Blue Oval legend Big Al Turner has passed away at the age of 89. Turner’s contributions to motor racing history include his role as a father to both the modern funny car and the Ford Falcon GTHO.

To put his achievements into perfective we’ve reproduced Dave Fetherston’s profile on Big Al from 1995. Al’s journey from bucks down racer to gas turbine hybrid racing pioneer is quite the ride!

This feature was first published in the March 1995 issue of Street Machine

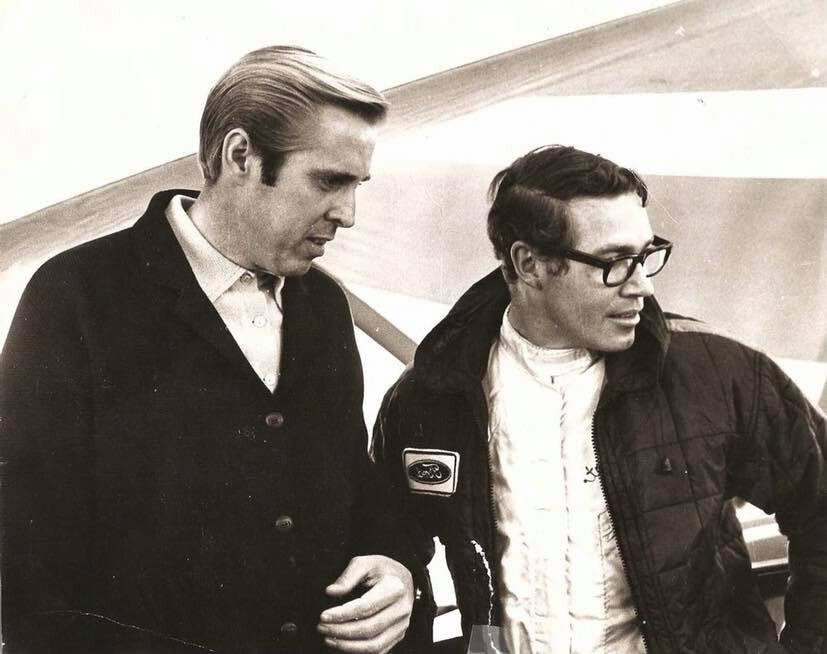

When Al Turner arrived at Ford Australia in December 1968, his presence was kept quiet for a while. The company was set on owninng the Bathurst 500 and the lanky import would draw on his years of dirt track dracing, drag racing, hot rodding and fabricating to accelerate the Falcon into the legendary Phase series.

He started racing as a young man in the US Army Engineering Corps, when a group of guys from his platoon ran a ’37 Ford coupe at local dirt track events.

Al and the boys had built a completely stock engine, but had the changed diff ratio to gain an edge. The car won five races in a row and was an early sign of how cunning Al could be.

In 1955 he joined the Ford Motor Company as a research engineering technician and spent time working with the fuel and lubricant boffins. In the lab and on the track, he played with fuels and blended his own brews, an art he never forgot. Al fast-tracked through Ford, changing jobs every 18 months to learn each production phase of an automobile.

On weekends, he went drag racing. Although a Ford engineer, Al raced a AA Gas dragster powered by a 283ci small block Chev that he had stretched to 400 cubes using a crank and piston set he’d manufactured.

Al won his class at the World Series of Drag Racing and dominated Detroit Dragway in 1958 and ’59. Five years later, Fran Hernandez, who headed motorsport at Lincoln/Mercury recruited Al to lead his new drag racing program.

The Comet 427 race cars were already underway when Al arrived. “We came out with the ’64 AF/X Comet and cleaned house at the 1964 NHRA Winternationals at Pomona, Al remembers.” For its time, it was an innovative car that drove straight and fast.”

During this time, Ford’s Special Vehicles Activities group had built several stretched nose, steel bodied ’66 Mustang fastbacks. These early funny cars featured injected 427 SOHC egines set back in the firewall, with the front axle mounted way ahead of the engine. The most famous of these was the Holman and Moody-built TASCA Ford ‘Mystery 9’ Mustang. It turned 9.73-seconds at 140mph.

When Hernandez asked Turner how Mercury could compete, Al suggeted they break out of the mould. At his drawing table, with slide rule in hand and 15 years racing experience to draw on, he conceived the first tube-framed funny car.

Hernandez gave the go-ahead to sign up the Logghe Brothers to build five tube-chassis, fiberglass-bodied Mercury funny cars in late ’65. Al gave the brothers an exacting chassis design, with the suspension layout and torsional rigidity factors he wanted built into the cars.

These cars were to become the first generation of the the modern flip-top funny car. Fitted with one-piece Mercury Comet bodies, three cars were build as fuel injected coupes, while a fourth car appeared as Jack Chrisman’s toplesss, supecharged nitro-powered roadster.

When it became apparent that four-speed manual transmissions were not optimal. Al had the Comets fitted with automatics and worked with Ron Logghe to develop the now-ubiquitous ratchet shifter. Within eight months, the cars improved by two-seconds and hit speeds of 200mph.

The Comets and their Ford derivitives dominated Unlimited Stock Eliminator for more than two years. At the ’67 Manufacturers Funny Car Championship. ‘Fast Eddie’ Schartman took the title in a Comet to the tune of 7.86-seconds.

Turner’s success with funny cars had been spectacular. Mercury had received massive press coverage and enlarged its market with the under-30s.

