caustic in the hot wash makes the aluminium go dull,” Darren explains. “We probably do 150 blocks a year, and a four-cylinder takes approximately 20 hours to do, while something like a Barra or Holden V8 would need 30 hours”

14. This 3500hp ProCharged brute is the 564ci AJPE TFX from the Marchese-Szabolics Pontiac Firebird radial car (SM, Apr ’21), which runs 3sec passes in the eighth-mile on methanol. This is the level of race car that billet engine blocks were originally designed for, though they are now appearing in high-end street cars as well.

15. Former V8 Supercar engine builder Jamie Noonan has made an international success of his Noonan Race Engineering business.

Now US-based, Noonan offers billet Hemi, LS, LT and even Porsche 911-based billet offerings. Local Noonan customers include radial racers Kyle Hopf, Jarrod Wood (above) and Wade Wagstaff.

Comments