DURING the 60s, Detroit built plenty of hot cars. But for all-out balls nothing rivalled the Plymouth Superbird/Dodge Daytona series of muscle cars. If you wanted mega racecar styling for the street, you looked here. The wildest of these cars were aimed at drag racing, NASCAR oval tracking, or Sports Car Club of America road racing.

Dubbed ‘The Ultimate Road Runner’ by Plymouth, the Superbird was built in a desperate attempt to regain the NASCAR crown from Ford’s Torino Talladega. After winning Le Mans, Trans Am, NHRA drag racing and NASCAR, Ford had been pumping big money into its racing programs and the competition was feeling the pinch.

Surprisingly, there are no common body components between the Superbird and the Daytona wing cars. At a glance – and even parked together – they may look like twins. But in reality, Dodge and Plymouth were tough competitors who had the advantage of the Hemi engine. The two body styles were developed separately less than a year apart. While the Superbird used a Road Runner body as its base, the Daytona used a Charger.

The ‘wing’ cars came about when Chrysler engineers found they had reached the peak of horsepower/reliability from the Hemi. They needed to get the Mopars moving through the air quicker without extra horsepower. Ford had the NASCAR competition crown by the short and curlies and Chrysler wanted it.

The engineers knew they couldn’t push the Hemi to deliver any more grunt without losing reliability. But they did know they could make the cars cut the air a lot cleaner. Clean air flow equals horsepower … but they had one problem The aerodynamics on the ’68 Charger were about as smooth as a tin-roofed brick dunny as it accelerated to 180mph.

Just ask Chrysler Racing Group engineer, Larry Rathgeb. Larry was trying to solve these problems on Buddy Baker’s Charger, which was having stability problems above 160mph. While at Daytona, he fitted experimental spoilers to the nose of the Charger and taped in a perspex rear sheet over the recessed rear window hoping to get the Charger to sit stiffer on the road.

This sort of worked, but team manager George Wallace stopped track testing and sent the engineering team back to Detroit to do better. Surprisingly, Plymouth didn’t attend this meeting, which marked the turning point in the Dodge NASCAR stakes.

John Pointer, a young Chrysler engineer, and Bob Marcell, head of Chrysler’s Aerodynamic Design, both submitted proposals based on the Charger 500 body. Both concepts looked like the work of one man. It didn’t take long to get the approval of Dodge general manager Bob McCurry.

Pointer and fellow 34-year-old Chrysler engineer Gary Romberg, both from the Chrysler Race Car Engineering Group, were assigned the task in early 1968. Within 12 weeks they’d completed wind-tunnel testing and produced a new Daytona series ready for production.

The Romberg/Pointer team was an impressive matching of talents. Romberg was a Boeing-trained aeronautical engineer, Pointer a scientist specialising in physics. Their task was to change the face of the Charger radically without altering too much of the bodywork. In many ways the Daytona was a bandaid exercise, but in racing it’s winning alone that counts.

Their first ideas became wind-tunnel clay models, in both long- and short-nose versions. The long-nose version slipstreamed better but it also created unwanted lift. Romberg cleaned up this airflow problem by adding a chin spoiler to induce downforce and smooth out undercar turbulence.

Pointer, meanwhile, was working out the rear wing, which stood 23½ inches above the deck of the bootlid. It had a 58-inch-wide horizontal stabiliser that could be adjusted over 12 degrees. The base supports came off the top of the rear fenders, allowing the boot to open fully; the side supports acted as vertical stabilisers.

Just as the wind-tunnel studies were winding down, the first prototype was being rolled out of Creative Industries’ workshop. It didn’t take a lot of testing before the Daytona reached 200mph. As it blew past the timing tower the wind blast produced a different sound from the stock Charger – it sounded more like a jet aircraft.

The nose job and rear wing were only part of the story. The team added aerodynamic windscreen mouldings and a streamlined convex rear window perfectly matched to the rear body section.

The Daytona went on to blow Ford away. At its first showing on 14 September 1969 at Talladega, the Daytona pulled a scorching 195mph top speed. NASCAR promptly responded by demanding Dodge build 500 units to meet new class requirements.

While the Daytonas were knocking the spots off Ford, the Plymouth camp was in despair. ‘King’ Richard Petty had left at the beginning of the season as a result of internal wranglings at Plymouth Racing. Petty moved on to a year-long racing program with Ford but decided to return when Plymouth offered him the marque’s own winged warrior – the Superbird.