Al worked on other Mercury and Ford motorsports programs in mid-1967 through 1968. These included Trans Am and muscle car projects like the 428 Cobra Jet, Cougar GTE 428, Cyclone Spoiler, XR-7 Cougar Eliminator and the Cobra Jet Torino.

Aero tricks that Al had learned on the funny cars were transferred to Trans Am road racing and then to production cars like the Boss 302 Mustang.

This work included his design of the iconic ‘shaker’ scoop that made it onto both Ford and Mercury products – and was ultimately fitted to Aussie GT Falcons.

Al’s connection with Australia came about when Ford Chairman Semon ‘Bunkie’ Knudsen toured Australia in 1968. He felt a motorsports program could improve the company’s image with younger Australians and decided to send Al to Australia to create a highly-visible performance image for Aussie-built Fords.

Al took over from Harry Firth, who had been running Ford’s racing program. Al proposed importing a V8-powered Pinto to replace the Cortina and Falcon as a racing platform. This was rejected, but his next idea was a winner – to build a GTHO program, based on what had already been achieved with the GT Falcon.

Liking the idea of a coupe, Al and Ford chief stylist Jack Telnack turned out a two-door post concept car using XT Falcon front sheet metal, GT grille and Mustang wing for the Melbourne Motor Show. It was powered by a 427ci big block and topped off with Al’s trademark shaker scoop. It also featured wide-stripe GT graphics and Alan Jackson’s iconic Super Roo decal.

This was heady stuff for late 60s Australia, but Ford execs canned the coupe idea, so the four-door GT became the focus. Ford Oz had been sourcing parts from its motorsports programs in the US. Now, that Turner was on board, the flow of the good gear escalated. However, it was the tech that Tuner has stored in his head that was most important.

The 1968 Bathurst race had been a disaster for Ford. Seven Holden Monaro GTS 327s faced off against nine Falcon GTs. The Monaros romped home to a 1,2,3,4 place win.

The XW was due to replace the XT in mid 1969. Big Al acted quickly. The new XW GT was fitted with the 351 Windsor, producing 290hp and gave the GT a top end of 130mph. From this foundation, Al refined the GT for Bathurst. He tested fuel consumption, suspension set ups and tyre combos. Suspension changes were made and uprated the Windsor’s output. Ford released it as the GTHO.

It came with both Turner spoilers, a rear roll bar, three-inch tailshaft, high-lift cam and 650cfm Holley with aluminium manifold. It was still listed as 290hp but Al knew better to release any more details.

The front spoiler was said to give over 350lb downforce, counteracting high speed lift. “We found that it forced the air around the car, not under it where it produced drag, attached to all the rough edges,” says Al.

Tyre testing with Alan Moffat at the helm in two Sandown 500 races showed that Turner’s preferred Goodyears would last the distance. However, Moffat’s driving style was so fast and smooth that Al miscalculated the tyre wear for the other team drivers who were more heavy handed.

At Bathurst, Ford placed second in the hands of privateer Bruce McPhee after a series of tyre failures. “I took a lot of heat for that tyre deal,” Al recalled. “I made a judgement call which would have won the race under other circumstances.”

Around this time, Phil Irving was closing up his Repco-Brabham V8 program, with a staff of highly talented engine builders, machinists and technicians. Al picked a team.

“These guys were brilliant, hard working and fun to have as workers and friends,” he recalls. Without these guys, whe wouldn’t have achieved so much.”

August 1970, Ford announced the next step in Al’s plan, the GTHO Phase II. Gone was the Windsor, in its place the 351 Cleveland with 780cfm Holley, improved oiling and a 6100rpm redline.

In early 1971, the XY replaced the XW and Al built a series of race-ready XY GTHO Phase IIIs. These cars were rated at 300hp, but Al had turned on all his tricks to make sure the Falcons has a better-than-good chance at Bathurst.

“We designed a 36.4 gallon long-distance tank and optioned it in the car,” says Al. Suspension and aredynamics were further refined.

The crowning glory was the shaker scoop. “It was a cold-air, ram-type induction that helped us give extra power across the range,” Al tells me. “We tweaked the living daylights out of those engines. We were producing between 380-400hp in the Bathurst cars. We also had our redline set at 7300rpm, which gave us a 174mph top end.”

Bathurst 1971 vindicated Al’s work. The Falcons came home triumphant in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th and 12th.

By 1972, Howard Marsden had taken over, while Al moved to other projects. However, at Bathurst, things didn’t go to plan. The chin spoilers had been removed, which upset high speed stability and over-cooled the brakes.

Al had worked hard with Ferodo to develop a special brake compound which would operate perfectly in a specfic temp window. The removal of the spoiler lowered the brake temperatures and the brakes went bad in the first hour of racing.

“The whole team was race-ready, but others thought they knew better,” says Al. “The team engineers and mechanics kept telling Marsden not to mess with the spoilers or the brakes, but he wasn’t listening. It sure made for some fast learning.”

Al had built Ford its legend. When he arrived in Australia, Ford’s share of the market was 19.2 per cent, but the the time Al moved onto his new assignment, Ford’s market share had grown to 27 per cent.

Today, Al is a senior member of the Chrysler Corporation, with the title of Specialty Vehicle Program Executive. He oversees the development of the Viper and Prowler, as well as running Chrysler’s concept and show car program.

However, racing is not forgotten. Al is also the man in charge of Chrysler’s new hybrid/electric Patriot Le Mans in 1995.

Comments