Plymouth realised the mistake of not attending that development meeting back in 1968. So it went to the same design team and persuaded it to begin an intense five-month development program.

Using its newly gained experience, the team refined the Daytona’s concept and results, producing a more sophisticated design using the Road Runner body, a new nose cone, larger alloy stabiliser surfaces and a pop-in convex rear window.

New wind-tunnel testing revealed that the vertical supports did a lot more than just support the wing. They acted as vertical stabilisers, contributed greatly to directional stability by moving the centre of pressure aft (the centre point is where the aerodynamic forces are known to act) thus reducing the vehicle’s tendency to yaw. In simpler terms, they acted like the tailplane of an aircraft, stabilising its movement through the air. The Superbird’s vertical panels were increased 40 percent to achieve maximum results.

Up front, the new steel nose cone was designed with an underbelly air intake for the radiator. This placed the intake directly in an area of high pressure, allowing for a massive increase in air flow to the cooling system. Below the air intake, a spoiler was employed to smooth out the air flow, reduce lift and overall drag.

Unlike the Daytona, which featured smooth leaded-in convex backlight windows, the Superbird was a hack job because of the limited time available to build the now-required 1954 homologation vehicles (one for every two Plymouth dealers) Plymouth figured the quickest way was to build the street cars by roughing-in the back window assemblies, not finishing them to paint quality, and then simply covering the roof with a padded vinyl top.

The job was done so roughly, all Plymouths display a marked depression revealing where the window insert and the roof section meet beneath the vinyl top. The conversion also required a new panel across the base of the rear window to meet the boot, along with mouldings across each lower corner to mould off the window.

The convex windows on both these wing cars were necessary as the original concave and recessed windows induced a positive lift in the rear section. This was a major factor in the stock-bodied cars’ high-speed instability.

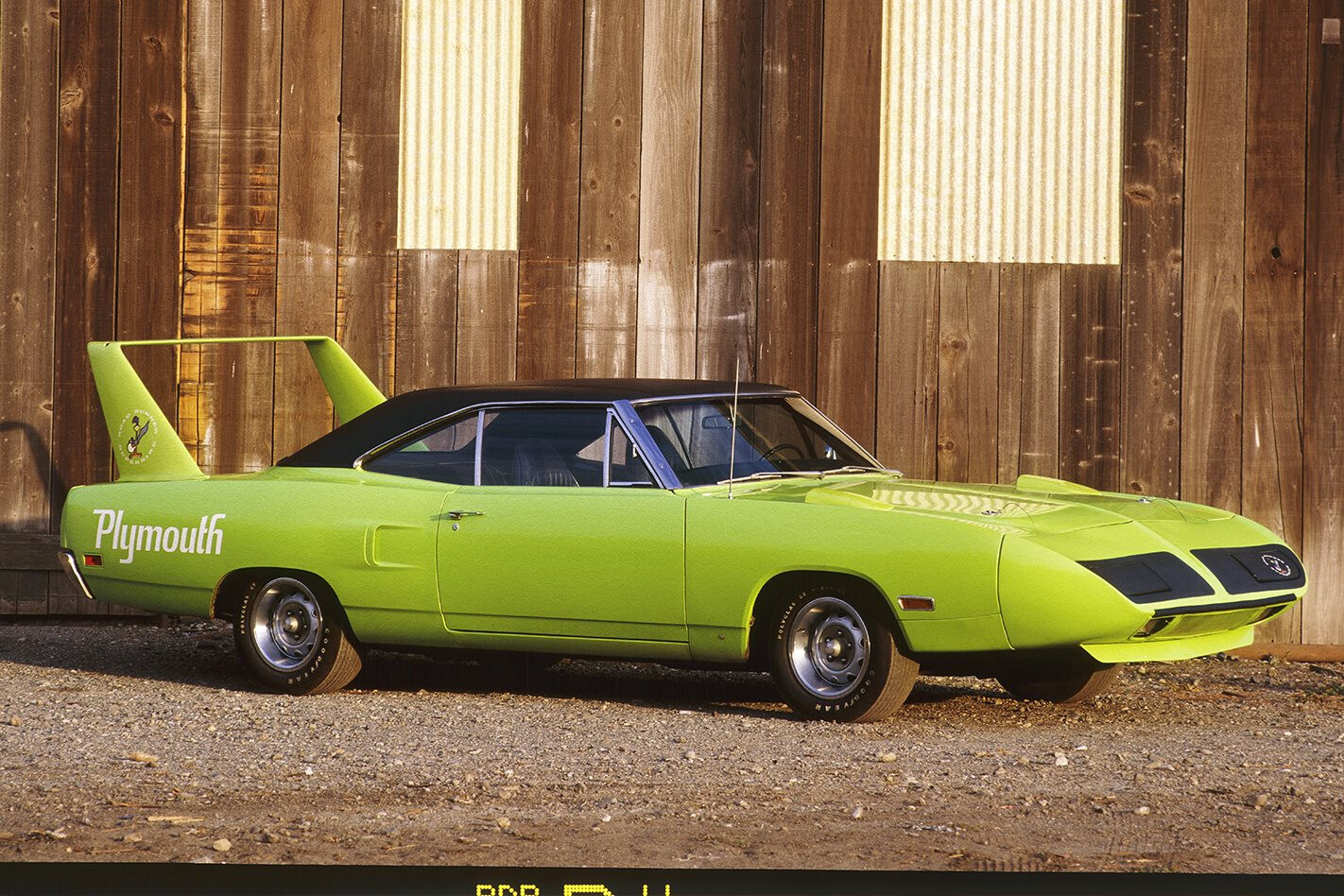

Other faulty details showed up in Bill Jurevich’s 1970 Hemi Superbird featured here. The huge Plymouth graphic running down each flank is perfectly applied on the left; on the right, however, the lettering was run into the side marker light and then cut to fit.

That’s only part of the story. The cars also came with 15×7-inch rally wheels capped with F-60 Polyglas tyres and extra-heavy-duty suspension. The ol’ grunt factor wasn’t missing either. The base motor was a four-barrel, 440 six-pack and the mighty Hemi 426 – bursting with 425hp!

Bill’s completely original Road Runner Hemi Superbird is a rare and expensive beast these days. Now highly sought after, Hemi wing cars have become the collectables.

Running a 10.25:1 compression ratio, the Hemi makes 425hp at 5000rpm. Carburation is through a pair of Carter ARB four-barrels on a trick Hemi manifold. It’s hooked up with a heavy-duty factory 727 Torqueflite transmission and an 8¾-inch Sure Grip rear axle.

Bill’s ’bird originally came out of Belmar, New York, but was sold by a Chrysler Plymouth dealer in Hillsboro, Oregon, in December 1970 for the all-up discount price of $3495 (sticker price was $5281). This included a list of 72 optional items, from rear armrests to six-way adjustable seats to bonnet pins, half horn ring, power steering and bucket seats. Bill’s Superbird is one of just 77 automatic versions built.

Detroit always had strong reasons for building its muscle-car image and the NASCAR title was more than enough encouragement. NASCAR, however, wasn’t too happy about how well the wing birds could fly – 220mph was way too fast for them. At the end of the 1970 season, Hemi 426-powered wing birds were banned. NASCAR claimed the Daytona/Superbird Hemi package gave Chrysler an unfair advantage and ruled that the wing birds’ engine capacity shouldn’t exceed 305 cubic inches. As a result, Chrysler was limited to a 5.0-litre V8 while all other manufacturers had unlimited power options up to seven litres. The Hemi was dead.

So 1970 was Chrysler’s swansong. Ford’s domination of NASCAR racing was over, winning just nine races that year while Mopars logged 38. The wing birds had taken the Grand National crown by a sweeping margin. Even NASCAR couldn’t take that away.

TECH

1970 Plymouth Hemi Superbird

Bill Jurevich

Featured: June 1991

Cool info: Plymouth made all the headlines it could from its short-lived Superbird, and that included colour choice: inside, you had the choice of black or white. Exterior paint, however, came in Lime Light, Vitamin C Orange, Tor-Red (think about it), Lemon Twist, Blue Fire Metallic and, um, Corporation Blue. All cars copped a black vinyl roof to cut down on the time needed to build the unique Plymouth

Paint: Lime Light

Engine: 426 Hemi

Carb: Twin Carter ARB four-barrel

Gearbox: 727 Torqueflite

Diff: 8¾-inch Sure Grip

Wheels: Rally

Comments